The call came in the middle of the night. In that hour when both professors and the sun have long retired to their chambers, the playful minds of the students were stuck in overdrive, furiously shifting mental gears from fast to faster as the darkness provided a starry blanket for mischief. The phone call awoke Rocco Carzo — then−athletic director — from a deep slumber at 2 a.m., as he jerked out of his bed to the shrill ringing piercing his ears.

On the other line was a Tufts University police officer, who fumbled with his words before getting out the news. He had caught members of the 1982 women's lacrosse team on top of the field house, an old World War I barrack transported to Tufts for athletic use, outside of the Ellis Oval. Was the charge marijuana smoking? Alcohol abuse? Neither. The Jumbos had shimmied up the side and spray−painted an ode to the team on the roof, decorating the building that once housed America's finest with a barrage of white paint to salute the squad on the eve of its biggest game of the year.

It was a chemical reaction more commonly seen in a lab, a perfect fusion of sport and spirit that bubbled over in a fury of paint brushes and buckets atop a rickety roof. More importantly, on that late morning in 1982, the pride of the Tufts women's lacrosse team was on display for the world to see.

Carzo excused the Jumbos to the police officer, saying he had given the players permission to do the painting, and the team was let go. But the memory of the moment lives on in an aerial photo taken the next day. In the left−hand corner of the photo sits the roof of the field house, emblazoned with white streaks of "Jumbo pride," "No one does it better" and "Never underestimate the power of a Jumbo."

On a near−silent campus, the Jumbos were being, well, Jumbos: a boisterous bunch of athletes bent on letting their school know who they were. And while years later Tufts University buildings remain relatively defacement−free, the tradition of the women's lacrosse team has lived on. The spirit is born

Rewind the clock back seven years from this event to 1975. "Wheel of Fortune" had premiered, an assassination attempt was made on President Gerald Ford, and the world's first home computer was released onto the market. But most importantly, in the year dubbed International Women's Year by the United Nations, the women's lacrosse program at Tufts was elevated to varsity status three years after the initiation of Title IX.

Hop in the time machine and speed ahead to 1980. Marisa Didio, fresh off of graduation from the University of New Hampshire, arrived at Tufts. As a 21−year−old faced with the daunting task of controlling and molding players her own age as the head coach of the women's lacrosse program, Didio channeled her passion and dedication into an immediate pay−off for a young Jumbos unit. In her first year, Tufts went 9−3−1 behind 47 goals from all−time leading scorer Jenny Payette (E '82).

The rest is history.

That's not to say that the Jumbos did not have success in their first few years before Didio came on as coach. Far from it, in fact. Under coach Mary Sturtevant, Tufts went a respectable 24−13−5, but Sturtevant left the program after going 5−5−1 in 1979 — one of just four times in history that the team has posted a .500 record. An administrator and a high school teacher, Sturtevant was faced with demanding responsibilities outside the world of Tufts athletics, so when she left, Carzo went searching for a replacement who could bring more attention to the athletes.

Cue coach Didio, who rode onto the Hill with a sweeping wave of enthusiasm, instantly gelling with both her players and the athletics department as the program began to slowly take shape.

Twenty−seven wins, 11 losses, two ties in three years. A winning percentage of .700, second−best in program history. The relevant facts, though, do not show up in the statistics in box scores and charts: off−the−wall intensity, a heightened sense of fun and extensive progression. If those could be measured in decimals and percentages, Didio would undoubtedly be one of the all−time greats.

"First of all, she brought Marisa," Carzo said. "She came as she was. And the beauty of her was that she didn't try to be anyone else; she was authentic in terms of what was important to her. And not only was she unique, but she retained whatever it was that she came with, her background and coaching all stayed the same. There was nothing that was adjusted or changed to meet anybody's whims … And it went from average to good in a big hurry."

Recognizing that the key to success within the program was to minimize mistakes, especially in an age when women had limited access to facilities, Didio's learn−by−doing mantra brought drastic changes to the women's work ethic.

"She was a very intense coach, very focused, completely professional," said Kate Donovan (J '84), who played under Didio for three years. "She was good and motivating. Not that anyone playing in college needs encouragement to want to win. Everyone wanted to win and was motivated, but she pushed you to excel. And I don't know how she did that, but I guess that's what makes a good coach."

