Don Megerle’s office stands out, to say the least.

Tucked into a third-floor suite at 80 George St., Megerle’s office is a sensory overload: aside from the various decorations and string lights, hundreds of photos as well as certificates and honors, cover every inch of the walls both inside and outside the office.

Megerle started his career at Tufts as the men’s swimming coach in 1971, a position he held for over three decades before transitioning to become the director and coach of the Tufts University President’s Marathon Challenge in 2004. After 49 years as a Jumbo, Megerle’s life is up on his walls.

“I stuck around because I never thought that I wanted something better,” Megerle said. “I always felt that better is here ... Polish this a little better. Make this a little better. Make your office your home. And that’s what I’ve done.”

Megerle is not alone in his longevity in Tufts athletics. Four people currently employed by the university have been involved in athletics since the Daily began sports coverage in 1980.

John Casey (LA’80), currently the baseball head coach and associate director of athletics, played baseball and football as an undergraduate. He returned as an assistant coach a year after graduation before securing the head coaching position in 1984 and taking on an administrative role in 2001. Bill Gehling (A’74, AG’79) played men’s soccer as a student and coached women’s soccer from 1979 until he was promoted to director of athletics in 1999. He led the department as athletic director from 1999 to 2015 and now works in University Advancement as a senior advisor and interim executive director of alumni relations. Additionally, sailing coach Ken Legler has held his position since 1980, although sailing is not an NCAA sport.

Casey, Gehling and Megerle were quick to point out that athletics at Tufts have always been great. But through those more than 40 years, Tufts as an overall institution has changed reputationally.

“As the reputation grows and more people see Tufts as a great destination, that includes great athletes who are also great students,” Gehling said.

And alongside that growing reputation was a wealth of other factors — including a new restructuring of the NESCAC and NCAA, Title IX, administrative support, facilities improvements, fundraising and dedicated coaches — that together solidified the Jumbos’ top spot in athletics.

The ’70s, ’80s and ’90s: New opportunities

Under the leadership of Athletic Director Rocky Carzo, who served in that position from 1974 to 1999, Tufts navigated its way through a changing landscape of athletics through the 1980s and 1990s.

“[Carzo] got the ship going in the right direction in so many ways,” Casey said. “If you ever saw this place more than 40 years ago, you wouldn’t recognize it.”

Tufts had been a member of the NESCAC since 1971, but the conference was not as centralized as today. Individual schools used to make their own schedules — often with games against non-NESCAC Boston-area schools such as Boston University and Harvard University — and there were no conference standings or championships, according to Gehling.

Presidents of NESCAC schools saw athletics as important but wanted to keep them within their “proper bounds.” In other words, academics came first; athletics were an additional, but not crucial, part of the NESCAC experience.

“When I went to school, athletics at Tufts were across the tracks, both literally and figuratively,” Gehling said. “They were just kind of an afterthought. There were some great athletes and some great teams, but it really didn’t have much focus.”

But slowly the NESCAC, which was originally focused on football, grew and became a more solidified conference through the 1980s as administrators began to see the place of athletics programs as crucial extracurricular activities — a core guiding principle of the conference to this day.

“That’s an argument I’ve been making for a while,” Gehling said. “[Athletics are] part of the overall experience, and that’s not just athletics, it’s all the outside the classroom types of things that you care about … For the university to flourish, the university has to celebrate that and embrace that as part of the overall experience.”

Importantly, Title IX, which was passed in 1972, required institutions like Tufts to provide equitable opportunities for women’s sports. Prior to Title IX, Gehling explained that Carzo oversaw two separate athletics programs, one for Tufts College, the men’s school, and one for Jackson College, the women’s school. Many of the Title IX changes did not come until the late ’70s, when Gehling was first hired as women’s soccer coach.

Meanwhile, the NCAA three-division system, initially established in 1973, was gaining more traction nationwide, which began to stratify athletic talent and funding.

But, a NESCAC rule largely prohibited teams from competing in national championships until 1993, so most teams competed in the Eastern College Athletic Conference (ECAC) tournaments, if anything. Similarly, NESCAC tournaments did not exist for most sports until 2000.

To compare the 11 team national championships and 54 NESCAC championships that the Jumbos have won in recent years to seasons in the 1980s and say that athletics have exploded off the charts ignores the larger narrative.

“When you try to compare eras, everyone gets into trouble because it’s just not the same,” Casey said. “It’s tough to compare things that aren’t the same.”

