The Special Collection at Tisch Library boasts an impressive array of rare books from ancient to modern, including medieval transcripts and the personal library of Tufts’ founding president, Hosea Ballou II. The collection of old books and manuscripts cover a wide variety of subjects, from cuneiform tablets to choral books used by medieval monks. While not widely known, the collection offers much insight into how books, as a medium of knowledge, have evolved throughout centuries.

The origin of the collection can be traced back to Walter F. Welch Jr.’s (A‘28) donation of a collection of rare books including ten transcripts from the medieval and renaissance periods, as well as dozens of early printed books. By donating the books in the 1950s, Welch intended to provide students with sources about how the practices of bookbinding have changed over time and pass down his literary enthusiasm for future generations of students.

While Welch’s donations were safely stored in Tufts’ libraries for decades, the collection did not have a dedicated rare book librarian. Instead, the collection was under the management of the university archive. As most of the books were not cataloged, the majority of the collection remained inaccessible. The situation only began to change when the current Curator of Rare Books, Christopher Barbour, was hired in 1997 as the first rare book librarian at Tufts.

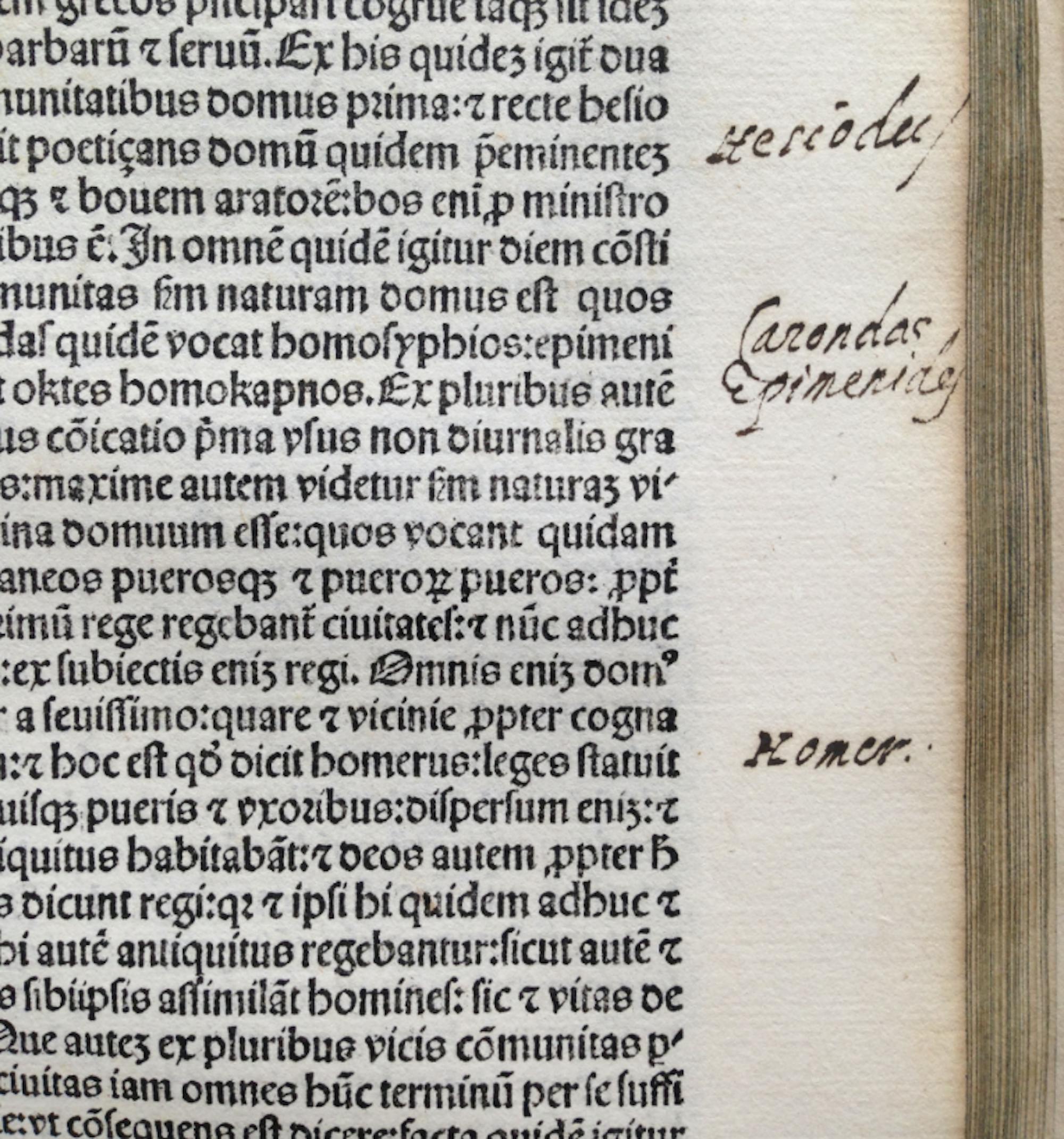

“From 1965 to [the] early 1990s, that collection, with its two reading rooms, was on level three. It was never staffed by a rare book librarian [and] didn’t have much staff at all,” Barbour said. “So the book collection was rather neglected for want of staff. It was challenging. The Latin material, particularly the manuscripts, were never cataloged, so they weren't known,” Barbour said.

