Being uncomfortable is never easy. It requires us to propel ourselves outside our personal boundaries, the echo chambers we constructed from the moment we felt empowered to be on one side of the political aisle. Unfortunately, we often fail to branch out and rely instead on our emotional investment in political issues without fundamentally making an actionable plan for political change. Such a practice is called political hobbyism, and Associate Professor of Political Science Eitan Hersh is all too familiar with it.

“[Political hobbyism] is doing politics … without any goal-orientation or strategy. It’s doing politics for fun or for some emotional connection … but you are not actually seeking any particular goals,” Hersh said. “So you do politics for your own gratification. Maybe you learn a lot of facts, you learn about polls or you get emotionally ramped up by watching outrageous videos, and that gives you this feeling of emotional connection without doing anything.”

In his book, “Politics is for Power” (2020), Hersh outlines the consequences of political hobbyism for the American political system. In a significantly inflamed political environment, it has become more challenging for politicians and people to seek compromise on salient issues, and political hobbyism is a practice that adds to such difficulty.

In this context, Hersh explained that political hobbyism can frustrate bipartisan policy efforts, as it can distort people’s perception of how politics really works on the ground.

“The consequences mainly for people are like, they are not going to get what they want out of the government and they’re not know how [the] government works,” Hersh said. “If you look at how policies are actually passed … it requires majority votes or sometimes a more like a consensus model. … In Massachusetts, [for example,] our state operates in a sort of a consensus model, which is that the political leadership doesn’t like moving forward on state policies, unless business and labor and … everyone is on board. That model is totally different from … political hobbyism where they want things to be moving quickly and they make enemies.”

In the American political lexicon, bipartisanship is increasingly perceived as an unfavorable word. As a study conducted by Alan Abramowitz and Steven Webster demonstrates, negative partisanship has continued to grow, resulting in trends such as a decrease in the amount of voters who split tickets during an election.

An overriding factor contributing to such political animosity is the nationalization of politics, Hersh added, which has led to both Democratic and Republican party leaders prioritizing and fighting over nationwide issues rather than local and statewide issues.

Hersh sees this trend and is worried about its implications on the American political system.

“I think you can have better arguments and better discussions, and a better chance at bipartisanship at the state level than at the national level,” Hersh said. “We don’t need to be fighting over everything at the national level. We don’t need to be passing trillion-dollar bills that try to do everything in one fell swoop. I think that the move to nationalize every conversation is really bad for polarization.”

In this context, Magali Ortiz, co-president of CIVIC, added that Tufts’ political environment has created a sort of echo chamber, which can limit students’ political imaginations, in her view.

“Going out into Somerville and Medford proves to you that … [our] campus is a chamber that is self-sustaining, and sort of isolated in a way,” Ortiz said. “It’s interesting to see [that] even though Tufts … pays lip service to this idea that they are engaged in the community, what does it mean to actually do that and bring in those [different] perspectives?”

Breaking out of this echo chamber would require a certain approach to political conversations. Ortiz distinguishes between different forms of civility she learned from attending a conference in the spring of 2022 that focused on civil discourse on college campuses.

“A big distinction that one of the [speakers] made was [between] weak civility, strong civility and pseudo-civility,” Ortiz said. “Weak civility is this idea that conversations should always be polite. … Pseudo-civility is when you shut down a conversation in the name of civility … [for example,] you just said something that’s out of line, so now we need to stop this conversation. And then strong civility is recognizing when … it’s valuable to be uncomfortable when … my ideas are being challenged … and I need to actually listen to the other side.”

