Editor's Note: “Ballou” in this article will refer to Hosea Ballou 2d unless otherwise specified. Tradition at this time was to use “2d” as opposed to “junior” or “II.”

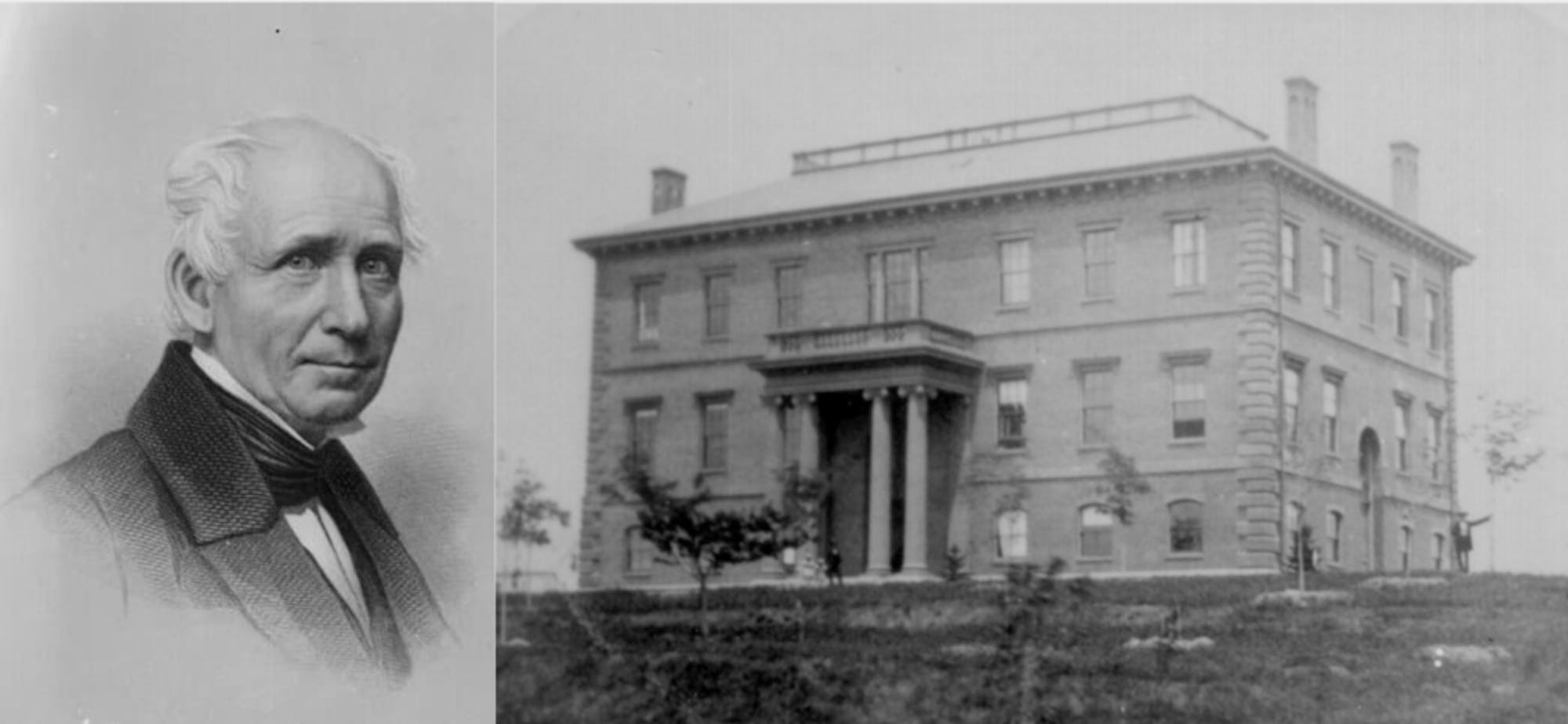

“TUESDAY, JULY 19, 1853, was a typically warm midsummer day in the Boston area,” Russell Miller wrote in his authoritative history of Tufts from 1852-1952, "Light on the Hill" (1986). “The location was Walnut Hill, on the outskirts of the town of Medford, Massachusetts; from this eminence, the highest in the Boston area, the Bunker Hill monument was clearly visible, and it was said that seventeen towns and villages could be distinguished in the distance. The occasion was the laying of the cornerstone of the main building for ‘a literary institution devoted to the higher cultivation of the mind,’ already christened Tufts College by its Board of Trustees.”

