Some Tufts students have a light Friday schedule to start the weekend, but not sophomore Mrugank Bhusari, who starts his Friday with classes from 8:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. This leaves him with just enough time to pick up a quick lunch from Hodgdon Food-on-the-Run before an afternoon shift at his work-study job with the Institute for Global Leadership (IGL) until 5 p.m. By the time the day ends, Bhusari is exhausted.

"I feel kind of drained," Bhusari said. "I have less energy ... to do other things [throughout the day]."

Bhusari is not alone. In an email to the Daily, Patricia Reilly, director of financial aid, said about 1,500 undergraduate students, or about 27 percent of the student body, have work-study as a component of their financial aid packages.

"When we determine financial aid, we assume that in addition to direct costs for tuition fees, room and board, students will have indirect costs such as books, supplies and personal expenses. Work-study allows students to earn money to cover these out-of-pocket expenses," Reilly said. "[All] work-study earnings are paid directly to students — they do not get credited to the student account and are not used to pay the Tufts bill."

However, a quarter of undergraduate financial aid recipients are not eligible for work-study, Reilly said. These include students who have "outside aid awards or special scholarships" which replace the work-study component, or students who are unable to work for various reasons, according to Reilly.

Tufts also offers its own work-study subsidy to a small number of students who do not qualify for the Federal Work-Study program, including international students like Bhusari. However, Bhusari said that he faced greater difficulty in finding a work-study job as an international student on a visa.

"First I have to see whether I can apply for this [job] as a non-American citizen," Bhusari said. "I have work-study, but I don't know where to avail those [funds] because I cannot work off campus, so I have to work on campus."

In addition to his current position at the IGL, Bhusari also works as a research assistant to Justin Hollander, a professor of urban and environmental policy and planning. In total, Bhusari works on average eight to nine hours a week.

"As a research assistant ... the hours aren't certain, so I don't know how much I am going to work every week," Bhusari said. "With the IGL, it's more consistent — I will be working these many hours so I will be getting paid for these many hours."

