Content warning: This article mentions addiction and substance abuse.

Following a genius obsessed with their craft is no new premise for television or film — much to the contrary, it’s proved itself a recurring formula for success in “Black Swan” (2010), “Whiplash” (2014) and “Birdman” (2014), just to name a few. Netflix’s miniseries “The Queen’s Gambit” (2020)is no exception. Impressive in its own right, "The Queen's Gambit" adopts a fresh perspective by delving into chess’ intersections with substance abuse and gender discrimination.

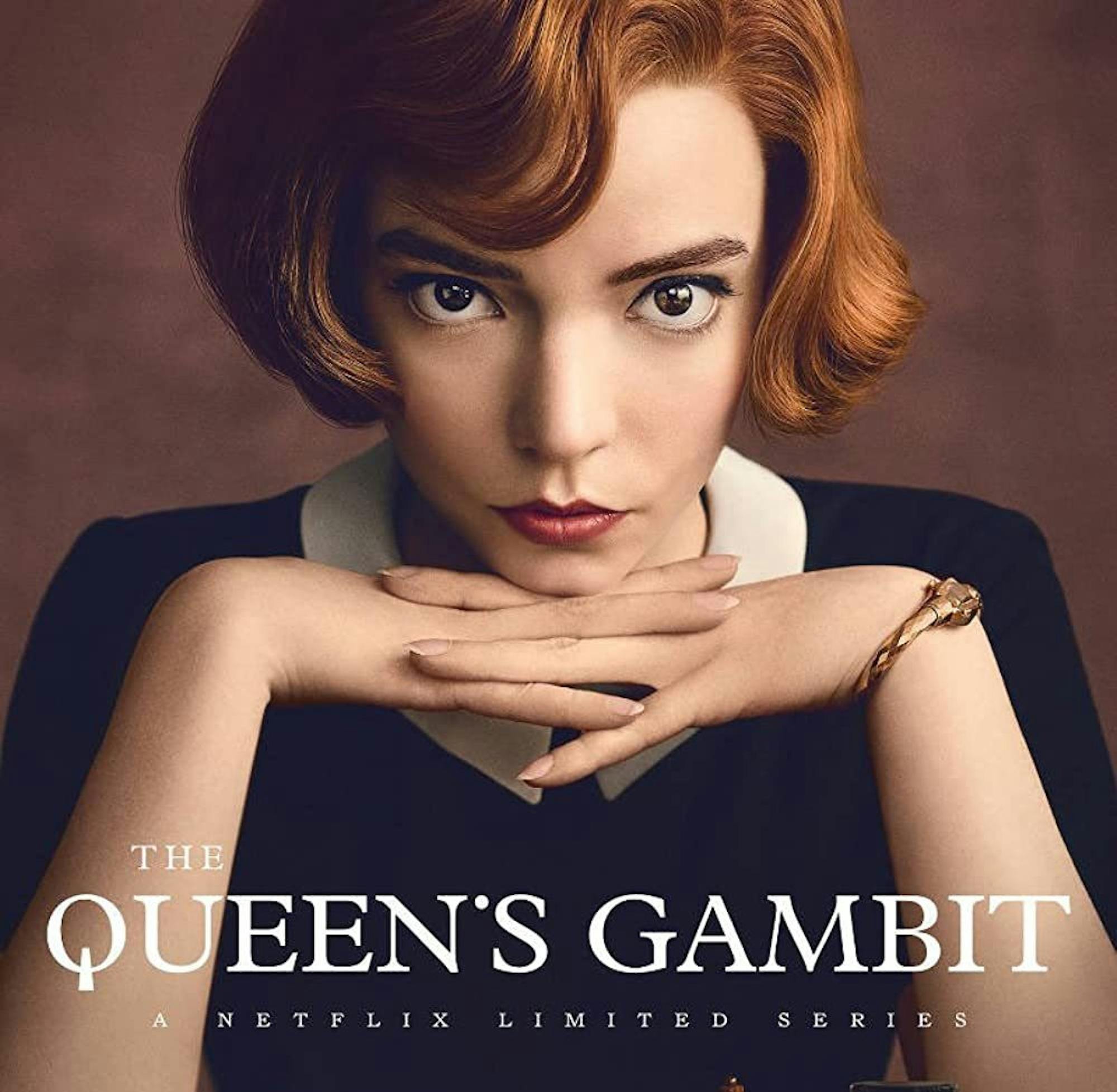

The show follows Beth Harmon (Anya Taylor-Joy) from the car accident that leaves her orphaned at the age of nine to her rise to world fame as a master chess player. Despite its fictional plot adapted from the 1983 novel of the same name by Walter Tevis, "The Queen's Gambit" has beenapplauded for its accurate depiction of competitive chess. It even references real players and games from the 1950s and 1960s and tackles the male-dominated nature of the sport by placing a female prodigy at its center.

From her first tournament, Harmon is unapologetic in defying expectations. Her geeky awkwardness starkly contrasts other girls at her high school who seem to prioritize shopping and social clubs over all else. However, it is Harmon’s glamorization as she rises through the ranks of chess that most juxtaposes her male-centric environment. While her ugly duckling to swan trajectory feels a bit exaggerated and trite at times, it challenges the assumption that her femininity should prevent her from belonging in competitive chess. With her luxurious coats, collared dresses and elegant headscarves, she stands out from a crowd of drab suits in the best way possible. Thanks to stellar costume design, her outfits are authentic to the period, but simultaneously so timeless.

Beyond pretty clothes and chess sets, the show explores more serious substance abuse and mental health issues. Harmon, played as a child by Isla Johnston, first becomes hooked on tranquilizers after receiving them at her orphanage — one of the most memorable scenes occurs when she steals more at the end of the first episode. While everyone is distracted watching the movie “The Robe” (1953), 9-year-old Harmon breaks into the pharmacy and downs handfuls of pills. With eerie, angelic music playing, her footage is interwoven with the culminating movie scene, where a woman requests to be executed along with the man she loves believing that they’ll enter the new realm of heaven together.

