A group of Tufts graduate students in the School of Arts and Sciences, the School of Engineering and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts has been working toward forming a union for graduate students, following the National Labor Relations Board's (NLRB) ruling last August that graduate students at private universities, as paid teaching and research assistants, have the legal right to unionize.

Last semester, the Graduate Student Council started an ad hoc committee to gather information about unionization. Starting in February, this committee transformed into an organizing committee, ready to take the necessary steps to create a union, according to organizing committee member and English Ph.D. candidate James Rizzi.

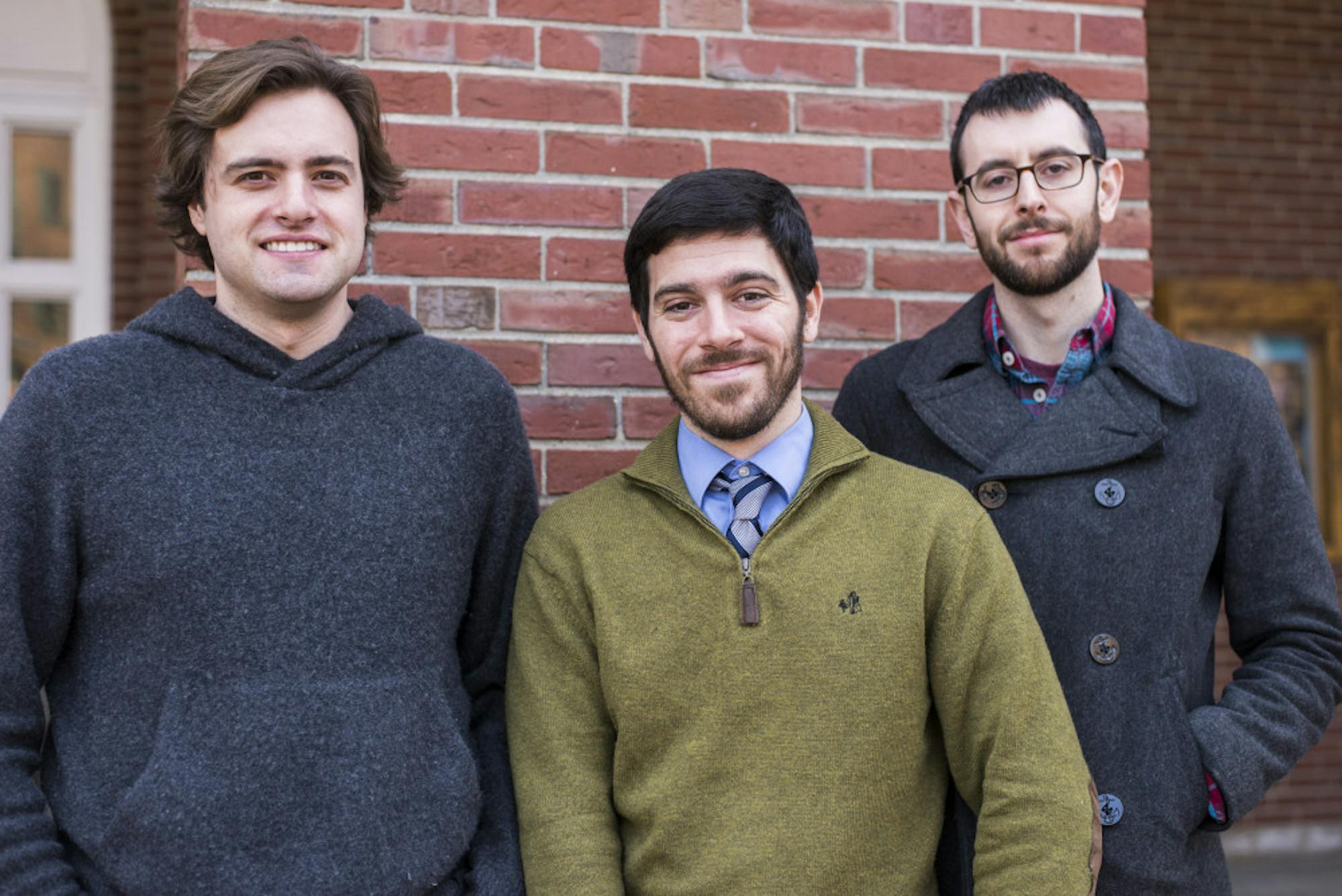

Many on the organizing committee, such as Eric Fields, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Psychology, see the union as a positive step for graduate students, both practically and philosophically.

“Unions give more people power and voice in their workplace. Given how much work structures our life … when people can have more of a voice in a workplace, that leads to a more democratic society,” Fields said.

Yet not all Tufts graduate students share this vision. Some students see a union as unnecessary, with the potential to undermine the benefits graduate student employees already have, according to Piers Echols-Jones, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Mechanical Engineering.

“Most people I speak to are wary [of unionization],” Echols-Jones said.

In contrast, both Rizzi and Fields said most people they spoke with were receptive to unionization.

The differing views of these graduate students reveal the core debate around forming a union at Tufts as well as the uphill battle organizers face as they strive to obtain enough support to hold a union election.

