American politics have become vividly polarized in recent years, as “the correlation between party and ideology has really tightened,” according to Tufts’ Professor of Political Science Deborah Schildkraut.

Open-minded dialogues between people of differing ideological stances are lacking, both at Tufts and across the nation. Indeed, ‘conservatism’ has taken on strong connotations in many people’s minds, across the current divisive political spectrum, especially on a campus where a majority of the student body is liberal.

Many political conversations at Tufts are not wholly representative of views across the political spectrum. The openness of conversations and perceptions of those with different political ideologies holds great power over how students build their worldviews while at Tufts.

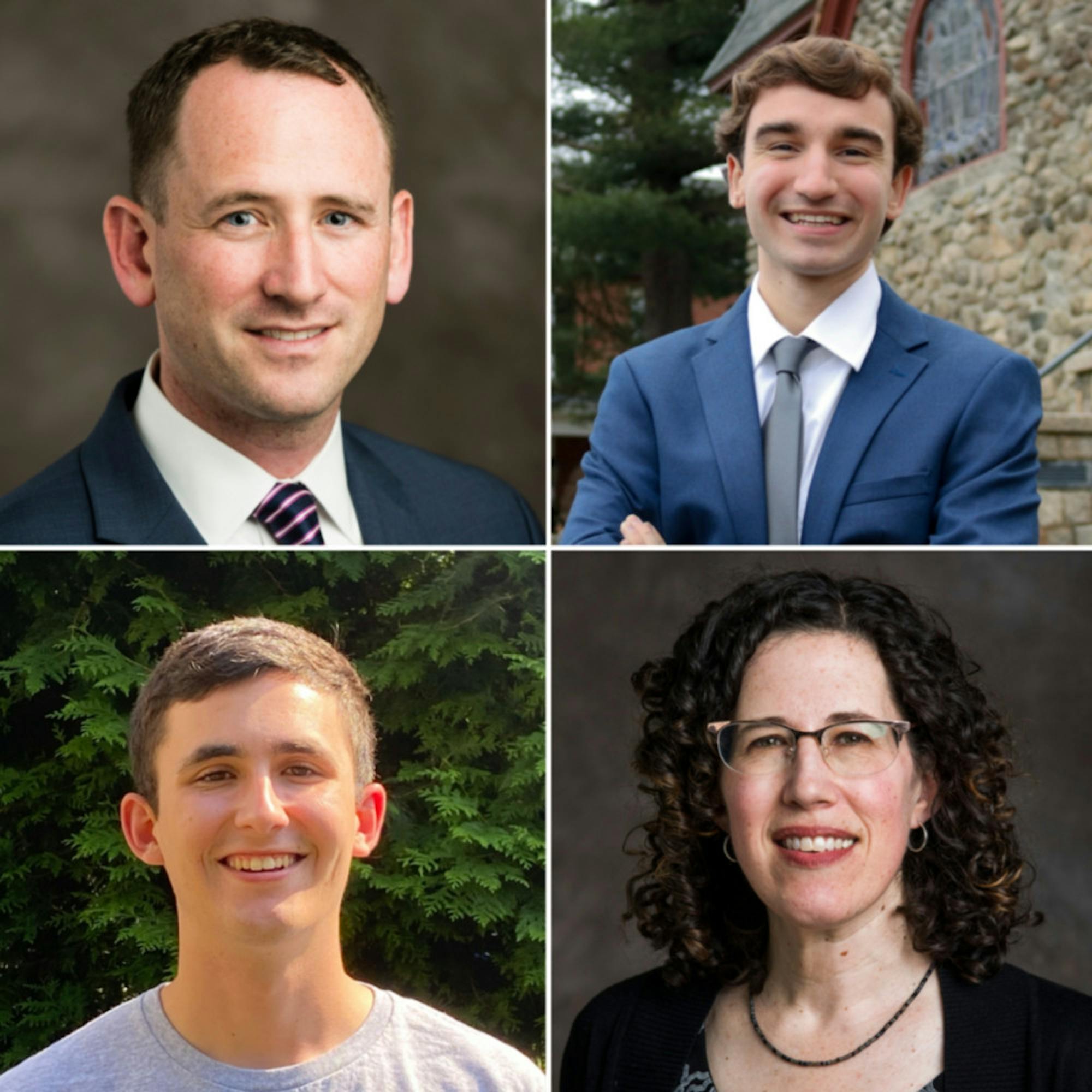

With this context in mind, Eitan Hersh, associate professor of political science, explained his view of Tufts’ political climate.

“I think that Tufts is an unusual environment where the student population is overwhelmingly liberal. It’s even overwhelmingly liberal, it seems, relative to the general population of young adults [and] to the general population of people in Massachusetts,” Hersh said. “I think students find themselves in some kind of a bubble.”

Hersh elaborated on the importance of political diversity at Tufts. He hopes that, through the course, students who identify as conservative will gain a stronger sense of their political ideology and students who identify as liberal will be exposed to perspectives contrary to their own.

“Part of one’s education, particularly in politics, I think should be making sure one understands different perspectives,” Hersh said. “Half of the country finds a lot of value in both that identity of being conservative and in conservative perspectives on major policy issues.”

As Hersh pointed out, the uneven distribution of political views on Tufts’ campus creates a particular dynamic between students. Andrew Butcher, president of Tufts Republicans, said he has observed a social stigma around conservative voices and perspectives at Tufts.

“There’s always that fear of the human tendency towards tribalism, and there’s a very significant, and I personally would claim not unfounded, fear that if people were to realize that their classmates or their students were conservative, that would negatively affect that student,” Butcher said.

