Brookline Booksmith, an independent bookstore in Brookline, Mass., started a transnational literature series in 2018. This series was created to bring in books, authors and translations that explore borders through their work.

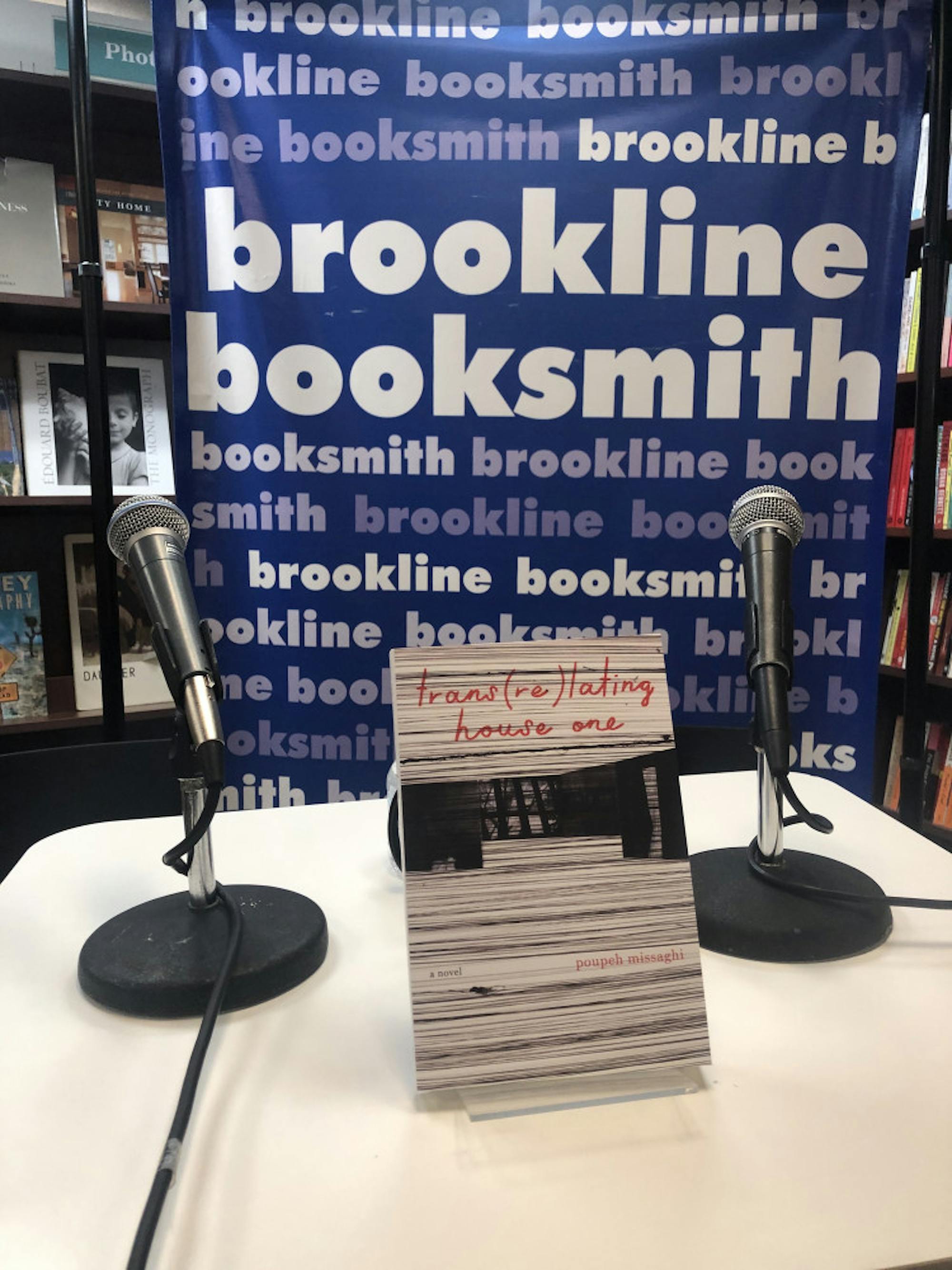

Poupeh Missaghi and her novel “Trans(re)lating House One” (2020) were featured on Feb. 12 in Brookline Booksmith’sused book cellar. The crowd itself was diverse, with different languages being spoken and a large Iranian presence as well. Missaghi is an Iranian writer, translator and teacher with a Ph.D. in Creative Writing from the University of Denver and an M.A. in Translation Studies.

