In a joint effort between Tufts and Medford High School (MHS) on Oct. 16,10 Tufts graduate research students in the Departments of Chemistry, Biology and Biomedical Engineering presented their doctoral research projects to MHS students in the first-ever Reverse Science Fair.

The Tufts graduate students brought in posters and explained their projects to about 180MHS students in the high school's new lecture hall, according to MHS Chemistry Teacher Brian Mernoff (G '14). The same graduate students are scheduled to judge the high school's regular science fair on Feb. 26, he added.

Every class period, two MHS science classes signed up to attend the Reverse Science Fair, according to Mernoff. He said he encouraged his students to look at the projects that most interested them and to discuss them with the presenters. Students spoke with two graduate students for 15 minutes each.

“The idea wasn't so much to get the students to understand everything that the grad students were presenting,” Mernoff said. “The big intention of the fair was to make a connection with a real scientist and see what it's like to do [actual] research.”

The idea for the event was initially pitched by Mernoff and Professor of Chemistry Charlie Sykes, who both sought to increase engagement between Tufts and MHS, according to Mernoff. He said that they discussed the idea this past summer with Medford Public Schools Science Coordinator Rocco Cieri and later brought it to Tufts Chemistry Outreach Assistant Karen O’Hagan, who reached out to graduate students to volunteer to present their projects.

O’Hagan said that outreach programs like this one are important for both the graduate students and high school students because they remind the researchers that others are excited about the work they are doing.

"In all of the outreach programs, we see a renewed energy in the graduate students," she said.

According to Mernoff, although participating in the annual science fair used to be required for just MHS first-year, this year the requirement shifted so students in every grade level participated. He said he hopes that the Reverse Science Fair invigorated interest in the high school students to begin their projects.

Mernoff explained that after leaving the science fair, his class wanted to keep discussing the projects and expressed interest in future opportunities in scientific research, and that he heard similar responses from other classes at MHS. He and O'Hagan said they want to expand this event to occur over a two-day span next year so that more MHS students can benefit from the experience.

“I think it showed them the real connection and application of what we ask them to do,” Mernoff said. “[High school students] see on [graduate students’] posters that they have the exact same steps and organization of their projects. It's the exact same thing but even more drawn out over several years, even. I think they'll really see going into this [next] science fair how closely connected the science fair is to the real world.”

According to Mernoff, the nature of the Reverse Science Fair allowed the graduate students to practice presenting to an audience who did not have expertise in that area.

“It was nice to see them trying to figure out [how much detail to share], and as the day went on, the grad students actually growing in being able to communicate much more clearly to high schoolers what they were doing, using language they would understand,” he said.

Amanda Aldous, doctoral student in the Department of Chemistry, presented her work on inducing constraints on peptide sequences to the MHS students.

“Normally when you're presenting your research, you're getting more blank stares and people are more 'judge-y,'” she said. “You usually have a lot of faculty or higher-up people who are questioning you on very specific details, but the students were just really interested. We had their full attention.”

Aldous said that when she began listing her failures in response to a question over the challenges she has faced in her research, one student seemed surprised that she had run into so many obstacles.

“It was kind of an interesting interaction because you could tell that they didn't realize that what you end up presenting on is a very small fraction of what you actually did,” she said. “I’d like to think that as they are doing their science fair projects, it's not all gonna work the first time around, and they're gonna have to try something different were they to notice that their hypothesis was wrong, and kind of understanding that that's OK."

Aldous said she is hopeful about the impacts of the event and is looking forward to seeing results when she returns to MHS to judge the science fair in February.

Mernoff added that he was delighted with the outcome of the first Reverse Science Fair.

"It was beneficial for both the high schoolers and the grad students," he said. "Both of them learned something. The high schoolers learned what it's like to be a scientist, and the scientists learned how to present to a general audience."

