A surge of new artificial intelligence tools is stirring concern among some faculty while others embrace it as university administrators move to address the new reality marked by chatbots capable of spitting out code and writing assignments in mere minutes.

The emergence of so-called generative AI, exemplified by OpenAI’s ChatGPT, has spurred some instructors to modify their syllabi this semester to defend against cheating. Others, however, see the sudden popularity of human-like chatbots as an opportunity to rethink their pedagogy and engage students in a fresh way.

“I think with these technologies, like others, there’s opportunities to use them productively, and there’s also opportunities to short-circuit learning designs,” Milo Koretsky, a professor in the Department of Education and the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, said. Koretsky studies engineering education with a focus on engagement and the development of disciplinary practices in the college classroom.

Koretsky has yet to play around with ChatGPT, but he said he imagines one way to use it would involve querying the program before having students critically analyze its response. The tool’s near-mastery of declarative knowledge — like facts that students memorize — could prompt educators to shift away from educational models that emphasize rote memorization, Koretsky said.

“Whenever you have a situation where you set up rules that people benefit from breaking — that’s a delicate system,” he said. “So in one sense, these technologies like ChatGPT might provoke a crisis within the education system, which leaves us to reconsider how things are taught.”

University administrators are in conversation with faculty about how to navigate the issues of academic integrity that come into play with ChatGPT, according to an emailed statement from James Glaser, dean of the School of Arts and Sciences, and Kyongbum Lee, dean of the School of Engineering. The duo anticipates they will “potentially” construct formal recommendations on generative AI’s use and will consider updating the academic integrity tutorial new students are required to complete each year.

“These tools have lots of promise and create new possibilities for learning and teaching, but they also raise important questions, including whether there are any implications for academic integrity,” Glaser and Lee wrote in their statement.

In certain courses, ChatGPT is banned entirely for assignments. An example is the introductory computer science class, CS11, which considers “lifting partial or complete solutions from anyone,” including online sources, to be in violation of the standards of academic honesty, according to the online syllabus. While the syllabus makes no direct reference to ChatGPT, it instructs students not to search the internet “about assignment-specific code or strategies.”