“Trans(re)lating House One” is Missaghi’s first novel. It takes place in the aftermath of Iran’s 2009 election when statues were disappearing all over Tehran. The protagonist is a woman who begins searching for these missing statues, a search that takes her in places she could never have imagined.

Missaghi began the event with three longer readings from different parts of her novel. Her accent paired with the gorgeous language of her novel made listening to her enchanting. Her writing in some of the sections used repetition to reveal the full weight of the difficult narrative she was attempting to tell.

The next part of the book talk was a conversation between her and Sheida Dayani. Dayani is a theatre historian of Iran and preceptor in Persian at Harvard University’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations. She first asked Missaghi about her idea of putting the statues disappearing in conversation with disappearing bodies. Missaghi responded that it is natural to put the loss of human bodies and statues together with the loss of civil society that was happening.

One of the hardest parts, Missaghi commented, is that disappearance does not allow space for mourning. This loss is what Missaghi attempted to retell in the form of art, giving space for the mourning and remembrance that continues to exist.

Missaghi said that “Trans(re)lating House One” began as a separate class assignment about the “hermeneutics of [her] life at that moment.” She realized how much she missed Tehran, inspiring the beginnings of “Trans(re)lating House One.” It is a novel of her translating her experience and the Iranian experience while also relating these stories to her own and to one another.

After 2009, Missaghi became fascinated with her dreams and wanted to learn more about what they might mean, so she began keeping a dream journal. Although, she had no intention of using these dream journals as part of her novel, she had compiled over 100 pages of material just from her dreams. Once she decided she did want to include them in the novel, she asked an artist to create images out of the words of her dreams which are included in the novel.

Part of the title, “House One,” also came from her dreams. “House” and “one” were the most used words in her dream journals and, once she realized that, it felt perfect. Most of her dreams happened in her first childhood home in Tehran and including “House One” in the title felt like the right way to incorporate it into the vision of the book.

She also includes factual reports of people who were killed in different instances during the chaos of 2009. These reports of the dead, as Missaghi called them, were written after extensive research on her part, watching videos and reading about specific instances of violence. These are met with quotations from various historical figures that she believes help illuminate the reports and questions she struggles with throughout the book.

She delicately pieced together each of these parts, the reports, quotes, dreams, fiction elements and her own author commentary, to create “Trans(re)lating House One.” Everything about the novel is deliberately done. Some questions that came up for Missaghi when she was writing the novel included what it means for her to tell the story of the dead and what it means for her to be writing it in English.

She was going to wait to have conversations about these questions after the book was published, but she then decided that they should also be included within the book itself. Missaghi feels that her book connects history and literature with important questions that all artists have. She also commented on how her book is a combination of contradictions and readers must be comfortable living in a space where everything is in contradiction, and be able to see through it.

Missaghi said that one of the best examples of her readers making her see her own novel in a new way occurred at a reading when one of the attendees commented that she first started reading the book from page one, but stopped at some point and decided to do it differently. Instead of reading chronologically, this reader decided to open the book up to a random page and read from there, before closing it again and choosing another page. Missaghi never thought that someone would have that relationship with her book and saw the story she created as having its own life.

This story exemplifies all that Missaghi was doing through her novel and this talk. She is creating art out of tragedy, history, dreams and narrative plotlines in order to create a space for experiencing and conversing about all of these questions she constantly has. “Trans(re)lating House One” is an art piece that is truly Missaghi’s own and gives the reader space to perhaps come up with their own individual perspectives.

Brookline Booksmith hosts Poupeh Missaghi, author of 'Trans(re)lating House One'

A photo of Poupeh Missaghi's book "Trans(re)lating House One" is pictured on Feb. 12.