As he began to stream at 8 p.m. on Thursday, June 4, Stephan Pennington cautiously set a $500 fundraising goal for himself. When he signed off his computer in the wee hours of Friday, June 5, he had raised over $10,000 to support bail funds through The Bail Project, a nonprofit that works to end the bail system by paying bail for low-income Americans and advocating against pretrial incarceration. Over the coming days, Pennington’s fundraising total increased to $12,600.

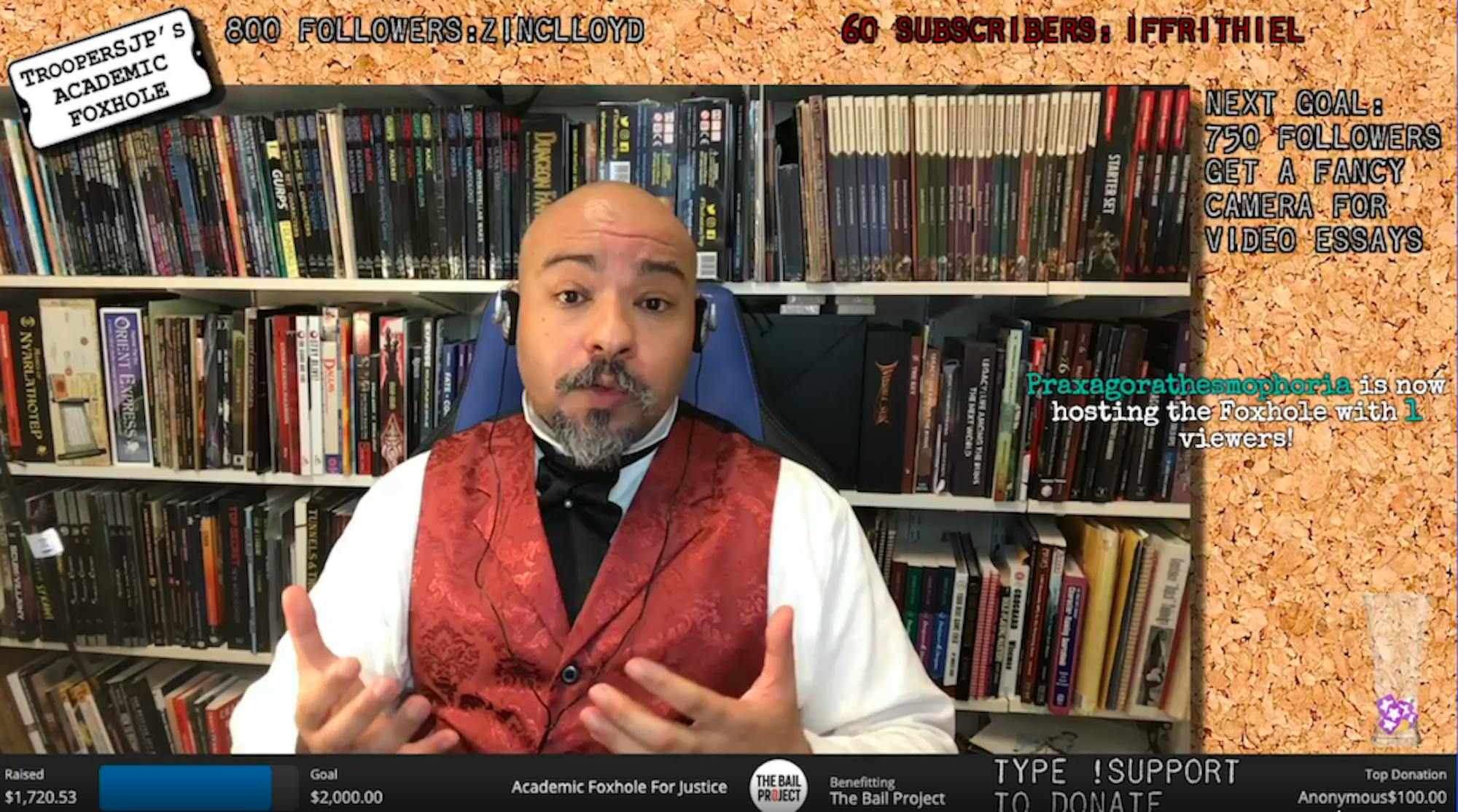

During the day, Pennington is an associate professor in the Tufts music department. At night, he is TrooperSJP, his “stream name” on the popular streaming platform Twitch, where he shares his video game screen with his 20–30 viewers.

“I have always played video games … since I was a kid, since Pong,” Pennington said. “But since I got to Tufts, I realized I wasn't playing video games anymore because I was just always so busy. I never made time for free time.”

As he realized that, Pennington began to watch video game streams online and discovered that one streamer he liked was a grade school teacher.

“Well, if she can stream and it's not a problem, then I could probably stream and not get fired. I could maybe do that,” he thought to himself. With that, Pennington began to set aside time each week to stream, playing mostly indie and role-playing games.

He built up a small following along with a network of other streamers, and as protests against racism erupted nationwide over the summer, Pennington asked himself what he was doing as an activist. When he saw that a streamer colleague was leading an effort to raise money for bail funds, he knew he wanted to participate but wondered whether he could do something unique, rather than doing a regular stream and asking for donations during it, as other streamers had done.