Rizzi said that, fundamentally, the key advantage of a union is its ability to give graduate students both the ability to bargain their own contracts and an opportunity to more clearly define their roles.

“[A contract] would stipulate things that we don’t have now, like grievance procedures or the ability to negotiate for different benefits or better pay,” he said. “We would have a much more defined set of priorities, benefits and salary and responsibility as well.”

In addition, a union could also help ensure graduate students are paid fairly, Rizzi said, especially as the cost of living in the Boston area rises.

Fields noted that a union could help procure summer funding for graduate students, which Fields said is currently not guaranteed for his colleagues in the Department of Psychology.

“You’re expected to do research over the summer. You’re not going to finish your degree in the allotted time if you don’t, but you’re not guaranteed to have funding,” Fields said.

Additionally, Rizzi said that, with Congress likely to repeal the Affordable Care Act, a contract could help ensure graduate students have quality health insurance. Fields noted that, as of now, Ph.D. students who take more than five years to finish their degree are not given health insurance.

“In my department … about half of students [take] more than five years to finish their degrees so that’s pretty normal, but you no longer get health insurance in your sixth year and you have to pay for it yourself which is pretty expensive,” Fields said.

However, Echols-Jones believes that Tufts graduate students are already paid fairly well compared to other students in the area and that a union would be unnecessary.

“For the most part, everyone seems really satisfied,” he said. “We recognize that as grad students we don’t have a lot of spending money. Our stipends aren’t huge, but it’s something we volunteered into.”

Echols-Jones worries that unionization may actually undermine the benefits he said he and other science, technology, engineering and mathematics students already have. He noted that a rise in graduate student pay could take money away from other important areas such as research or hiring quality professors.

“If they’re paying their grad students more, that’s siphoning off money for something else,” he said.

Fields said that, while he understood Echols-Jones' concern, in practice, students would not lose anything, especially when looking at other graduate student unions in the country. Graduate students have long been able to unionize at public universities in certain states, and the August NLRB ruling allowed Columbia University students to form a union.

“If you look at places where grad students got unions, nobody has ever lost anything,” Fields said. “The goal is to bring up people who don’t have it as good and never to bargain away something that someone already has.”

However, Echols-Jones expressed concern that students supported by outside grants could lose their funding if stipends become too large for these organizations to pay.

“Students who are funded by grants rather than departments have a concern because if there’s a stipend increase, that’s a higher cost on everything,” Echols-Jones said. “There’s a concern if that’s affordable with grants or if a grant can meet that requirement.”

Fields noted this as a concern but felt that students who receive grants would not need to worry. According to Fields, research has shown that unionization has not harmed students' ability to do research.

A 2013 study cited in the August NLRB case found that unionized graduate students at public universities reported more faculty support and equal levels of academic freedom compared to their non-unionized counterparts and were found to be paid at higher levels. The study did not specifically discuss the impact of unionization on research grants.

Even if the concerns of students like Echols-Jones are not met out in reality, Echols-Jones said that by forcing workers to opt out rather than opt in, unions can undermine individual freedom.

“[The union] decides everyone is in the bargaining unit and you have to opt out of it rather than opt in … If you vote no [on unionization], you’re forced to be part of a union, [if] it passes," Echols-Jones said. "This is, in my opinion, a really anti-liberal thing to do. It’s not good to force someone to be in an organization they don’t want to be in."

Rizzi said that if individuals opt out, they will be entitled to the benefits of the contract the union organizes, but they will not have a voice at the bargaining table.

“You are still part of the bargaining unit, you don’t negotiate on your behalf, you still get all the advantages of the contract that is ratified and you pay a lesser fee to the union,” Rizzi said.

Those who choose not to be part of the union must pay 1.27 percent of their salary to the union, whereas union members must pay 1.5 percent, Rizzi said. Rizzi noted that these fees are mandated by the federal government, not the union itself.

Currently, graduate students are working with representatives from Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 509, which currently represents the adjunct faculty at Tufts. Meg Tiley, a SEIU organizer working with the graduate students, declined to comment for this article.

Starting last semester and continuing into this semester, union organizers have been collecting union cards, which indicate individual members’ interest in holding a union election, according to Rizzi. Federal laws state that an election can be held once 30 percent of employees sign union cards indicating their support to form a union.Rizzi and Fields said they are not sure if an election will happen this semester, because they first want to ensure unionization has broad support.

“You want mandates. You want overwhelming support for moving forward. You want people to be actively involved. You don’t want one group of 10 people making decisions for thousands of students,” Rizzi said.

Tufts Executive Director of Public Relations Patrick Collins told the Daily in an email, "We are aware of interest among some graduate students in the possibility of unionizing and look forward to working with them on this issue at the appropriate time."

The future is particularly uncertain given the current political climate. President Donald Trump has made anti-union statements, and he has the power to appoint people to the five-member NLRB when its current members' five-year terms end. These appointees could potentially overturn the August decision.

While Rizzi said they are working to adjust to the changing political climate, he is hopeful that progress will continue.

“I think the overall tide in academia is moving towards recognizing graduate students as essential employees to the university,” Rizzi said. “Even if this current effort were not able to make progress towards its goals, we’ve made headway and been able to put in place an organization structure that could be used in the future.”

Graduate students consider unionization following NLRB decision