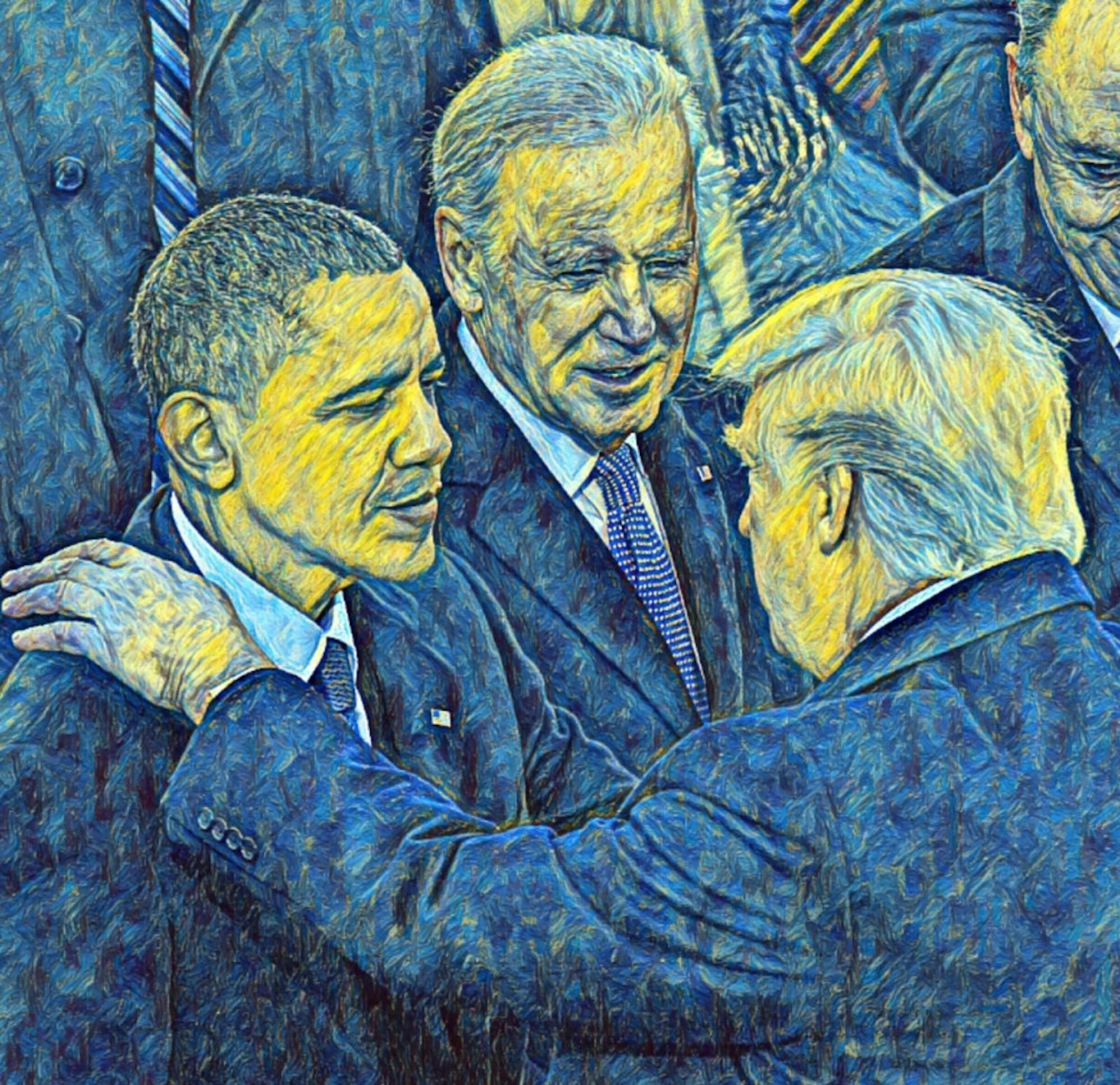

When students practice civility in contentious policy discourse, they are able to foster a greater mutual understanding that elevates their similarities on policies and values. Previous conversations surrounding climate change and reproductive rights between Tufts Democrats President Mark Lannigan and Tufts Republicans Vice President Trent Bunker illustrate this point. On both issues, Bunker and Lannigan expressed distinct policy differences. However, when it came to foreign policy, specifically on the Russia-Ukraine War, both expressed similar positions over the values and policies the Biden administration should pursue.

The Russia-Ukraine War, raging since February, has entered a new and perilous phase. 338 bodies have been exhumed from a mass grave site in Izium, with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky pointing to the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation as the culprits. At the same time, an illegal referendum conducted by the Russian government has enabled the government to annex eastern Ukrainian territory.

In light of the ongoing military crisis in Ukraine, Bunker was understanding of the Biden administration’s tough position in the war.

“I think that … [Joe Biden] is caught between a rock and a hard place, because … [there are] both of the extremes, you have the isolationists on the far-left and far-right, and then toward the middle. … You have people who are more willing to assist the Ukrainians,” Bunker said.

Lannigan expressed a similar sentiment about Biden’s position, referencing the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan and developing friction between Kurdistan and Tajikistan.

“The U.S. is going to be pulled in a lot of different places. At the moment, until I'm shown differently, I think [Biden] has been doing the best that he's could … in Ukraine,” Lannigan said.

Because of the Russian government’s violence in Ukraine, discourse has emerged over the future and expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a transnational military alliance established after World War II between European and North American countries, including the United States.

In this context, Lannigan voiced his support for NATO and noted the importance of the Biden administration maintaining the Trans-Atlantic Alliance.

“I think part of the strength of the Alliance is ensuring that we show up for the Alliance and we show it for [governments] who want to join the Alliance,” Lannigan said. “So definitely, it’s been good that [Biden] has been siding with [NATO].”

Along with Lannigan, Bunker expressed his support of NATO and emphasized the importance of other countries contributing more to the Trans-Atlantic Alliance.

“Part of the way that we can support this Alliance is … incentivizing other countries to get as involved into NATO as [the U.S. is] because … for better or worse, … we have been an exceptionally strategic partner,” Bunker said. “Maintaining our pledges to NATO is crucial … for preserving the international order. But at the same time, it also requires countries [in Europe,] who live on the doorstep of Russia, to reach a level of involvement … at least proportional [to their size and resources].”

From these conversations between Bunker and Lannigan, along with Hersh and Ortiz’s observations, a greater theme emerged. As American politics continues to polarize, it is particularly important to understand where others get their different perspectives from and understand the tenants and underpinnings of such viewpoints.

For Hersh, who is planning on teaching a course on American conservatism for the spring 2023 semester, it is critical to be exposed to new political perspectives, even if the initial experience is uncomfortable. For more progressive students, that means learning and understanding what conservatism is and how it manifests in politics.

“The reason why I want to teach a class on conservatism is I want … conservative students to be able to … craft their own identity, but I also want liberal students, or students who don’t know what [conservatives] think, to learn what they think,” Hersh said. “I wonder if students are interested in reading contemporary conservative thought and thinking about, ‘What are conservative perspectives on hot-button issues?’ … I hope there is an appetite for it … I think there is a lot of room for students to learn about what it means to be a moderate or a conservative.”

Echoing Hersh’s sentiment, Ortiz highlighted the importance of civic discourse in American politics going forward.

“This idea of citizenship and what it means to have a civic duty … there's like a very American element to that, that I think comes [from] people caring about local politics,” Ortiz said. “I think that’s how you can get people … more involved [in] politics and also involved in a positive way, where they are not just cheering on [their own side] … rather [questioning] what [we can] do to make our community better,” Ortiz said.