In this context, Tufts Republicans aims to provide a space for open-minded dialogues on conservative ideologies, according to Butcher. He further articulated that the club’s twofold purpose is to “advocate for and forward conservative values and policies on campus,” and to provide a space for those with conservative ideologies to discuss their viewpoints without fear of judgment by their peers.

This sense of community and commitment to conversation, Butcher emphasized, is the most vital function of the Tufts Republicans on a predominantlyliberal campus.

Still, questions remain. Are students open to discussing ideologies across the political spectrum? Are students challenged to think beyond their own opinions? What do students gain from a politically diversified education, inside and outside the classroom?

In thinking about these questions, the Presidents of Tufts Democrats and Tufts Republicans as well as with Political Science Faculty Hersh and Schildkraut offered a wide range of perspectives to consider.

Beyond scheduled interclub debates between the Tufts Republicans and Tufts Democrats, such as theCIVIC debate, there is a lack of cross-party dialogue on campus, according to Butcher.

Butcher explained a potential reason behind the lack of interaction across political differences.

“As with any ideology, or any perspective, there can be a little bit of circling the wagons. There can be a little bit of a tendency to just go, ‘We think this, we’re right … the other people are wrong, and we don't necessarily need to go out and start those conversations,’” Butcher said.

To counter this trend, Butcher underscored the importance of open dialogues, which can help shape students’ political views and understandings.

“I would love to have more conversations with people who disagree with me on things. I think those conversations are really interesting. I think that if people approach it well, you can change minds,” Butcher said. “I look at myself as a testament to that. I did not used to think the way that I do. … I think we rob ourselves of some really great experiences of discussion when we aren’t willing to open our minds to change.”

On a mostly liberal campus like Tufts, political dialogues look different for students of differing ideologies. Butcher explained that being in the minority, as a right-leaning student, can stimulate personal and intellectual growth.

“Conservative students who go into more liberal institutions wind up a bit more politically informed and get more out of the experience than a liberal student who goes into a liberal institution. And I think that if academia ran more conservative, the converse would be true,” Butcher said. “Walking into an environment where you are challenged on your viewpoint, almost every day, will lead to you sharpening that viewpoint or changing it.”

Mark Lannigan, president of Tufts Democrats, shared Butcher’s concern that Tufts students do not have enough cross-party dialogues on campus.

“I do think we should have more open dialogue, and I do think we should have more back and forth,” Lannigan said. “I think it’s just difficult right now, with misinformation that’s out and this kind of truth denial philosophy that’s going on on the right, to have those dialogues in a very meaningful manner.”

Lannigan further elaborated that “politics has become very personal for people,” making it difficult to have open dialogues from differing ideological standpoints.

Lannigan also spoke of the distinct perspectives within the Tufts Democrats club.

“I’ve certainly challenged my own beliefs with people who are in the club and are like-minded and are Democrats themselves,” Lannigan said. “We go back and forth about differences in ideas and strategy and all that, and I think that’s productive.”

In terms of being challenged through broader open dialogues, Lannigan shared that he has had professors with a diversity of opinions and conversations with peers that hold “competing ideas of what the Democratic Party should be.”

“I feel like my views have been challenged by people within the party, which maybe doesn’t challenge them incredibly far,” Lannigan said.

The topic of open dialogue is particularly important in the classroom context as well. Hersh is teaching a new course in the spring, titled American Conservatism, which aims to expose Tufts students to conservative ideologies and policy positions with the goal of broadening their perspectives and creating diverse, across-the-aisle conversations.

“In order to really engage in a healthy dialogue, students need to really cultivate a sense of who they are and what they care about and what their values are,” Hersh said. “And I think, unless you’re actively cultivating a sense of political identity and grappling with policy issues in a classroom setting, it’s harder to go into a dialogue.”

In a politically charged moment, open-minded dialogues are more vital to the health of democracy than ever. The way in which students view ideologically different parties, as well as their experiences of cross-party dialogues, can influence how they vote. Lannigan expressed his views on the likelihood of students voting along party lines in the midterms.

“I do think there’s definitely more emphasis on voting pure party, not just from people’s own … partisan conception, but also parties are encouraging people to vote down the party line,” Lannigan said.

As students navigate different political ideologies, identities and party affiliations, open dialogues are critical to understanding the difference between ideology and political party and how that can play into voting.

To this end, Hersh hopes to contribute to the dialogues through his course on American conservatism next spring. The difference between these two markers can be better understood in an academic environment, according to Hersh.

“I want to, in teaching a class on conservatism, separate Republican identity from conservative identity,” Hersh said. “I think they’re two different things. And I think you can make a strong case that a lot of the contemporary Republican policies are actually inconsistent with conservative values.”

Echoing Hersh’s sentiment, Schildkraut explained the importance of parsing out the difference between the Republican party and conservatism as a political ideology.

“If one of the big pillars of conservatism in the United States was a notion of minimal government, kind of a libertarian strain. I do think that it does seem to be in flux when you see conservatives in state governments proposing [and] dictating what can be taught in schools or who people can marry,” Schildkraut said. “That seems to contradict the notion of having minimal government.””

At the end of the day, the ways students engage in political dialogue, including the breadth of opinions they are exposed to, is greatly important to developing a sense of political identity.

Along these lines, Hersh urged Tufts students to engage and grapple with perspectives that might be contrary to their own.

“I would say that students should just really read widely and make sure that they are learning from a diverse set of voices,” Hersh said. “If there’s an issue that is divisive in the country, … and if students haven’t really grappled with, ‘Why do people disagree with them? What’s going on the other side of the issue? Who would I talk to to learn about that in a serious way?’ then they’re just sort of in [an] echo chamber.”