Similarly, Harmon’s action catapults her into a new stage of dependency from which she won’t easily be able to turn back. Like the woman who dies for her love, Harmon is enamored by the substances which will be the source of her undoing for the rest of the show. Addiction directly collides with her chess obsession, as she gets high just to spend hours mentally playing through games.

Interestingly though, unlike other works which study the self-destructive aspects of perfectionist obsession, mental health and substance abuse issues extend beyond the protagonist to other characters. This goes for both Harmon’s adoptive mother Alma (Marielle Heller)and her birth motherAlice (Chloe Pirrie), pointing to possible biological and social factors for Harmon’s difficulties beyond her genius. In fact, just as Harmon struggles as a woman in chess, these other women’s mental health and addiction issues are fueled at least in part by gender discrimination. Alice’s husband seems to give up and leave when he doesn’t know how to deal with her mental health issues. Alma experiences an existential crisis about becoming a housewife instead of following her dreams to become a concert pianist after her husband leaves her.

Furthermore, flashbacks of Alice struggling as an independent woman begin most episodes, framing Alma and Harmon’s similar struggles. Episode Five begins with an especially intense shot from young Harmon’s perspective looking up while Alice firmly tells her that she will need to learn quickly how to survive on her own in the world. Indeed, Harmon soon has to grow up without her birth mother, and this memory prefaces the episode where she must learn how to survive after her adoptive mother dies, too. By showing the legacy of women persevering in a man’s world behind Harmon, the series portrays her issues as much more complicated than the destructive side of genius. In light of this intergenerational gender oppression, her obsession with overtaking the male-dominated chess world takes on a new level of meaning.

The show becomes less effective when it focuses too heavily on particular chess games, losing sight of their connection with Harmon’s more complex struggle against addiction and sexism. These scenes drag on and become repetitive over time. The ending also feels far too clean to resolve the complex struggle for which the show laid so much groundwork. With that said, "The Queen's Gambit" is still worth noting for how it carries on — and adds deeper commentary to — the destructive genius theme of previous works.