For the last couple of months, the “Ansel Adams: In Our Time” exhibit has been the buzz of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), but there is a second, smaller but arguably more impressive and impactful, photography exhibit at the MFA right now. It is Graciela Iturbide’s "Mexico:" an intimate and stunning collection of Graciela Iturbide’s photography from the 1970s to the present. From nursing plants to slaughtering goats, this exhibit brings aspects of Mexican culture and personal fascinations together in a collection that is sometimes joyful, sometimes devastating but always alive.

The exhibit is split into nine sections with themes including birds, death, “fiestas” and specific studies of Mexican women. Three focus on indigenous communities, the Zapotec, Mixtec and Seri, and another, in a different gallery, captured Frida Kahlo’s bathroom that had been sealed off for over 50 years. Iturbide’s photographs of people are often close-up and personal; all the portraits have an air of dignity about them, and her candid pictures also capture people, often women, in the midst of something personal. But Iturbide also has a fascination with birds — she can depict them in the same manner as Alfred Hitchcock — as well as plants. Her photographs of the Oaxaca Ethnobotanical Gardens show cacti and trees “in intensive care," as the MFA describes, supported by rope rigs and with IV-like bags hanging off their branches. Are people hurting them or healing them?

These themes of death, sacrifice and tradition in Mexico show up all over Iturbide’s work; one of the sections of the exhibit is simply titled “Death.” Some photographs are almost too painful to look at, capturing the intense grief that comes with death, and others are celebratory. Mexico celebrates the Day of the Dead (“Día de Muertos”), a holiday to pray and remember loved ones who have passed. But it is a day of honor more than grief, and Iturbide captures the dynamism of the celebrations, even if the black and white hides the colors of the flowers and skulls (none of the photographs are in color). Despite being a universal concept, death specifically speaks to Mexico’s history. In “Mexico… I want to get to know you!” (1975), the titular phrase is the slogan of the Mexican tourism bureau and hangs in a sign above a store. Inside the store is a skull with a swastika-emblazoned helmet, and a shadowy figure in the window. Here, Iturbide questions what Mexico advertises, what it offers and how it reconciles itself in a modern world catered to the West.

The Day of the Dead is a pre-colonial celebration that has continued in modern times, and Iturbide takes care to also capture others that are not so famous outside of Mexico. One example is her series on “muxes,” a Juchitec practice of men dressing as women and, according to the exhibit, “a Zapotec gender status reported to have existed for centuries.” Some, of a muxe named Magnolia, are poised and girlish. Another, titled “Muxe" (1979), shows a muxe turning with comical, laissez-faire sexuality holding a cigarette. Iturbide is wonderful at capturing both historic pride and individual personalities in her work.