Sports information and media were other important factors throughout the ’80s and ’90s that gave Tufts athletics more notoriety. Current Director of Athletics Communications Paul Sweeney was hired in 1993, replacing previous sports information directors, who — as Megerle put it eloquently — “didn’t know left from right.” With schedules, statistics and rosters publicly available, fans, other teams and, importantly, prospective students, began to recognize the success that had always been present at Tufts. The Daily’s coverage beginning in 1980, too, bolstered awareness of athletics, replacing the once-a-week Tufts Observer.

“The biggest thing, and I think the Daily gets credit for this, is that people have much more awareness about what these student athletes are doing,” Casey said. “And a lot of the stuff they do is pretty incredible.”

The 2000s: Presidential fans, new facilities

Increased support from former university presidents and current University President Anthony Monaco also spurred the growth of athletics in Jumboland.

“[University] President [John] DiBiaggio was the first president, if you ask me, to recognize the importance of athletics at Tufts,” Casey said. “He just knew that Tufts had it right in the perspective that it was part of the student experience — it wasn’t bigger, but it was important. He had come from Michigan State [University], so he had seen the other side of it being blown out of proportion.”

After DiBiaggio stepped down as president in 2001, Lawrence Bacow was hired as university president. While making himself a more accessible figure on campus, Bacow enthusiastically supported athletics.

“[Bacow] brought a breath of fresh air,” Megerle said. “He was very personable, he would go to the games, he would welcome people into his office. Wherever you went, Larry was there.”

Since Bacow stepped down in 2011, Monaco has continued the administration’s support of athletics. Monaco is often spotted cheering on the Jumbos at games and meets.

Mergele recalled the 2018 men’s swimming and diving NESCAC Championship at Bowdoin, when Monaco drove to Brunswick, Maine to surprise the team after following the results online.

“[Monaco] calls me up and says ‘It looks like the men are going to win the championship tonight. Let’s drive up to Bowdoin together,’” Megerle said. “Who would do that?”

The impact of the administration’s support has been tangible for student-athletes.

“One [women’s basketball] player said, ‘The coolest thing that I’ve had as an athlete at Tufts it to look up in the stands and see my president watching the game,’” Megerle said. “I mean that’s powerful stuff. The kids see that.”

And, the administration’s support has led to several facilities improvements, especially in the past 20 years. Under Gehling’s leadership as athletic director, new facilities were built, including Bello Field in 2004, Shoemaker Boathouse in 2006 and the Steve Tisch Sports and Fitness Center in 2012. While the improvements were funded by donors, they were spurred by suggestions of the athletics board of advisors and supported by the administration.

“Walking into the Tisch Center is such an awesome experience compared to what it was before,” Gehling said. “It was reflective of the fact that Tufts was recognizing the need that I don’t think was really recognized before.”

The fundraising that built these new facilities has gone hand-in-hand with the overall growing reputation of the school and the sports teams. Today, fundraising plays a significant role in developing athletics: last year, Giving Tuesday, for example, generated over $450,000.

“When I was coaching, we never had any of that stuff,” Megerle said. “If we needed money, we would talk to an alum who was doing well and had some affluence, and he’d send us a check for a few thousand dollars to get us through the season. But now, fundraising is a big deal.”

As teams got more opportunities to win on a national scale, publicity increased, as did fundraising and administrative support, so more alumni became involved, which in turn improved the athletic facilities.

“It was almost like critical mass, like a snowball rolling down a hill,” Gehling said. “All these things just came together.”

What makes them stick around

Both academically and athletically, Tufts has been a breeding ground of sorts for coaches who move on to Div. I schools. In the past year alone, men’s soccer coach Josh Shapiro left for Harvard and women’s basketball coach of 17 years Carla Berube left for Princeton.

“It’s rare that somebody at this level leaves because they aren’t doing well,” Megerle said. “They leave for something better.”

But there is a solid contingent of coaches who have dominated throughout the past 20 years, as Tufts has grown to become one of the top Div. III teams in the nation. Field hockey coach Tina Mattera, women’s soccer coach Martha Whiting (LA’93), men’s and women’s swimming and diving coach Adam Hoyt, men’s basketball coach Bob Sheldon, women’s track and field and cross country coach Kristen Morwick and volleyball coach Cora Thompson (LA’99, AG’01) have all built successful programs over their decade-spanning tenures as Jumbos.

“We very intentionally hired coaches who not only are terrific coaches, masters of the sport and all that, but they are really good team builders,” Gehling said. “They are really good at understanding why a place like Tufts invests in athletics.”

Now-retired coaches such as Branwen Smith-King, women’s track and field and cross country coach from 1982 to 2000 and assistant director of athletics from 2000 to 2017, and Nancy Bigelow, women’s swimming and diving head coach from 1982 to 2015, also defined greatness in the past 40 years of Tufts athletics.

