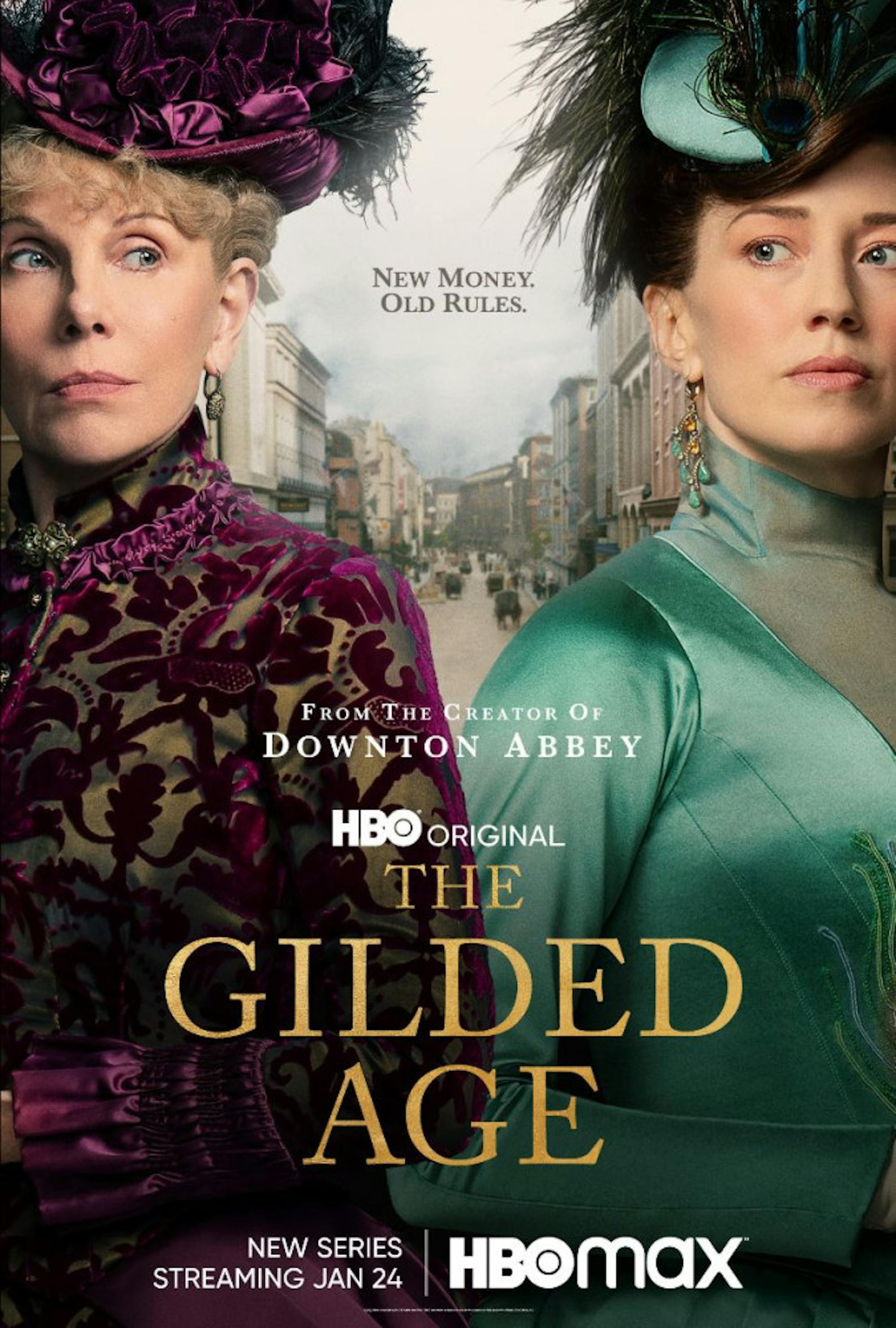

The period piece is a fundamental staple within modern media. It’s riveting to be transported back to another age, to see the flourishes of the lifestyles and to identify the predecessors to our modern actions. Still, the genre’s impact would be fairly minimal without the contributions of a leading figure, creating the landscape and driving a television empire: Julian Fellowes. Fellowes created the iconic “Downton Abbey” (2010–15), a British historical melodrama that received widespread critical acclaim and a cult following. Fellowes returns to the television scene with “The Gilded Age” (2022–), bringing the same period allure to a new American setting. The new series may not have a broader significance to the culture or community ideals, but it succeeds in providing what “Downton Abbey” provided for so many: simple, enjoyable television.