“I really wanted to do something that would be valuable,” Pennington said. “Maybe I’ll adapt a couple of my lectures from the History of African American Music [course] and I’ll do a charity stream where I do that … I thought, if I do the stream, people who can't go to Tufts can get access to it, so I'm actually doing an act of public education, which I think is in itself a form of activism.”

Pennington distilled about five lectures from his course into a four-hour lesson specifically covering Black protest music in the United States, from the Middle Passage until today. He invited both members of his academic circles — many of whom had to learn how to use Twitch for the first time — and streaming world, something he had never done before.

The songs he discussed are at times painful, raw and haunting, while others — though sometimes the same song — are empowering and unifying. Throughout the lecture, Pennington offers commentary, context, analysis and thought-provoking questions, seamlessly transitioning from reading and monitoring the live chat to explaining the history of a song to closing his eyes and silently air drumming away as a song plays.

During a particularly emotional moment almost three hours into the stream, Pennington received an anonymous $1,000 donation that pushed him over his $7,000 goal (the goal changed throughout the night). “We did not! What? Did we make goal? Oh my goodness. Oh my goodness … I am going to keep doing this talk so I don’t freak out and cry,” he said, looking shocked. Despite his best attempts, he could not hold back his tears, and it’s easy to imagine many of his viewers reacted the same way.

TrooperSJP, Pennington’s stream name, draws on different parts of his life that brought him to his work today; SJP are his initials, but trooper refers to his experiences both in the military and in theater — trouper is another term for actor.

“I started as a kid doing musical theater, and theater in general, and I wanted to do acting [professionally]. I wanted to do Shakespeare, but I could not afford to go to college, so I joined the army in order to pay for college and … did military intelligence,” Pennington said.

After earning a 2.87 GPA in high school, Penningston discovered he was skilled at “school stuff” while working in intelligence for the military.

At the same time, he branched out from his roots in musical theater to music more broadly by joining a rock band in the army. When he was acting, Pennington had to turn into someone else. Singing, on the other hand, let him become a fuller version of himself.

“When I got more into music, I was like, ‘I can sing what I want. I can sing the songs that I want, how I want them,’” Pennington said.

In light of this newfound space to express himself, Pennington decided to return to civilian life and study music performance and composition as an undergraduate.

Encouraged by one of his professors and the realization that he would not have to pay for a Ph.D. but instead be paid in the process, Pennington went on to pursue a Ph.D. in musicology at the University of California, Los Angeles. Studying music academically, he discovered that much of what resonated for him personally was also what made music meaningful professionally. Just as music offered him a way to express himself, it had also been a way for everyday and marginalized people to express themselves throughout history.

“You remember when you were in middle school, and they're teaching you world history, and it's this king does this and this general does this … and on and on for a while?” he asked rhetorically. “I remember thinking, what were poor people doing in ancient Rome? No one ever talked about what everyday people did.”

Though he was often told that these records didn’t exist, he thought to himself, “If I [want] to know what [a] marginalized person … did, I’m probably not going to find it in history books, but I probably will be able to find it in art.”

Pop culture became Pennington’s window into the lives of regular people throughout history and his vehicle for telling their stories. These questions have carried Pennington until today. He teaches courses at Tufts such as Queer Pop, History of African American Music and classes about the history of other marginzalized groups in music. Because his teaching leaves him with only limited time for other work, Pennington is taking a year-long research leave from Tufts this year to work on a book about transgender musicians over the last roughly 100 years.

When Pennington, who is Black, thought about his fundraising stream and Black people in America in the present moment, he considered how racism and the marginalization of Black and other minority voices persists.

“When the coronavirus started, I didn't have any masks,” he said. “But I had a bandana, and I put on my bandana to go to the pharmacy in Davis Square. I walked into the [CVS Pharmacy] wearing this bandana, and I thought, ‘Oh, gosh, what if they think I'm going to rob this place? What if somebody calls the cops and somebody shoots me?’ And every time I walked outside of my house with this bandana on, that's what I thought. And I just didn't leave. I just didn't leave campus. I did not leave my house. I left my house probably five times total since March, because it was too unsafe.”

Despite this fear, Pennington says the world is changing. Unlike during the protests in Ferguson, Mo. in 2014, now, his friends are checking in on him to see if he is doing OK in these difficult times. One friend even made him a “super cute” mask to make going out in public safer.

“My mother had to drink at the colored watering fountain when she was a little girl. And I am not old … that is not the world we live in right now. I'm not saying it's great. But I'm saying that we have changed so much and we changed because we didn't stop,” Pennington said.

“You have to keep your motivation up, you cannot allow yourself to be so disheartened that you stop pushing, because then change doesn't happen. But change can happen.”

Weeks after raising thousands of dollars for bail funds, Pennington is still stunned by the impact he personally has had. “We ended up with $12,600. That is not a number that I ever imagined. That's unrealistic, an unrealistic amount of money to think about. I never imagined that that would happen. Like, what is that? That's a bunch of madness.”