Tufts and Medford High School hold first-ever Reverse Science Fair

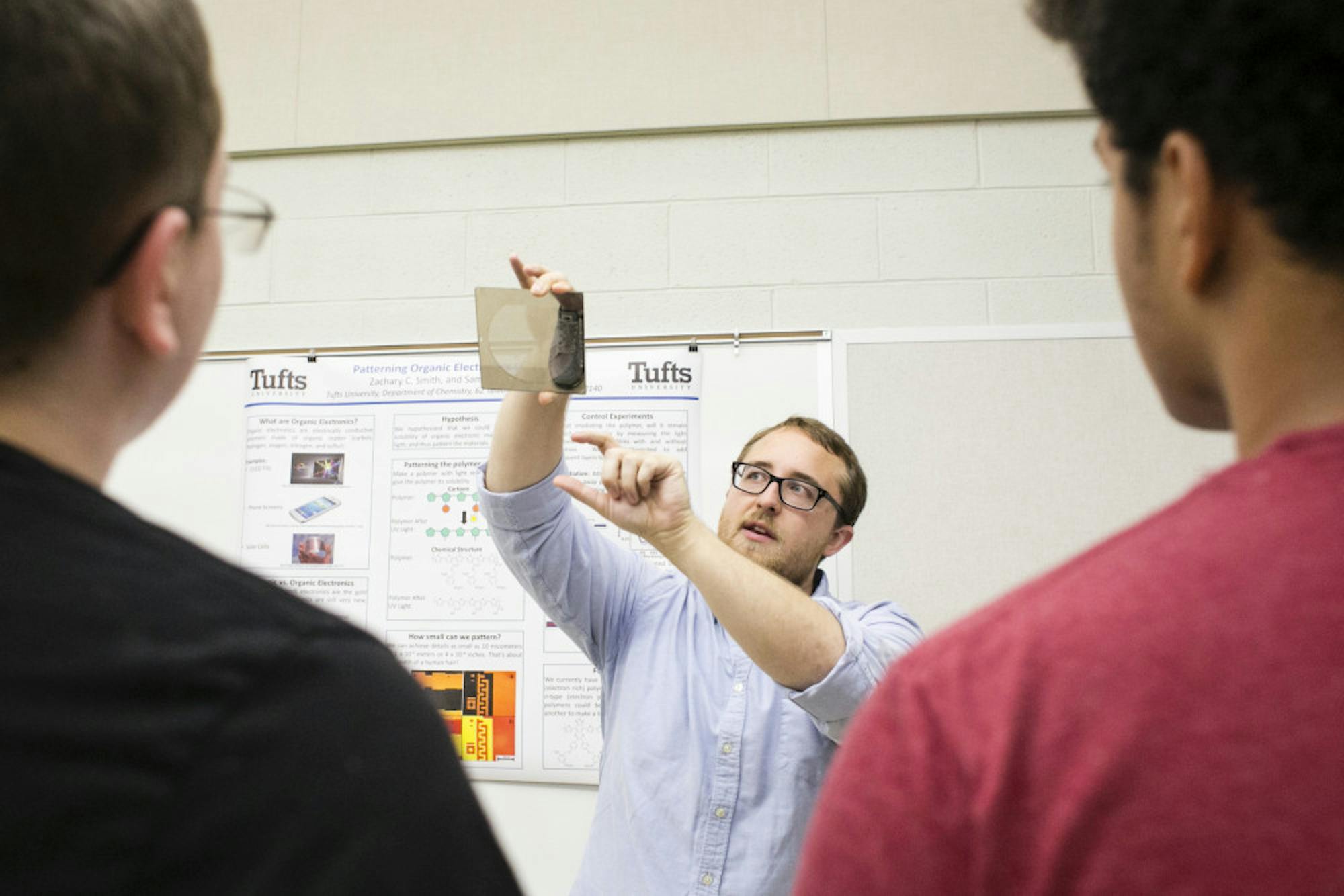

Zachary Smith, a doctoral student in chemistry, gives a presentation to Medford High School students during the Reverse Science Fair on Oct. 16.