Henrietta Lacks died of cancer in 1951 at age 31, not knowing that her cells would create the foundation for modern-day medicine and that her treatment would play a predominant role in the rise of medical ethics. During a hospital visit, doctors collected a tissue sample from Lacks without her consent. Biotech companies later went on to tremendously profit from Lacks’ cells without ever compensating her or her family. Sadly, this is one of many instances of blatant racism in the medical system, many of which do not receive nearly as much media attention.

Lacks went to Johns Hopkins Hospital for symptoms of abnormal vaginal bleeding. She was diagnosed and began treatment for cervical cancer. During that first treatment, her doctor extracted a tissue sample from her tumor and tried culturing the tissue like he had for other patients with cervical cancer. However, unlike other patients' cells, Lacks’ tumor cells remained alive outside of her body.

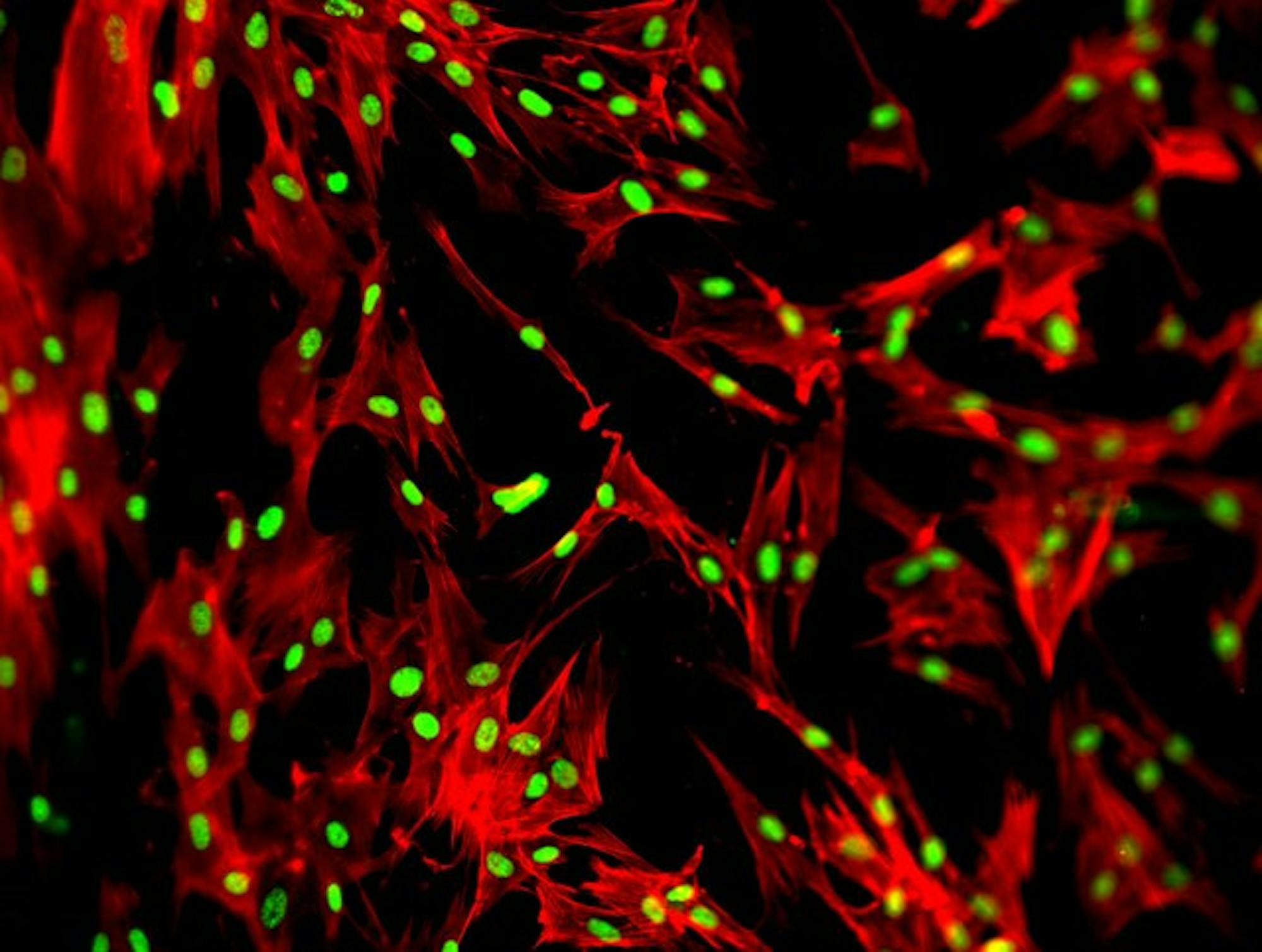

The tumor cells biopsied from Henrietta Lacks’ tumor were eventually called HeLa cells, following the common naming scheme of the first two letters of the patient’s first and last name. Before HeLa cells, cell lines would die soon after being removed from the body; however, these cells not only seemed to survive outside the body, but they would rapidly grow and double in population every day.

HeLa cells are called an immortal cell line because they divide an infinite number of times due to genetic mutations. Regular cells can only divide a finite number of times before they die. Immortal cell lines are often derived from tumors. For cancer cells to grow and divide as rapidly as they do, there are often mutations in genes that control cell growth. It’s these mutations that can lead to immortal cell lines.

Since HeLa cells were the first cells to be grown in a lab, they have been instrumental in many scientific advancements, beyond studying cancer. There have been over 11,000 scientific papers using HeLa cells, and scientists have won three Nobel Prizes with HeLa cell research. HeLa cells were also used to develop polio and COVID-19 vaccines, stained to enable counting of chromosomes, sent to outer space to help understand how radiation affects human cells and used to study AIDS.

HeLa cells were successfully cultured while Lacks was still alive, but Lacks and her family were not asked beforehand nor informed that the sample had been taken. In the 1950s, hospitals and doctors were not required to tell patients when they were taking samples because samples taken during diagnosing or treating diseases were seen as hospital property.

