Contemporary art arguably lives in a renewed era of “iconoclasm.” Twenty-first century artists still live in the legacy of the postmodernist disdain forArt Nouveau and veneration of the conceptual and the critical. Images are deemed inherently inessential as mere representations of reality, and artists are expected to think more solemnly beyond the visuals. The curators of the new exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) — “Kay Nielsen’s Enchanted Vision,” have moved beyond this ultra-realistic and pessimistic historical worldview to bring back the ethereal, the imaginative and the decorative. This Nielsen exhibition is the first one of its scale outside the artist’s home country, Denmark, in over 60 years. The MFA obtained the artworks on-view courtesy of American art collectors Kendra and Allan Daniel.

Kay Nielsen (1886–1957) was a Danish artist primarily known for his incredibly intricate book illustrations. A curious student of fantasy, Nielsen illustrated fairy tales of various origins, such as stories of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen as well as old Irish myths. Raised by a director father and actress mother, Nielsen developed an interest in the theatrical arts. He contributed to the production of Disney films such as “Fantasia” (1940) and “The Little Mermaid” (1980), and created stage and costume designs for various theatre works such as Shakespeare’s “The Tempest.”

Nielsen’s drawings claim heritage to an impressively eclectic list of artistic traditions. Nielsen’s command of lines with extensive and dramatic curvatures owes credit to the 20th-century British artist Aubrey Beardsley. Specifically, the complex drapery that dominates the field of “Yearning” from “The Book of Death” series (1910) by Nielsen recalls the cape of Salome in Beardsley’s illustration “The Peacock Skirt” (1894). However, though contributing to a similar compositional structure for “Yearning” as Beardsley's smooth strokes in “The Peacock Skirt,” Nielsen’s drapery differs from Beardsley’s in texture and connotation. The former is softer and more intricate, which recalls the incredibly delicate sculptures of Giovanni Strazza, a 19th-century Italian sculptor known for his portrayal of veiled women, specifically the Virgin Mary. The facial features of Strazza’s women-figures emerge subtly and naturally from “underneath” silky layers of a face veil, which drapes softly from the top of their heads. That being said,“Yearning” only partially replicates the sentimentality and naturalism of Strazza’s works, such as “The Veiled Virgin” (ca. 1850s), while retaining to some level the assertiveness of Beardsley’s works.