Even though Tufts College was chartered in 1852, students would not enter Tufts University's halls until 1854. This gave Rev. Hosea Ballou 2d, who was a pastor and had little administrative experience, ample time to embark on this mission.

Ballou was born in Guilford, Vt. in 1796 to a Universalist family. After receiving only a primary education — as traditional Universalists were wary of over-education — Ballou became a teacher, traveling preacher and recognized minister. After marrying his childhood sweetheart, Clarissa Hatch, in 1820, he served the parish of Roxbury, Mass. from 1821–1838.

“[His namesake, Hosea Ballou], great-uncle of the first president of Tufts (and often confused with him), has often been considered ‘the father of Universalism in America,’” Miller wrote.

During this time, Ballou, ever the intellectual, continued his learning with self-education.

“During the 1820’s he perfected his earlier knowledge of Latin, learned to read ‘with ease’ French, German, and Greek, and acquired ‘considerable knowledge’ of Hebrew,” Miller wrote.

During this period, Ballou also emerged as a writer.

“He contributed over 100 articles and reviews to Universalist periodicals, co-edited at various times two Universalist papers, edited a scholarly journal which he had founded, edited the first American edition of a European work in religious history, and published a collection of psalms and hymns for Universalist use,” Miller wrote. “His major research contribution was a history of Universalism during the first six centuries of the Christian era which probably did more than anything else to establish the author's reputation as a Universalist scholar.”

In 1842, Ballou joined the Board of Overseers of Harvard University, where he would serve until 1858. It was during his time at Harvard that Ballou got involved with the fledgling movement to create a Universalist school.

According to Miller, Universalism became a "recognizable sect" in America toward the end of the eighteenth century. "[Universalism] represented a small part of the larger movement of revolt against the Calvinist predestinarianism which the majority of colonists had inherited,” Miller wrote. “It offered, through its teachings of the universal Fatherhood of God and the universal brotherhood and ultimate salvation of all men, an optimistic, humane ethic characteristic of the democratic strivings of a new nation in the making.”

Universalists eventually developed a reputation for being outspoken on liberal religious issues. From the very beginning, the sect advocated for a separation of church and state.

“They took a strong stand against slavery, advocated temperance, and even organized a General Reform Association in the 1840's through which they could express themselves and act on the various movements permeating the Jacksonian era that were intended to better the lot of mankind,” Miller wrote.

The skepticism of traditional Universalists toward higher education had not been a problem when the sect was still emerging, but as it expanded, many began to call for more formal education for young men intent on entering the ministry. This had widespread support, but there was vigorous debate over how it should be done, specifically over whether the education should be purely theological, literary or a combination thereof.

Plans to establish a Universalist school endured many starts and stops, but eventually a Board of Trustees, which included Ballou, was created to oversee the project and bring it to fruition. Ballou was a natural addition to the Board, as he had contributed to the rise of Universalism in the country.

“Gentle and retiring to the point of self-effacement, studious and meticulously thorough, he was active, in his quiet way, in most Universalist affairs during the crucial early period,” Miller wrote.

One of the first orders of business was deciding on the school’s location. One option, Walnut Hill in Medford, was far from Ballou’s first choice, largely due to its proximity to Harvard University, as he explained to T.J. Sawyer, fellow trustee and even more prominent Universalist than Ballou.

“We shall at least stand before the public, in comparison with Harvard,” Ballou wrotein a letter to Sawyer. “The oldest, richest, best appointed University on this side of the Atlantic, which stands in plain sight, with its army of professors … to say nothing of its library, cabinet, scientific school, law school, medical school, etc.”

There was one benefit to the location, however, which appears to have trumped all other concerns.

“I know of but one reason for having the college in so unfortunate a position: a large sum, given by Mr. Tufts, is granted in condition that a literary institution of some kind, under the control of Universalists, be placed on Walnut Hill,” Ballou wrote to Sawyer.

When Charles Tufts was once asked what he planned on doing with Walnut Hill, he famously replied, “I will put a light on it.”

This land was not uninhabited before Tufts came into its possession, however. The campus sits on what was once home to Indigenous communities in Massachusetts before colonists appropriated the land.