This was changed in 1991 with the Common Rule, a law that requires informed consent. This means that patients must be informed of the risks, benefits and goals of services provided by a doctor. Another aspect of informed consent is that if samples or even details from a patient’s case are used for research purposes, patients must be informed and can choose to not participate.

While the scientists who first cultured HeLa cells wanted them to be available for free because of its potential scientific advancements, biotech companies have profited off these cells for decades while the Lacks family has struggled to receive adequate medical care. The Lacks family were only told the sample had been taken when scientists approached the rest of the family to take blood samples for further research. Scientists continued to not ask the family permission before revealing Henrietta Lacks’ name or medical history. They even published her genome online, although it was later removed due to public outcry.

The Lacks family has been trying to get compensation from biotech companies who profit off HeLa cells. In 2021, the Lacks family sued Thermo Fisher Scientific, a major biotech company that mass produces and sells HeLa cells. The family demanded $9.9 million dollars and proposed that future uses of HeLa cells be approved by the Lacks estate. There are many biotech companies who profit off HeLa cells, and the Lacks family lawyers have suggested that these companies may be the next targets of litigation.

Currently, the case against Thermo Fisher is still being argued in the Federal District Court of Maryland, and no other cases have been brought, meaning the Lacks family has yet to receive any compensation.

In 2013, the National Institute of Health reached an agreement with the Lacks family that limited the use and publication of the genome of HeLa cells. Once scientists sequenced the entire genome of the cells, it revealed disease risks that Lack’s descendants might still carry. The agreement the Lacks family has with the NIH says for scientists to get access to HeLa cells genome for their research, they must show they have a need for the data, limit who has access to the genome and provide yearly updates on their research.

Another part of the agreement includes the Lacks family being further involved in the process of vetting applications for use of Henrietta’s genome. In turn, the agreements elude the matter of monetary compensation for the family and instead remain policy-focused.

This story highlights racial and socioeconomic inequality in health care and unethical research practices. A poor Black woman had bodily samples unknowingly taken from her, and those cells were instrumental to modern medical knowledge. Yet, the Lacks family struggles to receive medical care and still has not been compensated for the use of HeLa cells.