"The ironic part about it was that I thought these kids were going to get their asses rattled with Marisa, because she came from a tough program," Carzo said. "But it was the opposite. They lauded on her; they just loved her because she was respecting them by working them hard and disciplining them to the extent that they were disciplined. They were undisciplined before; I remember a kid saying that if they wanted to go to get haircuts, they would just go; the coach didn't care." Unhinging doors with attitude, passion and intensity

Even today, as she heads a private field hockey coaching camp in New Hampshire, Didio's values remain the same.

"You have to win," she said, emphasizing that she doesn't preach passion but instead brings an intense personality to the field. "[My players'] whole motto was ‘you gotta believe.' I still go back to that years and years later because the reason those kids won championships was because they had that belief."

Led by Payette, whom former Daily writer Renee Gerard once compared to Wayne Gretzky and described as the top woman athlete at Tufts in a March 24, 1982 article, the Jumbos scored a New England College Women's Lacrosse Association title on their home field in 1982 in a 7−6 squeaker over Trinity, the night after the players adorned the field house with their quick−dry kookiness.

"That was their passion; that was their vibrato, their way of showing how spirited they were," said Didio, fondly remembering being hoisted up in the air with the trophy following the game. "They lived life, and they were going to get the absolute most fun and opportunity out of the experience they had in those four years. They had a love for it. It was amazing."

Even today, as the Jumbos have dispersed across the country, the memory of that night on the roof has stuck with them.

"It was like we put the team before everything, including school," Donovan said. "It was everything for the team. Everyone just put everything into it, heart and soul. You can't describe it."

In an age when NESCAC teams were banned from participating in NCAA−sanctioned national tournaments — the conference founders deemed it inconsistent with the league's message of an academics−first experience — the ludicrously talented squads of the early 1980s would almost certainly have challenged for the ultimate trophy.

Regardless of what stands in the display cases at the Athletics Department, however, the culture Didio created within the women's lacrosse program spread throughout the campus, invigorating interest in women's athletics from the students to the administration.

"One of the purposes of athletics is to be a rallying point … for the rest of the community," Carzo said. "And prior to her coming here, you never saw anyone at a women's lacrosse game or at a women's anything game. But Betty Mayer, the [university] president's wife, would come down and watch practice all by herself, just to see how the girls were doing. It impressed her that they worked so hard, and she wanted them to know that they would care. She never went to a football game, but she went to support the women because they were doing a great job."

And by the time Didio departed in 1982 to return to a coaching position at her alma mater, her four years of strong recruiting classes set the stage for later success.

"She, as a coach and as a person, absolutely strives for excellence in everything, in practice, nevermind in games," said Donovan, now a special agent in Boston with the U.S. government. "And she was a disciplinarian, too; make you run two miles if you were out of line. But there was huge pride in saying ‘I play lacrosse for Tufts.' And I think she started that, and that carried on."

More immeasurable was the spirit embodied by Didio, seen even after the moment she left. On her office door at Jackson Gym were pictures and articles about the team. When Didio left for New Hampshire, Donovan unhinged the door and put it in front of her former coach's new office.

"I would be thankful for that, complimented by that, but I know it boils down to so much more than that: It boils down to the kids," said Didio, when asked how she would respond to statements that she turned the program around. "It was an unbelievable culture of support, relative to athletes supporting other athletes, not just emotionally but by live participation in each other's events. It was so unique." The lasting impact

Over the ensuing four years, the Jumbos endured three coaching changes, all the while maintaining the same winning mentality instilled in the earlier part of the decade. Under coach Diane Sorrenti in 1983 and Nita Lamborghini in 1984, Trinity eliminated Tufts in the Northeast Intercollegiate Athletic Conference Tournament by 15−1 and 14−11 margins, respectively.