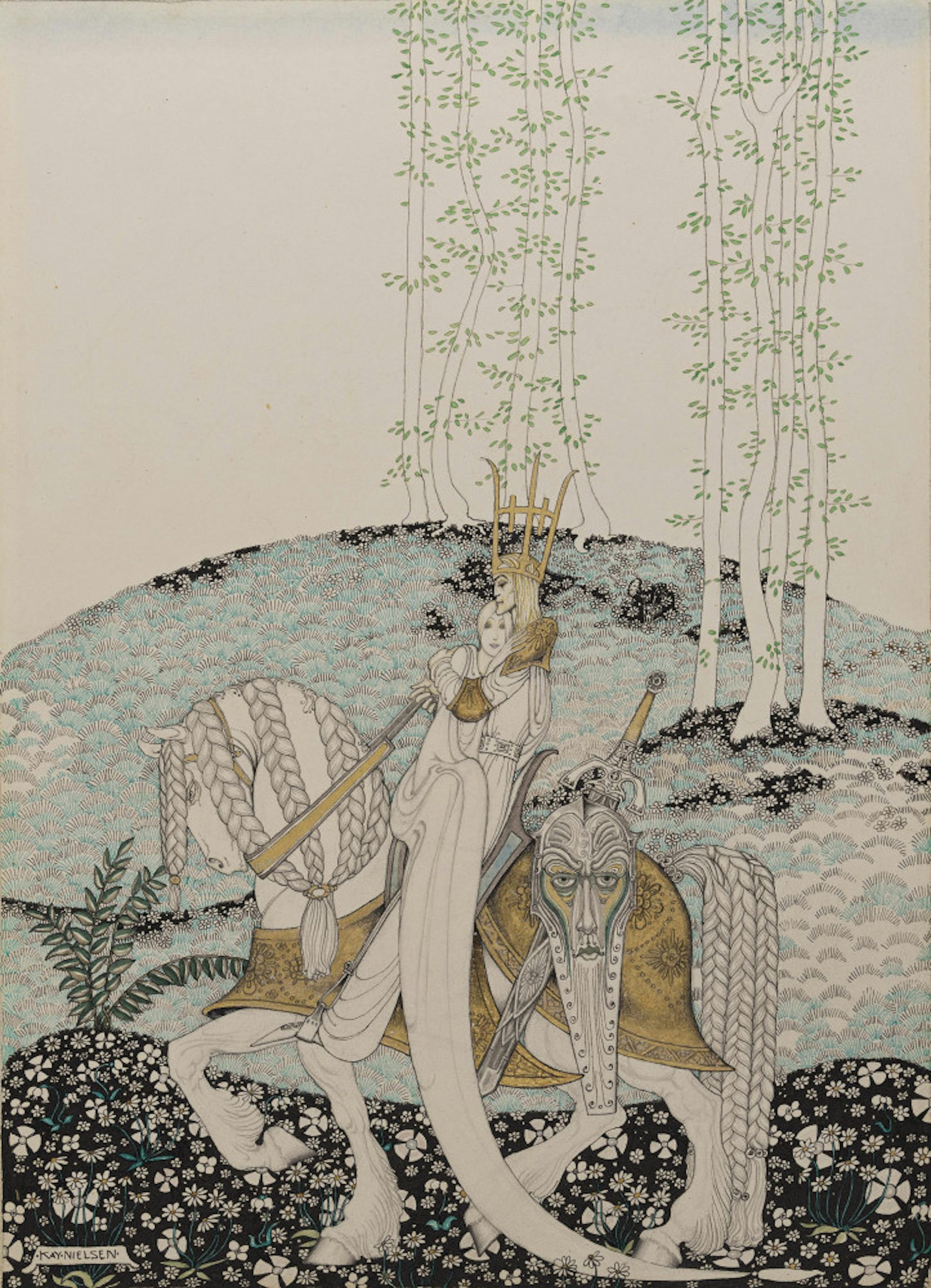

Nielsen’s works inherit older European traditions as well. In “Our Lady of Sorrows,” (1920), Nielsen revives the Byzantines’ love of the Christian subject, the Virgin Mary, and their obsession with golden paint. Nielsen also has a distinct predilection for elongated bodies, of not only humans, but also furniture and architecture. Such styles draw respectively from the 16th-century European mannerism and the 12th and 13th-century Gothic period. Apparent allusions to Medieval Irish illuminated manuscripts pervade Nielsen’s drawings. With the incredibly elaborate armor patterns in “So the man gave him a pair of snow-shoes” (1914) and the beautiful floral motifs in “Flower and Flames” (1921), Nielsen virtually re-interprets “The Book of Kells,”associating beauty with the spiritual and meditation.

Nielsen’s portrayal of landscape reflects Asian influences too. The cliff-like rock in Nielsen’s “You’ll come to three Princesses, whom you will see standing in the earth up to their necks, with only their heads out” (1914) cites precedent in scholar’s rocks in traditional Chinese gardens. The high level of stylization and control manifested in its representation, and again, the use of fine lines, pay homage to Japanese woodblock prints. The reference to Japanese art becomes more explicit in “And flitted away as far as they could from the Castle that lay East of the Sun and West of the Moon” (1913). At the bottom of this Nielsen drawing is a thin layer of blue ocean water, which seems to have almost literally flowed from “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” (ca. 1829–1833), with its tri-color palette of sky blue, navy blue, and white.

Learning from styles of various geographical, temporal and religious origins, Nielsen’s works, perhaps paradoxically, constitute a unique identity of its own. His drawings are at once familiar and alien, culturally derivative and autonomous. The dualistic nature of Nielsen’s artworks almost evokes a sense of “visual magical realism,” encouraging their viewers to inquire into the wonderland beneath the mundane world.

The exhibition will stay on view until Jan. 20, 2020. All Tufts students may be granted free admission upon presenting valid Tufts IDs at the reception desk.

Enchanted: The elegant otherworlds of Kay Nielsen born from masters of the past

Illustration from East of the Sun and West of the Moon, Old Tales from the North (published 1914), 1913–1914 Transparent watercolor, pen and brush and ink, gesso and metallic paint over graphite.