“As an institution that benefits from the ownership of land once inhabited and cared for by Indigenous communities, Tufts has a responsibility to recognize this history and engage with the descendants and nations who represent the original peoples of what is now eastern Massachusetts,” Tufts’ admissions website says.

Along with Charles Tufts' donation, Universalists who were overjoyed at the news of such an institution also contributed small donations that formed the backbone of Tufts’ initial funding.

“There was just this groundswell of excitement, enthusiasm, putting people's resources into this enterprise — really putting their money where their mouth was — to build this thing,” Pamela Hopkins, Tufts public services and outreach archivist for digital collections & archives said.

The presidency was originally offered to T.J. Sawyer, who declined. Next on the list was Ballou, despite his hesitancy toward the idea.

“He deeply wanted the college to be established and to be successful,” Hopkins said. “But he had no desire to be its president. And he, of course, had no experience being a college administrator.”

"You will think me very presumptuous in undertaking the office of president, and I perfectly agree with you therein. But I shut my eyes to the consequence, and rush forward."

Hosea ballou 2d, 1853

Ballou’s surprise at his own decision to accept the offer is evident in correspondence with his brother Levi.

“I suppose you have heard that the Trustees of Tufts College have ventured the hazardous game of appointing me president,” Ballou wrote. “You will be still more surprised to learn that I think of accepting the office, — not on the ground of being fit for it, which the Lord knows I am not, but because I do not know who they can get that is fit for it […] You will think me very presumptuous in undertaking the office of president, and I perfectly agree with you therein. But I shut my eyes to the consequence, and rush forward.”

Ballou had one caveat to accepting the position; he required a year to visit a variety of colleges in order to “to get some idea of what a College is,” as he put it in the letter to his brother.On Sep. 20, 1853, Ballou started this process at Harvard University, somewhat ironically.

Next up was Williams College on Nov. 8, 1853, Yale University (then College) on Nov. 14 and Brown University on Dec. 5. According to Hopkins, he also took the search abroad, spending time in Europe to observe how higher education was conducted there.

Further taking matters into his own hands, Ballou sent out a general request to Universalists everywhere to help supply Tufts with books.

“All the Universalists are just so excited about this enterprise and are contributing financially and fundraising and trying to send books and the whole bit,” Hopkins said.

These books would have gone directly into the hands of Tufts’ first students and to Ballou’s personal library, which served as the school library for some time. Ballou’s collection is now housed in the Department of Special Collections at Tisch Library.

Once the school was nearly up and running, Tufts’ supporters were given a taste of what their work had helped create. A course catalog of sorts — containing the College’s Board of Trustees, faculty, admission information, courses of study and expenses for the 1854–55 school year — was distributed to churches, peer institutions and individuals to begin the process of enrolling students.

“Those [first] students are taking something of a leap of faith,” Hopkins said. “They're really trusting that this is something that will be lasting, that if they all work hard — and with the providence of God and His care — they will have this successful college that will continue to bring up young clergymen and educate them in the liberal arts tradition.”

The catalog reveals stark differences between the fledgling institution and the Tufts of today. Although more limited than at present, course subjects ranged from ancient languages and rhetoric to hygiene and moral science. Ballou himself was the instructor of history and intellectual philosophy and also served as the university's librarian and administered religious services.

The admissions process did not include SAT scores, high school transcripts or essays, but simply that students “produce certificates of their good moral character” and pass examinations in Latin, Greek, mathematics and history.

Student expenses were even further from those of today, consisting of $35 for tuition, $10 to $15 for room rent, $5 for library use and $2.50 for board.

The student body, however, appears to have had much of the same energy Tufts enjoys today.

“Student wacky hijinks started right away with broken windows, where things just kind of get out of hand,” Hopkins said. “There's a lot of high spirits early on. And we see this very early initial growth and presence of a robust and developing school spirit in the student body.”

Ballou died in office in 1861, leaving behind an institution that would thrive on the seeds he sowed. While it eventually shed its Universalist focus, Tufts has never strayed far from the spirit that was established in those early days.

“I don't think he could have, over 150 years [later], imagined where things would be now, but there's some really sturdy foundations built on that hill,” Hopkins said. “I see this long thread of that can-do attitude through Tufts all the way to the present day, that if we work hard, and we maintain our values, and we push for justice … we're gonna get there, in the end — that all our sacrifices will be worthwhile.”