The founding of Tufts has been a tale told far and wide. When a friend of Charles Tufts, one of the founders of Tufts, asked him what he intended to do with land including Walnut Hill, the iconic centerpiece of campus, Charles proclaimed that “I will put a light on it.”

This statement has been interpreted by many as a testament to the university’s commitment to excellence and diversity. However, it shines a light on the institution’s uncomfortable relationship with the generational trauma of slavery.

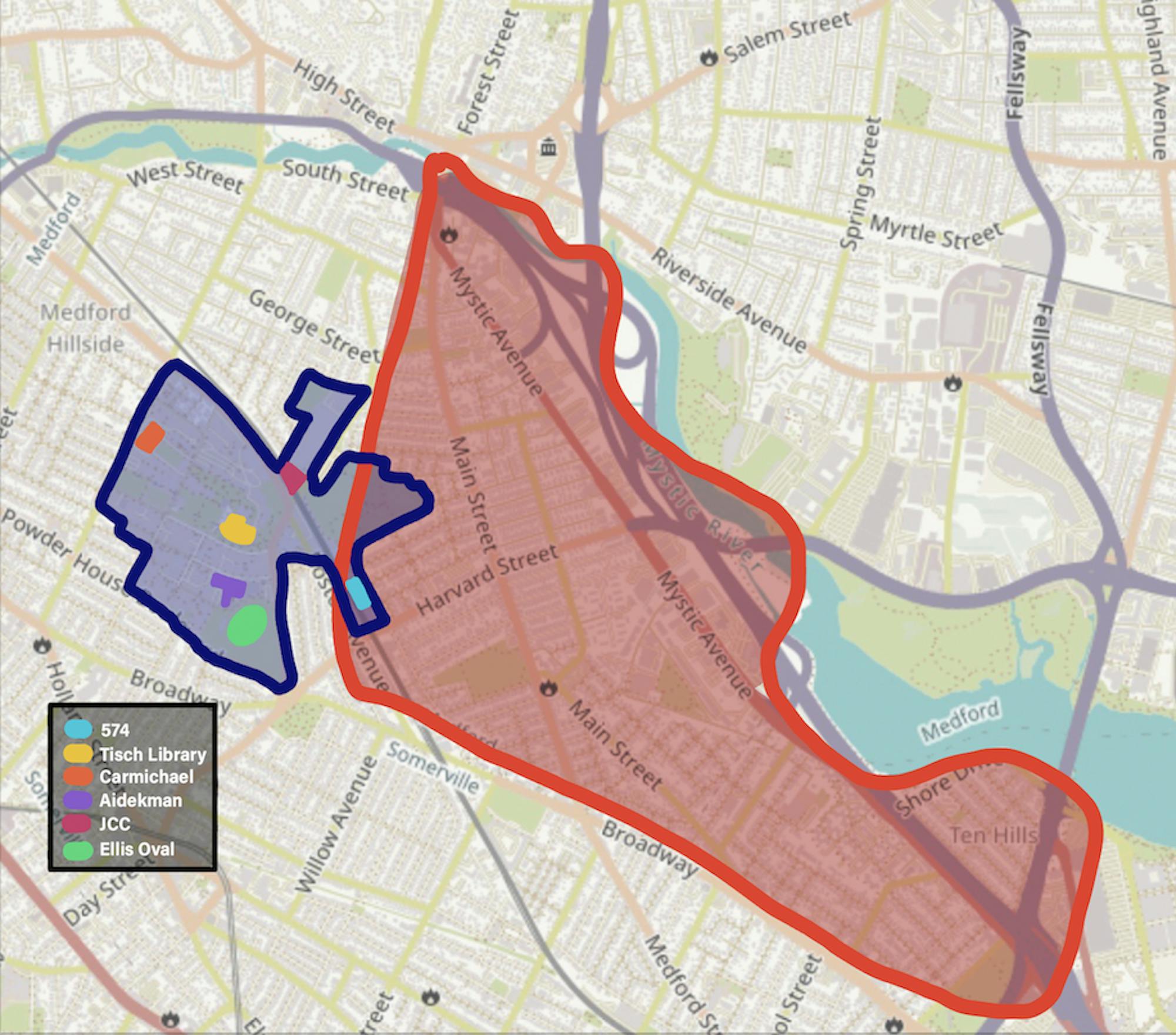

Walnut Hill was integral to Tufts’ founding in 1852, but it was also critical to the establishment of the Ten Hills Farm. Granted in 1631 to Massachusetts Bay Colony Governor John Winthrop by the General Court, the farm comprised of 600 acres of land that were utilized as a slave plantation. Such acreage encompassed swaths of the western side of the Mystic River, which included land on its northwestern end that is now incorporated into Tufts. The farm’s name came from the fact that 10 hills influenced the topography of the plantation, including Walnut Hill.

This history has been evaluated by historians in marginalized communities for generations, and Kerri Greenidge, assistant professor of studies in race, colonialism and diaspora, knows this well. She is also the co-director of the Tufts African American Trail Project at the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy, which is an initiative that “aims to develop African American historical memory and intergenerational community,” according to its website.

Greenidge attested to the impact of this scholarship.