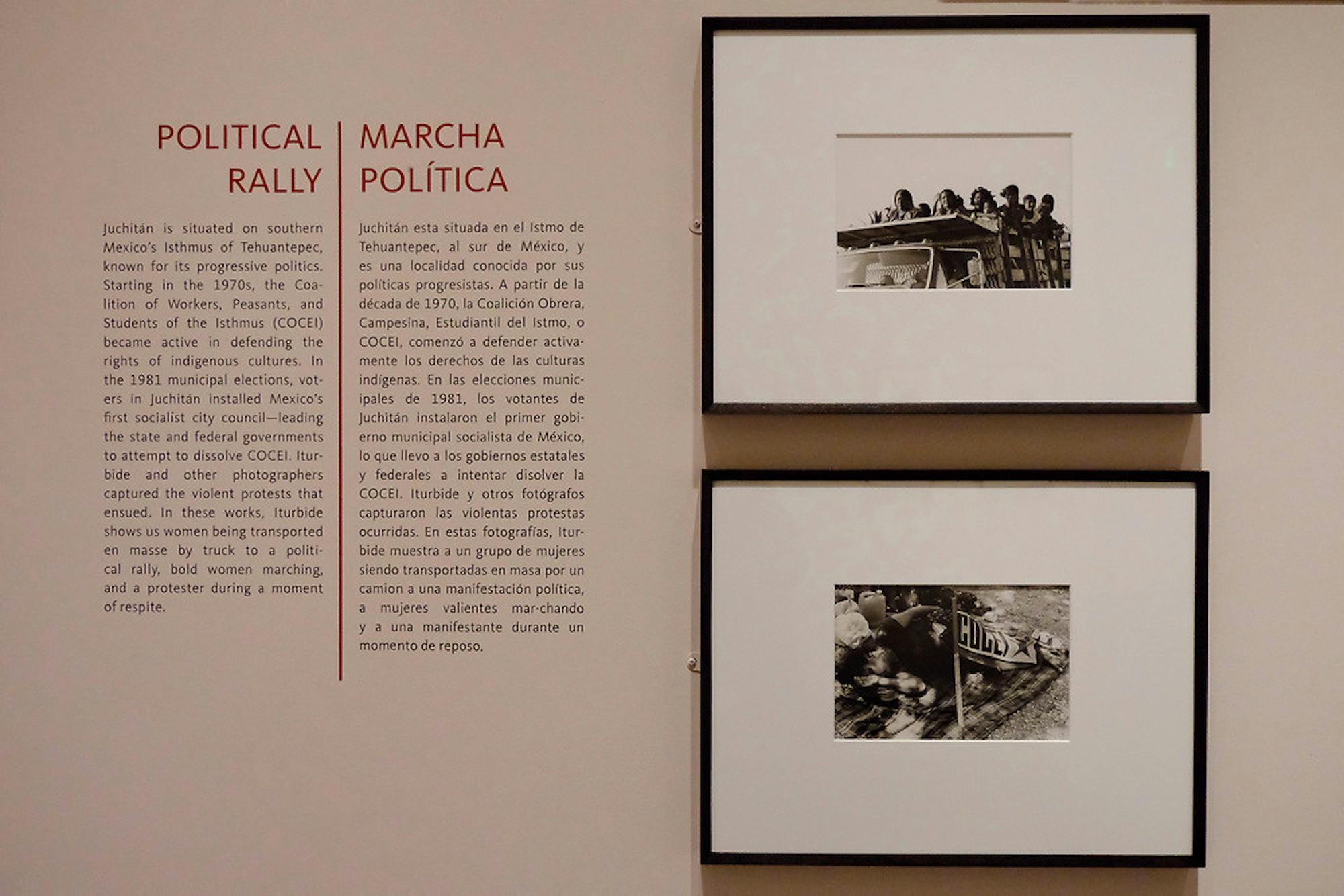

Where Iturbide is truly exceptional is in her ability to capture personhood. Her pictures often frame people in distinct compositions, as with her famous piece of a Seri woman from behind, wearing a traditional dress, holding a boombox and seemingly running into the stunning landscape ahead of her (“Angel Woman,” 1979). Iturbide is not afraid of showing women slaughtering goats, protesting in political rallies and doing work while men lie drunk in the background. Even in her photographs of Kahlo’s bathroom, which include no people (except for her own feet in the bath, as a lovely tribute to Kahlo’s “What the Water Gave Me”), she captures Frida’s individuality in her belongings. Objects that represented her poor health and suffering, like enemas and prescribed narcotics, were left in front of those representing strength and perseverance, like a portrait of Stalin. Kahlo’s and Iturbide’s idiosyncrasies come through in this particular collection, and it is an exceptionally personal end to a personal, as well as cultural, exhibit.

Overall, Graciela Iturbide’s "Mexico” is one of the best photography exhibits the MFA has had in years, showing a dynamism that flows throughout Mexico and all its crevices. It is unfortunate that it is shown concurrently with Ansel Adams’ exhibit, because this one is far more personal and yet grander than any landscape; it is the story of people and a place, deeply connected.

Graciela Iturbide's 'Mexico' offers a touching, intimate look at Mexico and its people

Summary

'Graciela Iturbide's Mexico' at the MFA is a collection of the famed Mexican photographer's works from the last several decades which explodes with life and poignancy

5 Stars