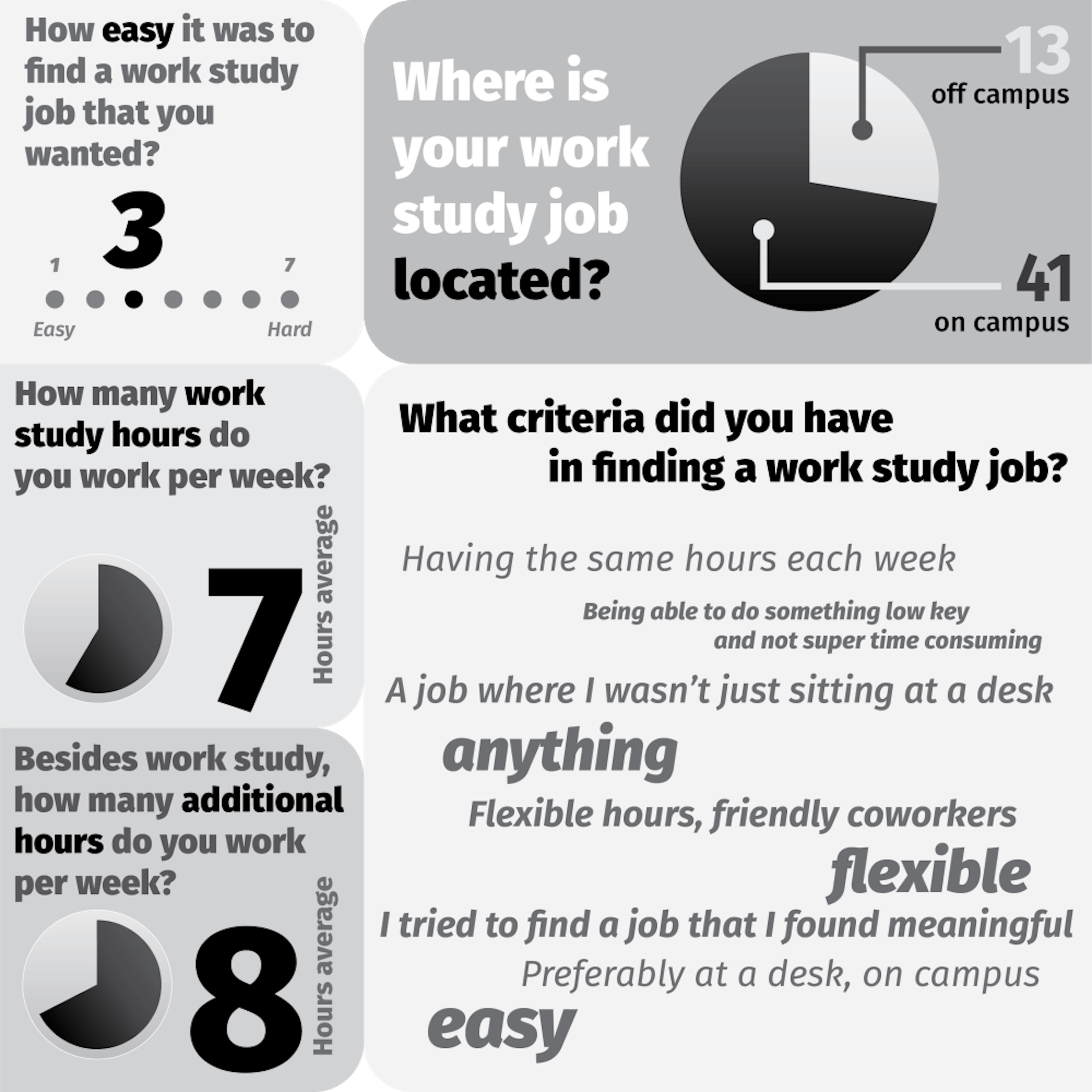

Of the 76 students whom the Daily surveyed in February, 54 had work-study jobs, and these students worked an average of seven hours a week, with 12 students working 10 or more hours a week.

The Daily's survey also asked students to rate the difficulty in finding a work-study job that they wanted — on a scale from one to seven, with seven being "extremely difficult." The average rating was three.

Bhusari found the process of searching for a work-study job in his first semester at Tufts to be challenging.

"It's ... frustrating that there has to be so much effort to find a job, because it's part of your aid package. So it's expected that you will be earning [the income], but there's no readily-given provisions to find those kinds of opportunities," Bhusari said. "[I had to] ask people if they knew that there were jobs at their workplace, maybe [to] help me to talk to the manager."

In the end, Bhusari was able to find his current work-study jobs by being in the right place at the right time. He took a class with Hollander in his first semester and was hired when a research assistant position opened up in the semester after. He found out that the IGL was hiring for student workers through enrolling in the IGL-organized Education for Public Inquiry and International Citizenship (EPIIC) colloquium.

"I wasn't expecting [the positions]," Bhusari said. "It was more by luck and connections."

Like Bhusari, first-year Hasan Khan found his work-study job through an unexpected opportunity. Khan was invited last summer to apply for a work-study-eligible position in the Student Communications Group, which produces multimedia content for the Tufts Office of Undergraduate Admissions, and was successful.

"I just happen to be very lucky; I managed to get a job that was eligible [for work-study]. If I hadn't done that, I would have been probably very lost in the beginning [of the school year] and then also have to start the work-study process pretty late," Khan said.

With this position in the admissions office starting immediately in the fall, Khan was able to earn the full work-study income for which he is eligible.

"If I didn't start when I did, like, from the beginning, working through my job that I already had, then I might not have made [the full work-study] amount," Khan said.

Khan knows of fellow first-years who had work-study as part of their financial aid package but were unable to find a work-study job until much later in the year.