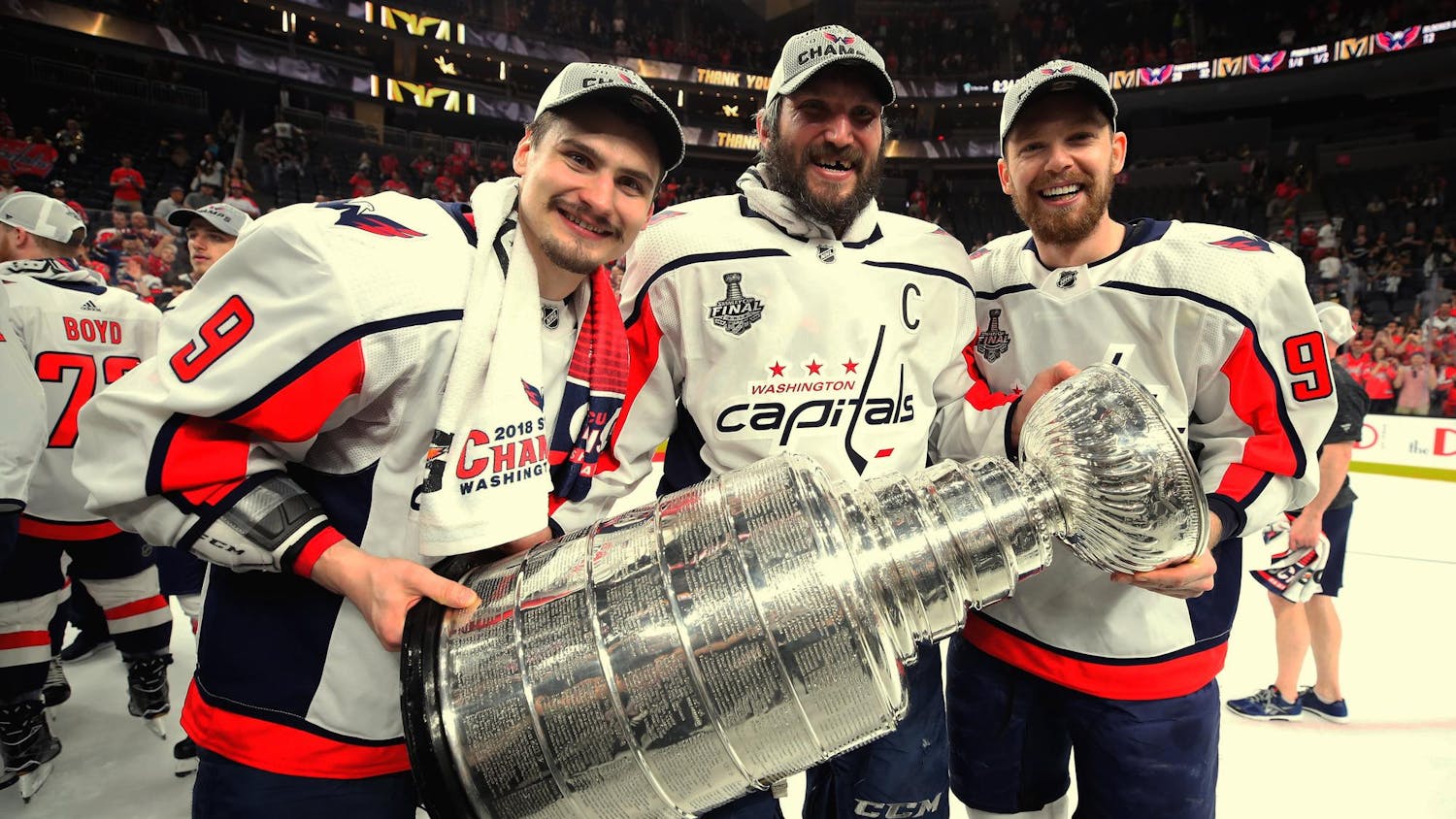

The strain of so many alterations to the head coaching slot ultimately subsided in dominating fashion. In 1985 under Lamborghini, behind a high−powered offense that failed to score fewer than 12 goals in a game only once, the Jumbos surged to the ECAC Championship and finished at an unblemished 13−0.

Sure, the Jumbos had the talent that shows up on paper — twins Nancy Winters and Lisa Lax (both née Stern, J '86) directed the offense with Donovan — but the energetic confidence that the players had as they strutted around campus, utterly proud to be part of the team, far outweighs the record.

"We were all proud to be Jumbos, and we weren't even shy about it," said Winters, who currently works with her sister as a film and TV producer at their co−owned Lookalike Productions. "It means a great deal to us, not just to win and to play well, but to play hard and to represent Tufts in the best way we possibly could. It was just one of those very synchronistic moments where all of us wanted the same thing."

With pre−game dinners on Friday night that all of the players attended, regardless of other obligations, the spirit gradually moved itself to the field. In warm−ups, the squad made a mix tape with such hits as Michael Jackson's "Beat It" (1982) and Kermit the Frog's rendition of "Rainbow Connection" (1979). It only seemed natural, then, to name plays after these pump−up songs. "Beat It," for instance, was a give−and−go between Donovan and the rest of the squad that, as Winters said, "almost always resulted in a goal."

And yes, they still continued to paint the field house roof.

"It was all about spirit and the heart of the game and our friendships," Winters said. "We played tournaments down in Virginia, and they all knew when the Jumbos were hitting the field. We were Jumbos, and we wanted everyone to know that."