“For all that she was a soft-spoken gal, she had some great athletes,” Megerle said about Smith-King.

Something in the Jumbo culture evidently keeps these coaches around for a long time, which other schools can struggle with. For Casey, it has been the value placed on individuals.

“My feeling about this place from day one was that it was always about people,” Casey said. “I think there are a lot of institutions that are about the institution, and not necessarily about people. That’s always been Tufts’ strong point.”

Looking back at more than four decades, it is hard for people like Gehling not to get a little sentimental.

“You look back and you realize what kind of an impact this whole endeavor has had on the students and on [us],” Gehling said. “It’s been a wonderful ride.”

Looking back on 4 decades of Tufts athletics

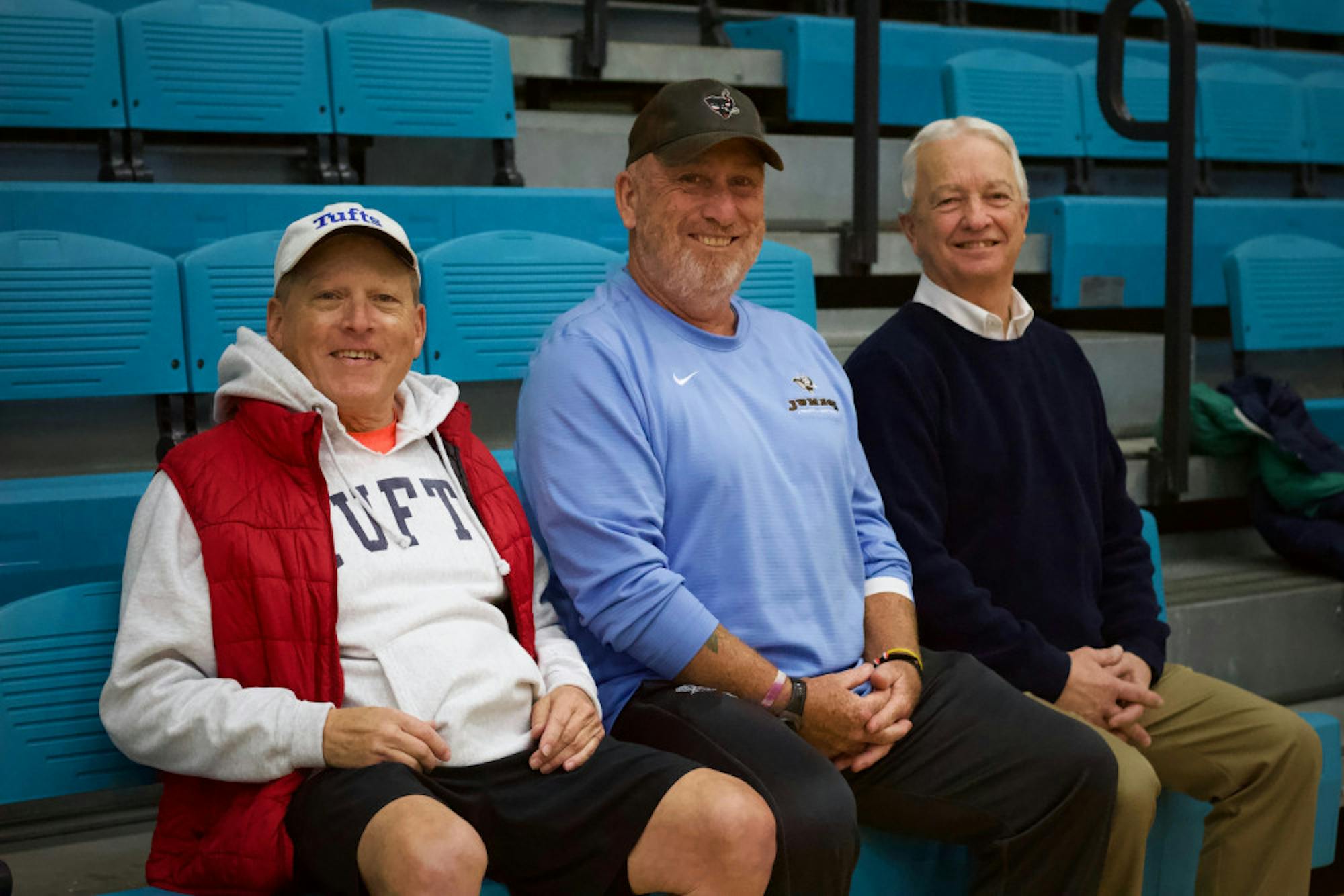

Don Mergele, John Casey and Bill Gehling pose for a portrait in Cousens Gymnasium on Feb. 20.