"One of my good friends got her [work-study] job in late November. Some people had difficulty starting their job because it was late enough in the semester [when they found their job]," Khan said.

Khan noted that student difficulties in finding a work-study job early in their first semester of college may stem from not having a thorough understanding of the details of the work-study program, such as what jobs are eligible and where to find them.

"As a student being admitted, and finally seeing my financial aid package, I had no idea really what [work-study] was, what that would mean or what that would look like," Khan said. "It sounds like a job, but ... over the summer, I thought — before I got the job — I was going to be assigned a job," Khan said.

Bhusari echoed these sentiments, adding that part of his confusion also stemmed from being an international student who was unfamiliar with how college financial aid worked in the United States.

"I saw work study as a [part] of my aid package, and I had no clue what that meant," Bhusari said. "I didn't know if I would get paid for working or if I had to work as part of a program — it was really unclear. And so, when I came [to Tufts], the first thing I found out that I didn't have to ... work as part of a program without pay. That is what I first thought it meant."

Both Bhusari and Khan work on campus, where most work-study jobs are located. Reilly said that the majority of on-campus work-study jobs have traditionally been with employers such as the libraries, the Tisch Sports and Fitness Center and Dining Services, with "a small increase" in jobs in other areas such as research or tech support with Tufts Technology Services.

Besides working on campus, Reilly added that in 2017–2018, 140 students earned their work-study through the America Reads Challenge program with Tufts Literacy Corps or Tufts' Jumpstart chapter, and 50 students earned their work-study at jobs in nonprofit organizations in the community. The Daily also found that 13 of the 54 work-study students surveyed said they work off-campus, including senior Jason Theal.

Theal currently works about eight to nine hours a week as an after-school homework helper for Tufts Literacy Corps, which he has been a part of since the fall of his first year.

"I have an affinity for reading and literacy, so I thought it would be perfect," Theal said. "I greatly enjoy reading myself, and it has been a personal project for me to help as many kids as I can to try and discover a joy for reading, or at least ... see it as less taxing and troublesome as students sometimes feel, especially moving through middle school and high school, where it's just a lot of reading."

Theal said that planning his schedule to fit both work and school can be taxing. The days when Theal is needed at work and the schedule for the classes that he needs for the geological sciences major are fixed, and he is fully occupied for the entire duration of his work.

"The span of hours can be difficult to manage, because you are giving up a good portion of your afternoon to working with the kids, and, although rare, you can work [on] your own homework if the kids don't have any homework, but that is not helpful to the kids and it's not often enough to be counted on. So often, no homework gets done," Theal said.

At the moment, Theal is not working any other jobs, but he has worked as a shelver at Tisch Library in the past.

Of the 54 students the Daily surveyed who indicated that they had work-study jobs, 18 students said they work additional hours — an average of eight per week — outside of their work-study jobs.

Reilly said that students' non-work-study jobs or other on-campus commitments may affect how much of their work-study awards they choose to use each year, adding that in 2017–2018, about 40 percent of work-study students earned at least 80 percent of their work-study award.

While Theal had "no major complaints" about his work-study experience so far, he sounded a note of caution against exceeding one's work-study award.

"I, without realizing, had worked more hours than my work-study money was able to pay, and so I ended up running out of money to pay for my hours around early April. I ended up still going to work ... but I wasn't paid for [those hours], which was frustrating at the time," Theal said. "It ended up causing a little bit of consternation on my part because I didn't know it was about to happen, and I would have tried to alleviate the problem beforehand."

Bhusari acknowledged the annoyance that other students may express at on-campus employers who would only hire students who are eligible for work-study, but noted that the income from a work-study job is necessary for students like himself to get by.

"From the perspective of the students who are getting those jobs ... I don't want to work 10 hours a week," Bhusari said. "If someone else wants a job, I don't want to take the job. It's just that I need money, and I think that idea is not understood completely across everyone."

Work-study students balance commitments, find financial security