This review contains spoilers.

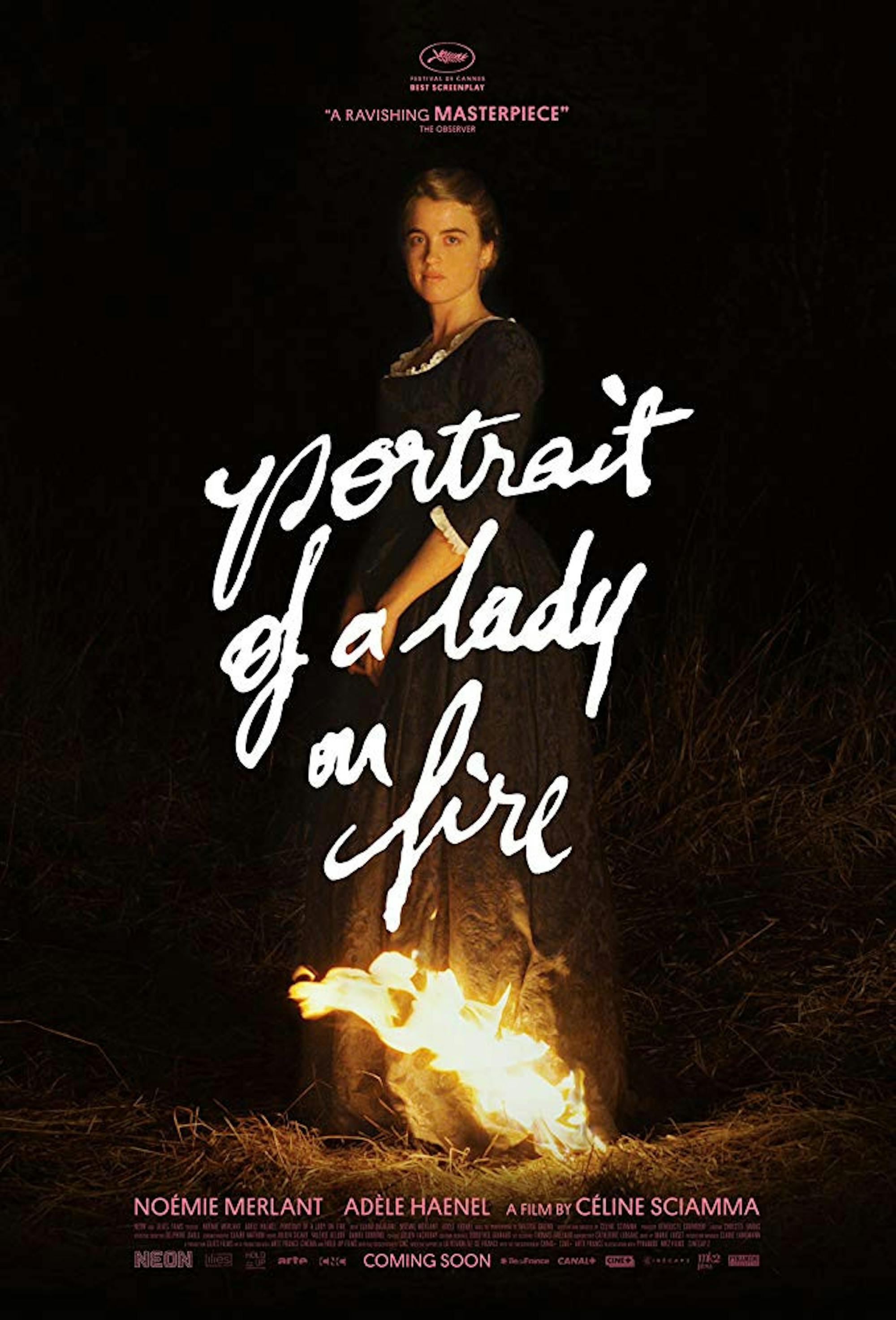

Shown by the Independent Film Festival Boston during its fifth annualFall Focusat The Brattle Theatre, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (2019) is a meticulous film. Following Marianne (Noémie Merlant), a painter, as she is hired to paint a portrait of Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), a woman being married to her dead sister’s betrothed, the film builds a late 18th century love story that crackles and aches with desire and loneliness. “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” takes its time with Marianne and Héloïse’s relationship while making it crystal clear that there is no good outcome or world where the two can be together. But before its last scene, a powerful release of heartache and love and longing, the film allows the viewer the chance to sit with Marianne and Héloïse.