But as Lamborghini departed, deeming it the time right to move on to Harvard to take charge of a Div. I program, a young coach from Colgate assumed the vacant position, beginning the modern age of Tufts women's lacrosse.

Fresh off of a five−year stint at the upstate New York position, Carol Rappoli entered in 1986 with the gaudy task of continuing the tradition of a program coming off its most successful year in history. And Rappoli, who competed against Didio when she was attending Wellesley College, delivered in spades.

In Rappoli's first year as head coach, Tufts obliterated Bridgewater State in the ECAC final, winning 24−5 to finish 11−1 overall, coming within just one goal in a 9−8 loss to Bowdoin of an undefeated season. Carrying on the proud tradition of fun through sport, Rappoli helped continue Tufts' ascent into a national powerhouse.

"There was no one in those years who could even come close to competing with those kids; they were way ahead of their time," Rappoli said. "When you start to win, it kind of just snowballs, and for four or five years, that's what happened. The kids that did come in were equally as good as those who had just graduated. I don't have any scientific reasons for it." ‘An evolution, not a revolution'

When Rappoli came to Tufts, she fell into a storied tradition, picking up right after her predecessors and proudly steaming ahead with the Stern twins as captain. From 1985−1989, the Jumbos went an absurd 61−2, including back−to−back undefeated seasons, the only two losses coming in one−goal losses to Bowdoin. In the decade alone, the Jumbos went 106−19−2, by far the best 10 years ever in Tufts women's lacrosse.

"Everything was in place," Rappoli said. "They had an absolute ball during the whole process. For those kids, it was definitely the best part of their day to go to lacrosse practice and play."

Likening the program's success to a snowball gradually rolling down a hill, picking up steam as it grows in both circumference and speed, Rappoli's job was made easy by the tradition and history of the program.

"Probably the number one thing that comes to mind is the kids work incredibly hard, in their studies and on the field," Rappoli said. "When I come to practice I don't have to tell them to work hard today, because that's a given. They work hard, and it shows in their passion in their play."

"We always have a positive attitude; it's always upbeat," senior co−captain Alyssa Kopp added. "It's more about having fun and improving while also being able to be competitive in a tough league. [Rappoli is] good at making practices light−hearted, but she also helps bring out our competitive nature and our winning spirit. She fosters a good team dynamic and never loses sight of the fact that we are a team and that we need to play together."

In trusting her players, Rappoli successfully fostered a dynamic of immeasurably strong team unity. On the wall in her office is a simple piece of construction paper, emblazoned with the phrase "Together" adjacent to a team picture.

"I think that I give a lot of responsibility to the captains, and the strength of our group is the strength of our captains," Rappoli said. "My job is to mind the ship and when it's tilting, try to bring it back to level. My role is to be a guide and teach them to play the game the right way, but it's not to develop their unity and things like that. I feel like that's part of their leadership in their evolution."

Perhaps Carzo put it best when he definitively stated that the Jumbos' success is the result of "an evolution, not a revolution." Despite a mere one−letter difference, the latter implies a spur−of−the−moment event, drastically altering the scope of something in one sweeping change. The former, on the other hand, infers gradualism, progressively but slowly getting more different over time. Taking Tufts lacrosse into the 21st century

The monotonous 1990s, like the product of a garbage compactor, can be crushed, molded and broken down into one efficient square of winning. There were no late−night calls, no roof−top paintings — just pure, unadulterated success.

The Jumbos missed just one ECAC Tournament in the 1990s, winning the New England Championship in 1995. The 21st century brought more of the same, as Tufts has made six NESCAC Tournaments in the oughts.

