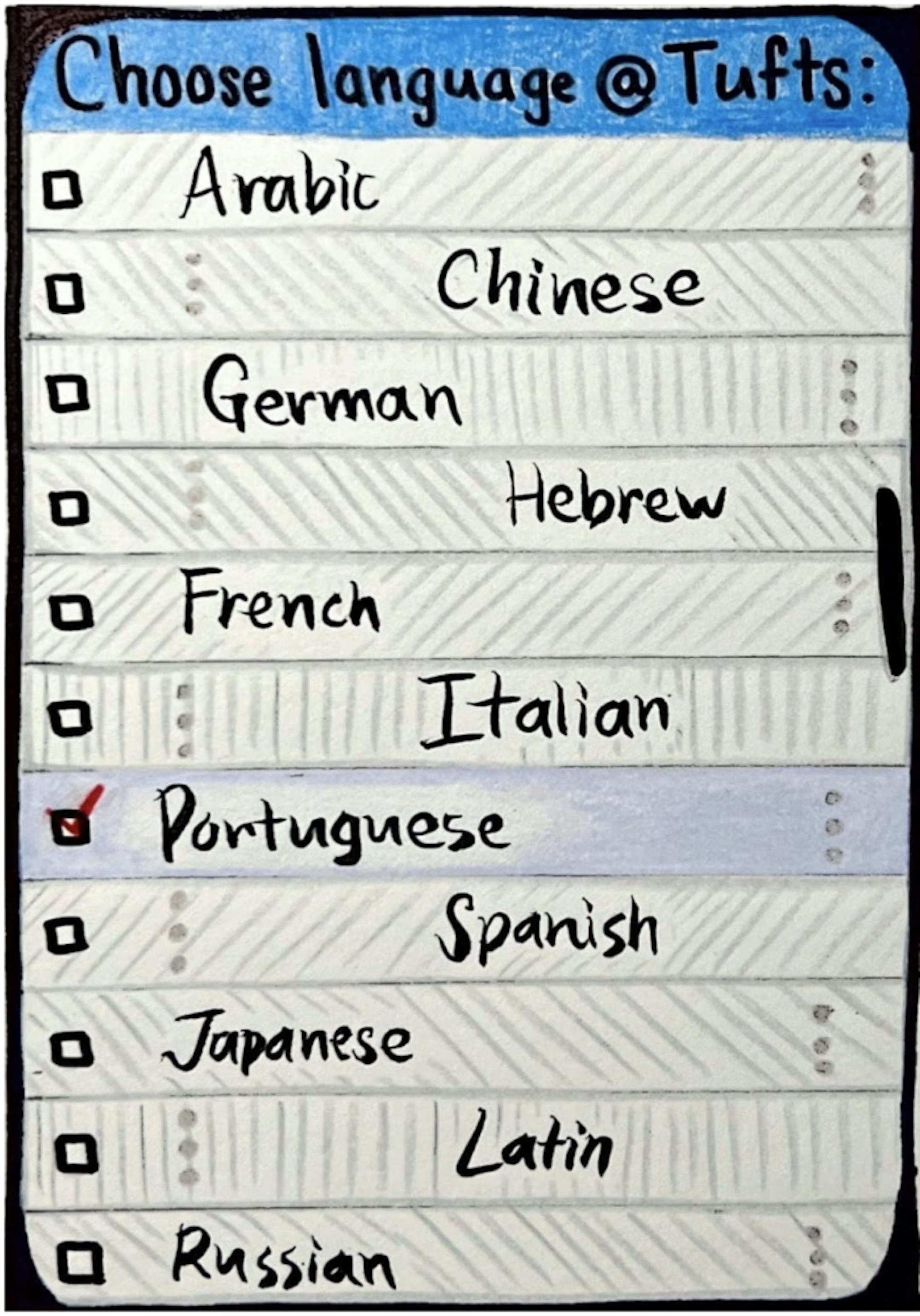

Language programs have always played a curious and multifaceted role in academics at Tufts University. As a foundational requirement for School of Arts and Sciences students who don’t test out through a language proficiency evaluation, they could be considered the closest thing to a universal experience at a school with more than 70 undergraduate majors. Also noteworthy is the extent of the language requirement: The six semesters Tufts students must spend studying another language and/or culture is unusually rigorous for universities of its kind. Language education is also a key part of the international relations major and international literary and visual studies major, both of which require eight semesters of commitment to studying a single language. In this sense, learning a foreign language is quintessential to a Tufts education.