When Barbour first took charge, the collection was not well organized. But over the years, much work has been done to uncover those hidden treasures in an interdepartmental effort. According to Barbour, when several fragmented medieval manuscripts were uncovered in 2008, they were only understood with the help from professors Karen Overbey and Cristelle Baskins, both of whom are now associate professors emerita in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture. Another figure who was instrumental in helping to understand the collection and who gave it international exposure was Anne-Marie Eze, an associate librarian at the Houghton Library at Harvard University.

“Ultimately, Anne-Marie would not only help us understand the quality of our collection, particularly Welch’s donations, but bring exposure to our collection through a major exhibition of pre-modern manuscripts,” Barbour said. “In 2016 in Boston, at the McMullen Museum, at the Gardner Museum and at the Houghton Library at Harvard, there were over 250 manuscripts [displayed], including three from Tufts collections.”

History professor Alisha Rankin, who specializes in early modern European history and medieval history, was one of the first faculty members to use the collection for her classes.

“I’ve [used the collection] in classes at all levels from introductory undergraduate classes, so my survey on Renaissance and Reformation in Europe … all the way up to a graduate level seminar on medieval religious manuscripts,” Rankin said.

Rankin has even used rare artifacts, such as a small collection of cuneiform tablets and Roman papyri for a course on the history of books.

In September 2022, a new space at Tisch — room 103 on the ground floor — was dedicated to the exhibition and display of collection materials. It currently features an exhibition about the life of Frederick Douglass in honor of Black History Month. In addition to making the collection more visible to students who pass by daily, this change also made access easier for classes.

“The other space they were in before was up off of the Digital Design Studio. There is this giant room that they would put the exhibitions in. … I would teach classes there, and I'd always have to explain to students how to get there, and this new space is much more easy to find,” Rankin said.

Though relatively few in number, the handwritten manuscripts in the collections have been particularly valuable due to their historical and aesthetic values. The subject matter of collected materials varies based on specific time periods.

“There are often manuscripts that have been written by members of religious organizations, most of them by male religious [authors], but [for] most of them, we don’t know who actually wrote them,” Rankin said. “It’s a nice mix of things, there [are] some early music [books], there [are] a lot of prayer books, there are some books of hours, which are meant for lay people to use for prayers.”

For the average peruser, the collection may be difficult to fully interpret.

“If you don’t know Latin, they are hard to read. They look nice, but it’s hard to figure out,” Rankin said. “But there [are] a couple of them that have really nice illustrations.”

The costliness of the parchment on which those manuscripts were produced, in addition to the difficulty of preservation in latter days, has made those manuscripts a rare resource. To better preserve the collections, all the books are stored in a separate heating, ventilation and air conditioning system from the rest of the library, where the humidity and temperature are controlled to ideal conditions.

One of the most notable manuscripts from the collection is the Paris Biblefrom the 13th century. It was created in a type of workshop called a scriptorium, which could be found in medieval monasteries where manuscripts were written and illuminated by hand. According to Rankin, manuscript pages were made out of animal skin, yet were still very thin and contained highly intricate writings and illustrations.

A highlight of the Paris Bible is the carefully illuminated initials that can be found throughout its pages. Each book of the Bible within the manuscript begins with an initial that is decorated with an image, often miniature illustrations of biblical concepts. Apparently, the handwritten transcription would require strenuous teamwork far greater than how books are printed today. Barbour described the process of creating a work such as the Paris Bible at the time.

“I like to call it a portable gallery of medieval art,” Barbour said. “[The Paris Bible] was constructed by a team of scribes who could produce this uniform script that’s very difficult to tell where one scribe leaves off and the other begins. There would have been another person or persons who just specialized in doing those minor pen work initials, and perhaps, also these headings. … And then the illuminator, or illuminators, would be a team working with a universal style. So, all these people were involved. And then, there is the bookbinder, [and also] the person who rebound this book at some point, possibly in the 17th, maybe 18th century.”

The high level of detail that is seen in the 13th-century Paris Bible could only be possible due to the production of vellum, a high quality form of parchment. The texture of the Paris Bible stands in sharp contrast with another notable piece from the collection, which is a 14th-century antiphonary, a piece of work intended to be sung by a church choir. The antiphonary was written on a parchment that was much coarser, with features of animal skin still visually perceptible.

“[If you tried to write] all the books of the Bible in the size of this parchment, you wouldn’t be able to shut the book,” Elettra Conoly, special collections assistant at Tisch Library, said. “It was really a technological innovation to be able to create parchment that thin that you could put the entire Bible into one volume.”

In addition to the medieval collection, the Tisch Special Collections include several important pieces of early modern political thought literature. Professor Ioannis Evrigenis of the political science department has utilized those resources for a project he is leading called Bodin@Tufts, which aims at a new translation of Jean Bodin’s “Six Books on the Commonwealth.” For various classes he teaches, Evrigenis has taken students to the collection to visit the first editions of work by political thinkers like Hobbes and Rousseau.

As these ancient books have become not only a wealth of knowledge but also cultural artifacts from the past, studying them can often raise important questions regarding epistemology and politics.

“These books and manuscripts are an unusual sight nowadays, but they give you a sense of perspective into how we got to where we are, and they get you thinking about … how knowledge gets disseminated and how one makes a decision,” Evrigenis said. “It raises all sorts of important political questions.”

For Rankin, the collection has provided other insights.

“The medieval religious manuscripts in general gave me a really new appreciation for the process of religious prayer,” Rankin said. “It does make a difference having the materials in front of you. … You can get a sense of how these were living objects that were used, and I think that’s unique.”