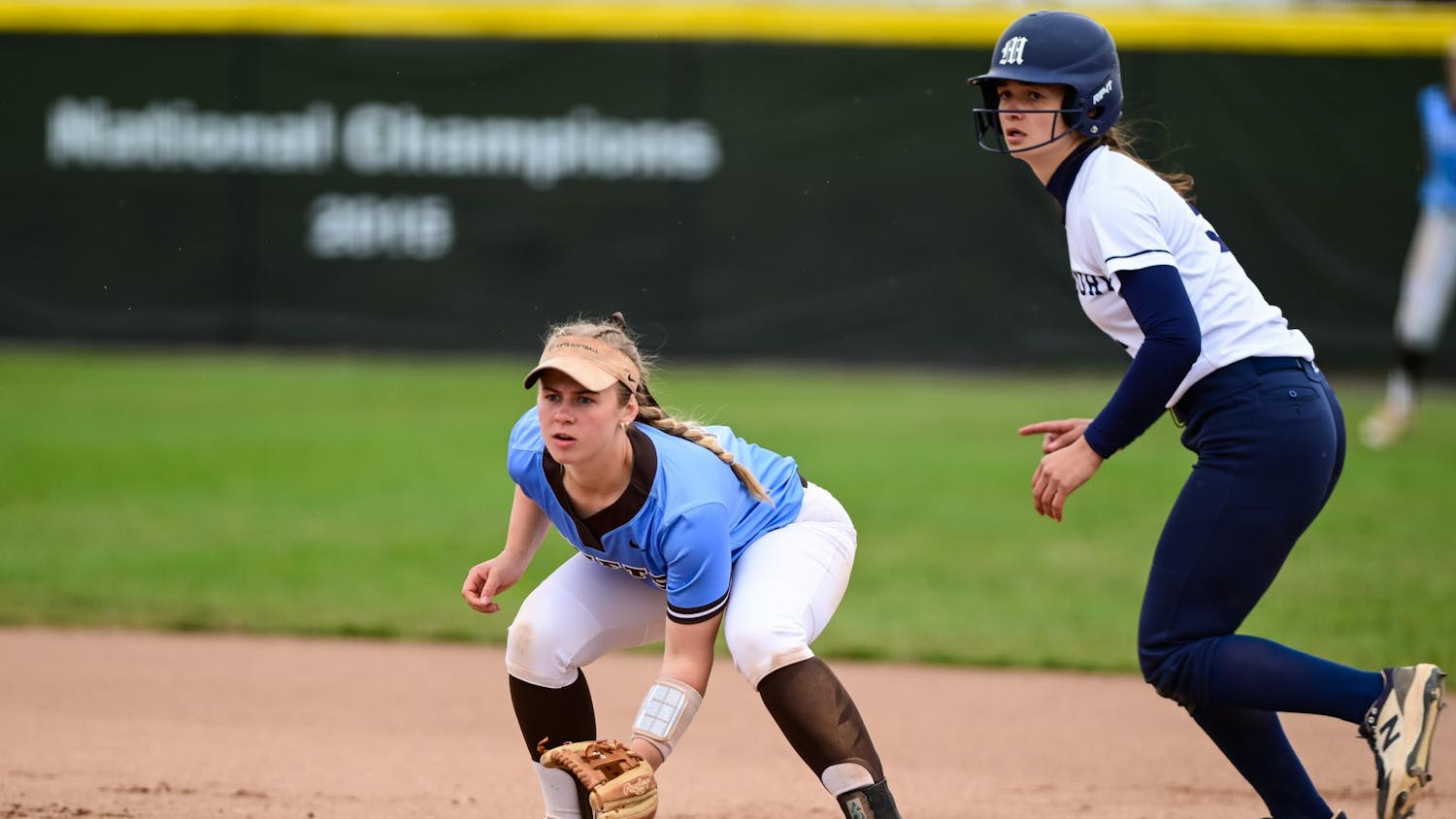

In her 24th year at the helm, Rappoli has accumulated a 226−102−1 record, including a program−best 16−3 mark last season in which the Jumbos made the NCAA Tournament for the first time in history. The turning point, in recent years, came two years ago when Tufts destroyed Middlebury on April 26, 2008, the long−time national powerhouse and bully of the NESCAC, 15−7.

"It changed the league," Rappoli said. "Middlebury was supposed to be up on this pedestal. It was a complete thrashing of probably the best team in Div. III lacrosse. Since then, I think the program has shot forward."

Even before that game, the Jumbos had experienced the success long indicative of the Brown and Blue, but defeating the Panthers rejuvenated a new swath of confidence within the players, perhaps renewing the carefree swagger seen in the early 1980s.

"I always knew they could do it, but they never believed that could do it until that year," Rappoli said. "Those seniors really pumped it into the kids that yes, you really can compete with that team, and they're no better than you are. They just wear a different color uniform. Last year, after finishing first in the league, it was like ‘Oh my God, we can do this again.'"

The field house has since been replaced, the slogans long gone from Tufts' campus. The spirit of women's lacrosse, though, shows no signs of destruction. And as the Jumbos head into the 2010 season searching for their second straight NCAA berth, they will do it with the same energy seen in 1982, albeit on a different, more elevated stage.

"I think it can only get better from here," Kopp said. "I think in continuing the philosophy of working together as well as knowing we can do well, we can definitely continue to be in the top 10 in the NCAAs if not win a national championship."

Because remember, it's an evolution, not a revolution.