“African and Afro-Native communities in New England have been covering this history for a long time,” Greenidge said. “[The Center for the Study of Race and Democracy is] becoming a place … that people can have a paper map … that shows the extents of Afro and Afro-Native communities across Massachusetts and from the 1600s all the way up to the present … [along with] honoring the work that local public history sites have done.”

Associate Professor of History and Studies in Race, Colonialism, and Diaspora Kendra Field, who is also the director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy, further discussed the scholarship being conducted by those at Tufts on this history.

“There’ve been a few … oral history projects related to these neighboring communities, particularly the West Medford community [that] sent a number of Black students to Tufts,” Field said. “It’s not just [a situation where] it is beyond the walls of Tufts. There were actually active, dynamic relationships between that community and students and faculty here.”

The presence of the local slave market was palpable. A French visitor, whose observations are preserved by the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Mass., stated that “you may … own Negroes and Negresses. … There is not a house in Boston, however small may be its means, that has not one or two. There are those that have five or six.”

Nowhere was the power of local slavery more evident than in the Royall House and Slave Quarters, a part of the Ten Hills Farm that is just short of a half-mile walk from the Joyce Cummings Center. Greenidge detailed the origins of the House’s founder, Isaac Royall Sr., who bought the house in 1732.

“We know that the Royall family … was part of this Atlantic world [of slavery],” Greenidge said. “[Isaac Royall Sr.] migrated from Antigua, where he was a slave holder, and he moved to the area of what is now the Royall House and Slave Quarters. … The building that [currently exists] is probably … one-eight of the actual size of the Royall plantation.”

Greenidge further discussed the Royall family and the questions that are remaining regarding the slaves that resided at the Royall House.

“The Royalls were loyalists, so they actually ended up fleeing at the end of the Revolutionary War,” Greenidge said. “We know that formerly enslaved … African American people lived in the area that we now think of as West Medford and Tufts after slavery formally ended. One potential … project on the relationship between Tufts and slavery … would [focus on] what happened to those people. Did they own land? Where did they live? And how does that relate to … Tufts’ commitment to, or not, to educating that very vibrant community of color that lived in the area?”

The Ten Hills Farm was influential in the founding of Tufts. As the farm was still operating, a man named Peter Tufts, who immigrated to the United States from Malden, England in 1638, purchased 3.5 acres from another man named John Cary in 1696. These acres constituted Walnut Hill, which surrounded the farm due to a 1685 deal that established land boundaries for individual proprietors.

Charles Tufts, a descendant of Peter who was a farmer and brickmaker, owned 20 acres of farmland that included the Somerville side of Walnut Hill. These acres would ultimately be the basis of College Hill, which is now the location of Ballou Hall. Although the farm ceased activities after Massachusetts abolished slavery in 1783, the land boundaries it formed allowed for large land parcels to become available, which enabled Charles Tufts to dedicate his acreage to the university.

This history of Tufts’ connections to slavery is convoluted, and there are clear historical gaps that need to be filled. However, that does not mean that this history has not impacted Tufts students.

Zoe Schoen (LA’19), a project administrator for the African American Trail Project, attested to how important this history is to her as a member of the Tufts community and resident of the area.

“I feel like, as a former student who now has been involved with the [Center for the Study of Race and Democracy] as an alum, … I wish that I had been more plugged into the work as a student,” Schoen said. “It has really oriented me towards living here and feeling more of a sense of where I am and what this institution is.”

Schoen also detailed how other universities are handling their connections to slavery. Harvard University, for instance, released its “Report of the Committee on Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery” in April 2022.

“I think it’s interesting that we are in a moment where these kinds of official reports from universities have become more popular in recent years,” Schoen said. “I think we are thinking about how … important it is that a more formal project would need to recognize the work that has always been going on.”

As the long tradition of scholarship on this connection between Tufts and slavery continues, the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy is reflecting on the work that has already been done and looking toward future opportunities to further examine this history.

Schoen reflected on the importance of the Center’s work on making students feel grounded.

“I think that ideally, every student who comes [to the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy] … feels a grounding in the place that they are in, regardless of whether you study history or engineering,” Schoen. “[Ideally] it would enhance [one’s] experience here and enhance [one’s] sense of purpose … at Tufts.”

Field discussed initiatives the center operates, which include a first-year orientation program that allows Tufts students to take a bus tour featuring African American Trail Project sites such as the Royall House and Slave Quarters.

“During first-year orientation, there [was] an optional part of the orientation in which Dr. Greenidge and I would take students to the Royall House and immerse them in that, and orientation is a perfect time to do that,” Field said. “It is really powerful, and we have had such amazing students … who were protesting, for instance in 2015 and 2016, police violence following the murder of Michael Brown. … [Orientation] shaped how they engaged with our current historical moment.”

Field also talked about what the future holds for the Center in examining this integral part of Tufts’ history.

“We are part of a larger group of faculty and others across campus who are working with the University to drill down … on the historical chronology and details related to the history of slavery and colonialism … in this place, prior to and including the establishment of Tufts,” Field said. “That project has been ongoing, but it is gaining a larger audience.”

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article listed Zoe Schoen as a staff member of Tufts’ Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. Schoen is a project administrator for the African American Trail Project, which is housed under the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. The previous version also incorrectly quoted Kendra Field as saying “Westminster” when Field in fact said “West Medford.” The Daily regrets these errors.