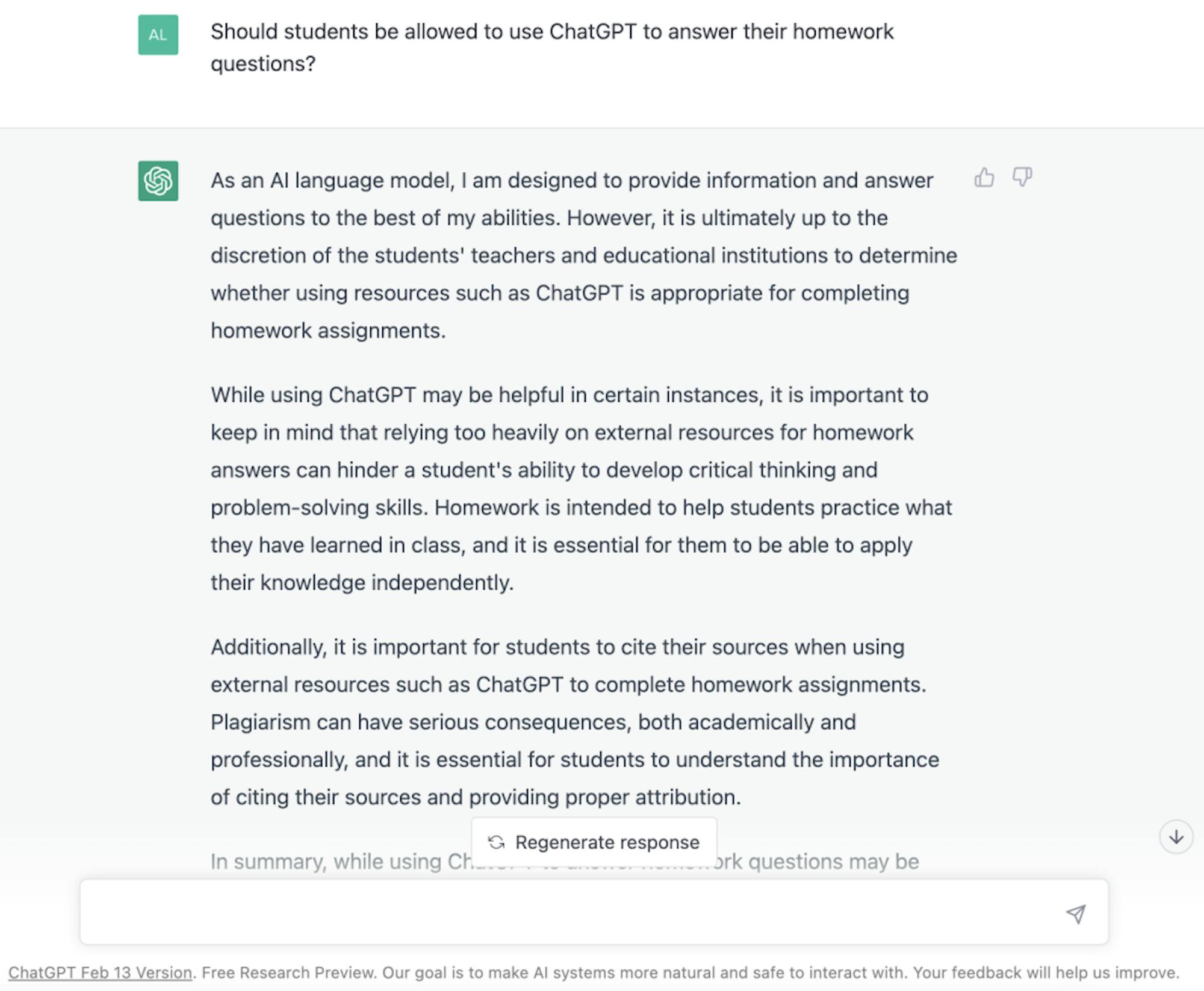

ChatGPT can solve portions of traditional CS11 homework assignments in seconds. The Daily sat down with a former CS11 student who pulled up the class’ homework assignments from fall 2022 and input them to ChatGPT.

One homework problem, for example, asked students to write a program that could identify and list, in descending order, the three largest numbers, given a file with a list of values. In less than a minute, ChatGPT responded to the prompt and assembled a program that worked, according to the student, who requested not to be named.

While the program used notation prohibited in CS11, the student was able to quickly rearrange the code into a submission that they believed could receive full credit.

Megan Monroe, the CS11 instructor, and Jackson Parsells, a teaching fellow for the course, did not respond to requests for comment. Neither did Jeffrey Foster, the department chair.

CS11 will administer an in-person final exam this semester, according to the syllabus, in a departure from last semester’s exam, which was scheduled to take place virtually even before reported bomb threats in December sent all assessments online. The move seems to follow a popular remedy used to mitigate plagiarism: handwritten work. It is unclear exactly why the CS11 exam’s modality was shifted.

On the other end of campus, the English department has grown concerned over tools like ChatGPT and their abilities to compose essays, generate ideas and pull information together from the farthest corners of the internet.

Sonia Hofkosh, chair of the Department of English, wrote in an email to the Daily that her department has not yet adopted an official policy regarding the use of generative AI, but plans are in motion to draft a policy soon. Hofkosh also said she plans to meet with the academic resource center and the Center for the Enhancement of Learning and Teaching to discuss ChatGPT’s use in the classroom.

For now, Hofkosh said, using ChatGPT to write an English essay without the instructor’s permission would be considered plagiarism.

Other courses are taking a different approach to the new artificial intelligence tools. Erica Kemmerling, a professor in the mechanical engineering department, adopted a policy that encourages her students to explore ChatGPT and employ it as a helping tool. Students in both of her classes are permitted to use the AI chatbot “without limits” for any assignment other than a quiz or exam, according to Kemmerling’s AI policy, which she shared with the Daily.

However, students who opt to use AI help must also submit a record of their interactions with the chatbot in addition to the assignments themselves. Kemmerling incentivizes her students to follow the rule by offering a bonus point for each conversation submitted alongside the homework.

Back in the computer science department, Ming Chow, who teaches Introduction to Security, is another proponent of ChatGPT. He not only permits but expects his students to use artificial intelligence, according to Chow’s AI policy, which states that some assignments will even require its use.

“Learning to use AI is an emerging skill,” reads the policy, which Chow said he adopted from Wharton School professor Ethan Mollick. “I am happy to meet and help with these tools during office hours or after class.”

Although ChatGPT has been reported to have done everything from passing an MBA exam at Wharton to writing a biblical verse about removing a peanut butter sandwich from a VCR, its rise to prominence does not come without flaws. The tool has flubbed basic arithmetic, and it has been shown to regurgitate racist and sexist content without hesitation. Conservatives also allege the AI chatbot leans liberal.

But its biases can also be used to pinpoint issues of equity in humans too, since the AI’s conversations reflect information originally added to the internet by real people. Koretsky is currently studying how artificial intelligence programs reflect racial biases in grading, for example, examining whether they award higher marks to students who write in a style most familiar to white middle- and upper-class students.

Koretsky said he and his researchers may be able to extrapolate from the results where biases are likely to exist in instructors. The research is one example of the way artificial intelligence can be used to shape educational policy in the future.

“I think you need huge perturbations to the educational system to knock it into a different equilibrium state,” Koretsky said. “Depending on the response of educators and education institutions and larger society, we have an opportunity to land in a better place.”