“Portrait of a Lady on Fire” is both an intimate love story and social commentary. It spends much of its time presenting the struggles of its characters, from Héloïse’s engagement to a man she’s never met and servant Sophie’s (Luàna Bajrami) struggles with pregnancy and eventual abortion — a moment that’s particularly sobering as Sophie stares into the eyes of a baby as the procedure happens — to Marianne’s inability to advance her career. These threads focus the film on the internal and external struggles of the characters and allow the viewer to get attached to them. DirectorCéline Sciamma’s excellent work focuses the gaze on how Marianne and Héloïse intricately study one another as Héloïse’s future approaches.

For much of “Portrait of a Lady on Fire,”Marianne and Héloïse get too close and then quickly regain composure. They notice the small things. Marianne studies Héloïse without telling her that she’s painting the portrait for Héloïse’s future husband, pretending to be a companion on her daily walks and becoming fascinated with details, like her hands and how to paint her face when Héloïse doesn’t smile. The time they spend together is time of comfort and closeness. But there’s a volatile bubbling underneath the surface of Héloïse. In one particular scene, as she runs during one of the pair’s daily walks towards a cliff, Marianne is visibly horrified at the thought that Héloïse will end her life just as her sister did by jumping off the cliffs in order to escape the bleak future of marriage.

The film features beautiful shots of Marianne painting, with the camera watching closely as she takes her time to get Héloïse right. The effort is astounding — it's a reminder that any form of art, like painting or film or even love, is about observing the subject and understanding their essence. The scenes where Marianne and Héloïse walk along the cliffs on the coast are breathtaking; the water is rough and deep blue, and so is the attraction between the pair. If the cinematography of "Portrait of a Lady on Fire" is best described by anything, it's textured.

Some of the best moments of the film are shared between Marianne, Héloïse and Sophie. The three are seen playing cards and eating dinner together. Héloïse reads the story of Eurydice and Orpheus, and the three women debate Orpheus’ reasoning behind turning around and sealing Eurydice’s fate. This story proves important: Later in “Portrait of a Lady on Fire,” as Marianne rushes to leave the house after saying goodbye to Héloïse, Héloïse asks her to “turn around” and see her one last time. It seals Héloïse’s fate too, as she wears her white wedding gown that her mother brought to her. The wedding gown haunts Marianne throughout “Portrait of a Lady on Fire,” but it’s when Marianne is forced to leave Héloïse that the image becomes particularly harrowing.

But the pleasure between the two is secretive and wonderful. When they talk about individual quirks they have — things they do with their eyebrows or lips when they’re feeling stressed or nervous — the love is palpable. It’s these smiles that make the tears when the two aren’t together even more upsetting. This duality in “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” is shown best when Héloïse asks Marianne to draw herself on page 28 of a book. Later, after the two have gone their separate ways, Marianne sees a portrait in a gallery of Héloïse and her child — Héloïse is holding a book too, and the top of page 28 is shown. The impression is that Héloïse has been thinking about and looking at Marianne every day since their departure. It’s both the pleasure and pain of “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” — a reminder of the two being soulmates but unable to share their lives with one another.

And this is where “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” subjects its viewer to a painful burn. It never cuts corners. It delivers every moment in layers — sure, there’s happiness, but there’s pain and longing, too. It makes the viewer feel everything. There’s never any rest. And in the previously mentioned last scene, where Héloïse sits and watches an orchestra perform a song that Marianne once tried to play for her, the emotions that the film has been playing with all come to a head. Marianne watches Héloïse cry exasperatedly, smiling and shaking as the music pounds. Héloïse's reaction is the physical manifestation of everything that "Portrait of a Lady on Fire" realizes. It's impossible not to leave the theater reacting the same way.

'Portrait of a Lady on Fire' is slow-burning excellence

A promotional poster for 'Portrait of a Lady on Fire' (2019) is pictured.

Summary

Director Céline Sciamma takes her time making "Portrait of a Lady on Fire" into a work of art, an experience that is both heartbreaking and lovely.

5 Stars