The show sets itself in 1880s New York City, deep within the rapid growth of the American economy and technological innovation. It follows a dueling set of neighbors: the old-money Ada Brook (Cynthia Nixon) and Agnes Van Rhijn (Christine Baranski), and the new-money George and Bertha Russell (Morgan Spector; Carrie Coon). The show begins with Marian Brook (Louisa Jacobson) moving in with her aunts Ada and Agnes, shifting from the simplicity of Doylestown, Pennsylvania, to the complex social politics of New York City. The viewer follows Brook as she moves through the city, making friends and falling in love, and surely disobeying her Aunt Agnes’ insistence not to mix with the lowly new-money individuals along the way. The show is about high-class drama and living and about how the elite may both present their utmost humility while sowing strife along the way.

Ultimately, the show is perfectly bingeable television. It is high in drama, allowing for intrigue and a continued focus throughout the progression of the show. Still, the show maintains incredibly low stakes, making the viewing experience almost entirely stress-free. No matter the outcome of these proliferating social squabbles, all will be deeply comfortable within their own wealth. No choice made will have life-altering consequences. In fact, the show even presents an exemplar of someone whom the social tide has turned against, in the form of Mrs. Chamberlain (Jeanne Tripplehorn). Mrs. Chamberlain was cast out of civil society after the death of her husband but still lives a beautiful and well-off life. Thus, even if a favorite character receives a twist in fate, putting them in dire straits, they will maintain their comfortable wealth. It is this sense of low stakes that makes the show deeply pleasant and gratifying.

The show is also a fascinating ‘who’s who’ of the broader theater scene, with a multitude of parts pulling big names on Broadway. The show gives theater actors the opportunity to shine on the screen, such as Denée Benton, known most for her performance as Natasha in the musical “Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of 1812” (2016). Benton gets to take on the leading role of Peggy Scott, a newfound friend of Marian’s who helps her with train fare after her ticket gets stolen. Keeping within this theater community, Scott’s mother is played by Broadway legend Audra McDonald. Even the smallest parts pull common faces in theater, like Celia Keenan-Bolger, the original Olive in “The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee” (2005), starring as one of the servants to the Russell family. This cast of prominent theater actors provides a fun Easter egg, forming the show into a persistent IMDb. When you think ‘Oh I know her, where do I know her from?’, the answer is probably the theater.

Still, it must be noted that the show does nothing truly revolutionary or impactful. It fails to provide any significant critical commentary on present-day issues, making the sense of urgency and meaning somewhat limited. The show tried to do this — creator Julian Fellowes introduced racial diversity to the show in the form of Peggy Scott and her family, presenting not only Blackness but also an image of Black wealth and joy, something broadly underrepresented in modern media. This contrasts with “Downton Abbey,” which was almost entirely a story of whiteness. Still, these attempts at social relevance are ultimately futile: The show presents itself in the same way and tells the same story. It is not a helpful commentary to our modern political dialogue. Still, that may be okay for one show. Though we should be desiring our media to be representative and encouraging of socially optimal outcomes, there may be a space within the market for simple, watchable television. That is what this show is — certainly not pushing for progressivism but rather not pushing for much of anything at all. That neutrality may be a fault to some but a benefit to others.

Ultimately, “The Gilded Age” functions just the same as the iconic “Downton Abbey”: It draws the viewer in with its high-drama, low-stakes tension and provides a simply pleasant viewing experience. Thus, it’s difficult to rave about the mass benefits of the show — it clearly does not reinvent the wheel. Rather, it provides a brief and relaxing respite of entertainment, one that many audiences may be seeking out.