Imagine if we could curate the ‘perfect’ human being — from changing their eye color to developing resistance against deadly illnesses. Is this a groundbreaking pursuit or an unethical idea? When He Jiankui, a Chinese scientist, announced in 2018 that he had changed the genetic makeup of three babies to make them resistant to HIV, he was placed in prison for three years. Nevertheless, the influence of his actions on the scientific field is strong and persistent.

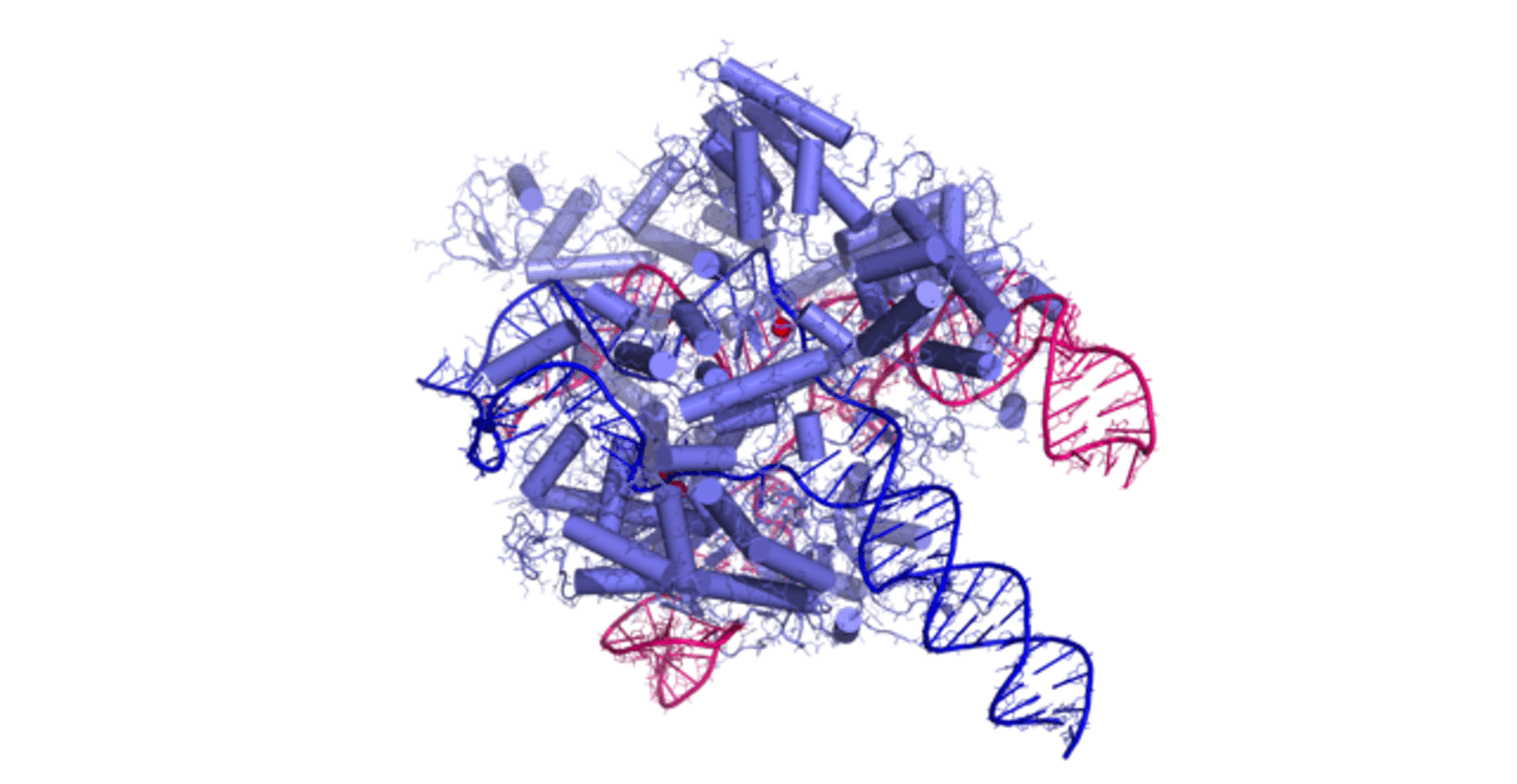

CRISPR genome editing was first introduced in 2012 by Jennifer Doudna of University of California, Berkeley and Emmanuelle Charpentier of the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in Berlin. They invented CRISPR-Cas9, a technology that can cut a DNA sequence at a specific site and either delete or insert other DNA sequences. In the future, this invention has the potential to allow scientists to alter not only a person’s physical traits but also their predisposition to diseases. For example, scientists are now looking to use genome editing to treat sickle cell anemia, caused by a gene mutation that disrupts hemoglobin production. Muscular dystrophy, cancer, diabetes and hereditary blindness are other examples of diseases that could be treated using genome editing, scientists hope.

Genome editing has the potential to go beyond solely treating genetic disorders. There is potential for developing technology to protect people against chemical warfare by modifying liver enzymes to make human systems better able to rid the body of toxins, Professor Robin Lovell-Badge, the organizer of an international summit on human genome editing, told the Guardian. Or perhaps, it could be used to help humans see in the infrared or ultraviolet range — a useful tool for troops fighting at night, Lovell-Badge said.

Despite the advantages of genome editing, there are also ethical drawbacks to be carefully considered before the scientific field begins promoting its widespread use.

For instance, genome editing for one person could cost nearly $1 million. Many people who suffer from various illnesses, like anemia, cannot afford expensive medicines. By implementing genome editing, are we creating even greater barriers to health care access?

The long-term implications of genome editing remain unknown, raising questions about complications that could arise like off-target DNA damage. The nuances of genome editing demonstrate the need for careful scientific study and consideration before implementing such large-scale scientific advances as potential treatments despite how appealing it may seem upfront.