Content warning: This article discusses PTSD, abuse, trauma and antisemitism.

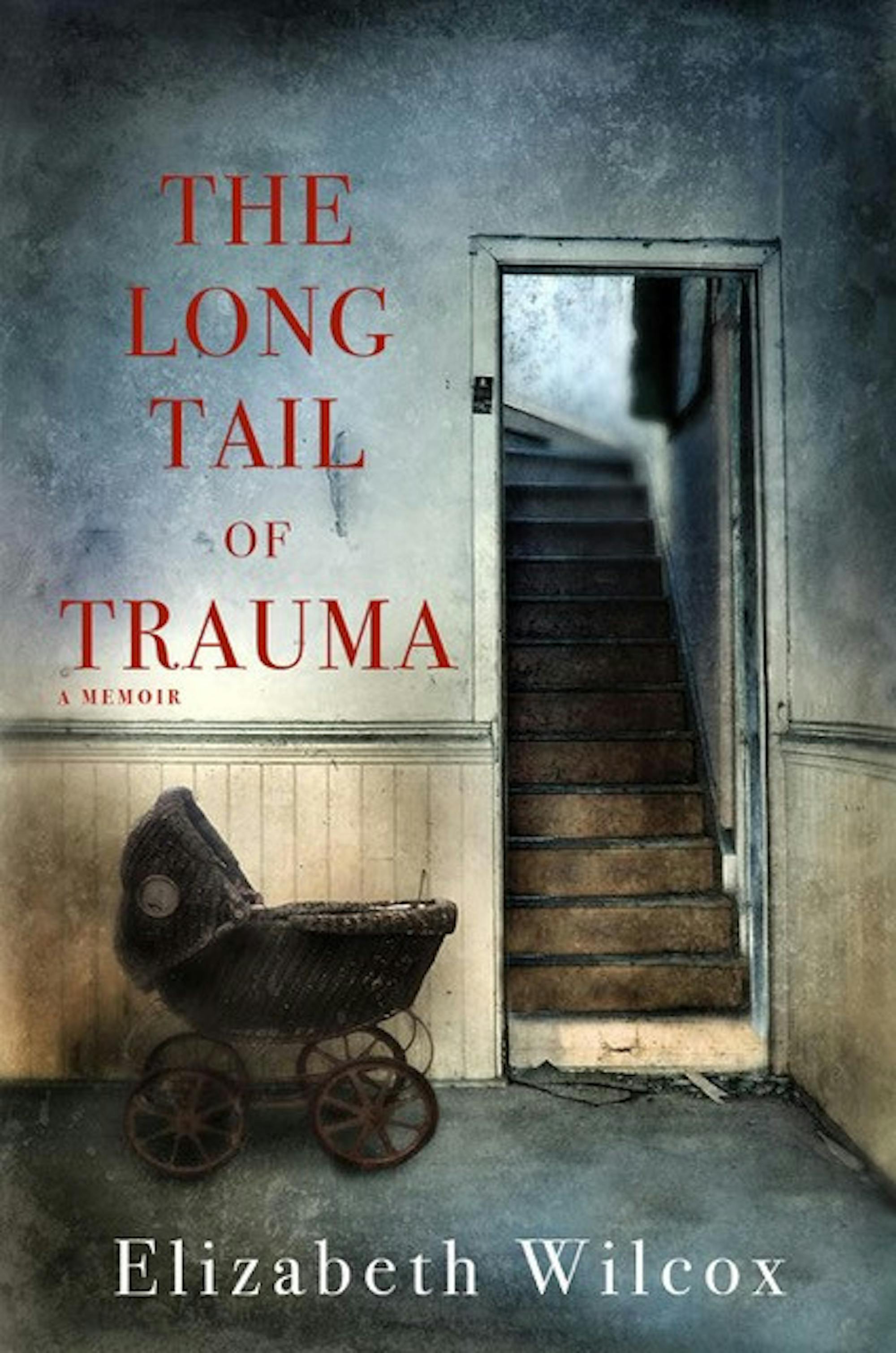

Brookline Booksmith hosted a conversationon Nov. 12 with author Elizabeth Wilcox and Dr. Bethany Casarjian that skillfully combined the commentary of Wilcox on her book "The Long Tail of Trauma" (2020),released Nov. 11, and the expertise of clinical psychologistCasarjian. The two women revealed the importance of talking about multi-generational trauma, specifically that experienced by women. As a result, victims can heal through developing relationships in the face of trauma produced by the lack of or acidity of past ones.

Wilcox initiated the event by explaining the complexity of her story. The book is part historical narrative, detailing the ordeals Wilcox’s maternal ancestors endured. The book begins with the birth of her illegitimate grandmother Violet, who was separated from her family and placed under the care of aunts. At the age of 6, Violet’s mother Anna reclaimed her, and both lived in poverty in London. Violet’s comfortable life with her aunts starkly contrasted with her menial life with her biological mother. This combined with other obstacles faced in a grueling adventure to avoid the consequences of anti-Semitism and the second World War exemplify Violet’s trauma-full life. Wilcox’s mother Barbara was separated from her mother Violet at age 3 as a part of Operation Pied Piper, the evacuation of English children from war-stricken London. Consequently, Barbara lived in abusive foster homes, lacking any wholesome parental guidance.

Wilcox defined the trauma of her maternal ancestors as adverse childhood experiences (ACE).Casarjian talked about this issue in relation to her work as the clinical director at the Lionheart Foundation, which partly aims to provide emotional literacy programs for traumatized youths. She shared a chart from the CDC demonstrating that ACE is influenced by the consistent historical trauma that burdened Wilcox’s ancestors. Most notably, Casarjian identified the level “Adoption of Health Risk Behavior” located towards the top of the pyramid. The most drastic effect of ACE is a shorter life span; yet, she emphasized that this correlation is the effect of damaging relationships with substance abuse and high risk behaviors. Still, Casarjian juxtaposed this chart with a hopeful quote from Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung: “I am not what happened to me. I am what I choose to become.” She explained that in the face of adversity, perseverance and success is still possible.

Wilcox supported Casarjian's previous fact with more details about her characters. Most specifically, Wilcox delved deeper into the second part of her book, which is a conversation between her and her mother as they discover she is suffering from PTSD as a result of ACE. Despite the trauma she endured as a child, Wilcox’s mother raised seven children. This feat highlighted her incredibly heroic strength, as her own parents were absent to model ideal parenting.

Casarjian also identified alloparenting as a key rehabilitative response to abuse. Alloparenting occurs when other individuals step into a neglected child’s life and provide parental care. Neglect is as toxic as physical abuse, and the absence of connectedness harms the brain. Referencing her work with the Lionheart Foundation, she explained how social-emotional training for staff enables them to coregulate better with the youths they work with. When a young person senses safety with the people aiding them, their brain is open to learning and healing.

Although Wilcox did not identify a parental figure who helped her mother, she described her father as beneficial for her mother’s emotional competence. Additionally, Wilcox’s relationship with her mother helped them both develop past the trauma layered in their systems. She recalled a scene where she fought with her mother in a car ride. Wilcox’s husband convinced her to return and fix the relationship.

Wilcox summarized her book as a story about mothers and daughters and the trauma they carry together. Her conversation with Casarjian revealed that maternal relationships can be neurologically painful, but also that these connections as well as others are most influential on the path to healing. The courageous role of a mother with an iron will to provide for her daughters is a potent love capable of reversing layered abuse.