On the other hand, majors that focus particularly on language and cultural studies are more of an academic niche, with the total number of bachelor’s degree candidates hovering around 70–80 per year.

Additionally, while several languages have recently opened new tracks of study, other programs have been at risk of elimination. In light of this, it seems clear that languages’ status as a requirement for graduation and their incorporation into select degree programs are in part responsible for their perseverance.

The status of language education at Tufts is thus complicated and certainly gives rise to some questions. First and foremost, what is the purpose of such extensive language education at the collegiate level? Furthermore, how do Tufts students see foreign language education fitting into their academic career at large? Finally, how are language programs adapting to the interests of their students?

“Tufts has a pretty demanding language requirement … and I think that’s really extraordinary and great, even though I know students resent it at times,” Professor Nina Gerassi-Navarro, the chair of the Romance studies department, said.

She sees the value of language education in its ability to expand one’s perspective.

“Forcing students to really learn a language is much more than just the language,” she said. “It’s the culture; it’s learning to understand a different worldview and to [understand] your own worldview.”

One common reaction to this idea is that such personal transformations can’t be documented on a resume or applied directly to a job. In other words, while undoubtedly meaningful, language education doesn’t serve students in a practical manner.

Professor Charles Inouye, the chair of the international literary and cultural studies program, strongly disagrees with this mentality. In defense of language education, he pointed to a number of skills developed during the study of foreign languages including problem solving, creativity, planning and facilitation of cooperation.

“Those skills are very highly prized, but it takes a while for … them to develop, and … for people to realize their value,” he said.

Above all, Inouye argued that concerns about the practicality of language education are short-sighted.

“I’m very much in favor of having people … prepare for life rather than to prepare for a career,” he said.

Regardless of the intentions behind why students pursue these courses, Tufts’ student body does seem to have a clear vision of how language and cultural studies fit within their academic careers.

“I think more and more, students are interested in … interdisciplinarity,” Professor Samuel Thomas, dean of academic affairs at Tufts, said.

Tufts has attempted to meet this interest in a few overarching ways. The most obvious example of the interdisciplinary study of language and culture is the international relations major, but such courses of study also find a home within the International Visual and Literary Studies Program.

Gerassi-Navarro spoke very highly of the interdisciplinary work being spearheaded by the ILVS program, which currently operates as a collaboration between departments such as international literary and cultural studies, Romance studies and other related fields.

“It doesn’t just do the talk of interdisciplinarity, it … allows you to move forward with that,” she said.

Interdisciplinarity is just one way in which language education is being modernized. Spurred by student feedback, the Romance studies department is attempting to provide greater diversity of course materials besides literature in language classes. According to Gerassi-Navarro, the department recently voted to open a new French track with courses that expand into other forms of cultural media — news which will be announced in classes during the spring 2023 semester.

Gerassi-Navarro reflected on the contents of these new courses.

“It’s less of a traditional way of approaching literature. … It’s also film; it’s also texts that reflect on cultural issues that are not just necessarily novels or essays or poems, and I think that students will like that,” she said.

In many ways, these new and emerging parts of language and cultural programs are encouraging. Students are clearly interested in such programs, and their desire for more modernized forms of teaching demonstrates that language education has a future at Tufts.

Nevertheless, departments still encounter occasional challenges in terms of their ever-shifting enrollment numbers. One example of this is the Portuguese program, which was recently forced to compress Portuguese 1 and 2 into one course called Portuguese for Romance Speakers.

Expounding on the Romance studies department’s efforts to continue offering Portuguese, Gerassi-Navarro expressed that constant curricular adjustments can be challenging.

“It’s just a lot of repackaging that you have to do,” she said.

No matter how language education fares year by year at the university, it seems clear that many members of the Tufts community remain passionate about its inclusion.

“I am really proud to be associated with the language teaching programs … [and with] those programs’ commitment to students, to cutting-edge pedagogy, to not only the teaching of students but the care for students,” Thomas said.

The continued presence of language programs at Tufts has certainly been ensured by their flexibility and willingness to apply students’ interests to their course designs.

What’s more, the rigor of the language requirement has become an established part of Tufts’ academic identity, one that would be strange to renounce.

“It’s really a distinctive aspect of Tufts, and it represents a deep commitment to … the ability to understand other cultures, other people [along with] the ability to entertain values that are not your own,” Inouye said.