The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s current exhibition, “Armenia!,” is the first major exhibition of Armenian art in the United States. An exhibition at the New York institution is no small feat and surely legitimizes the art it portrays by launching it into the art history canon. Looking at the rare and beautiful objects on display, it is hard to understand why Armenian art has not featured more prominently in art history's texts and scholarship.

The exhibition, open until Jan. 13, brings together several types of objects such as manuscripts, sculpture, textiles and even church architectural models, showcasing the unique style of Armenian art while highlighting the talent of Armenian craftspeople. The exhibition is held in its own special space, tucked between the Greek and Roman art and European sculpture halls of the Met. And while some may take issue with the exhibition’s positioning, one can also see it as a way of inserting art that has been overlooked into the same space as art that has been revered for centuries. The exhibition's location prompts visitors to ponder: How is one more artistically valuable than the other, and why do we see it that way?

“Armenia!” also takes into account the various influences of other cultures in Armenian art, as Armenians were often intermediaries between different cultures due to their location in Asia Minor. What is so interesting about Armenian art — and one can see this through the various objects on exhibition — is how it can take on different influences but still remain utterly unique. The exhibition is a 'palette' refresher to the cynical art historian and art lover, as it is a departure from many of the special exhibitions one may expect to see at the Met. It is also a departure from the Met’s permanent collection as well — the museum is separated into wings based on geography and time (Asian, American, modern, etc.), which leaves artworks that fall in between these categories completely out of the picture.

Another important takeaway from the show is how it challenges notions of what is and is not considered important art. It provides visitors with the perfect starting point to go back to their art history textbooks and ask what is missing. Art history has a tendency to get rid of people’s national identities and heritages in order to produce a streamlined understanding of art and its context, but in the process, one loses the richness of the history of a work and the person who created it. For a few examples from outside the world of Armenian art, the author of the "Dada Manifesto," Tristan Tzara, was a Romanian-Jewish artist; the great surrealist Man Ray’s birth name was Emmanuel Radnitzky, born to Russian-Jewish immigrants; and the list could go on. Particular fervor has also been put into promoting the history of women artists, who have also been omitted and sorely overlooked or tokenized by art historians. Contemporary art activist groups such as the Guerrilla Girls attempt to challenge the severe underrepresentation of women artists in major art institutions.

Exhibitions like “Armenia!” show how institutions can feature art histories that have not previously been given proper thought and rigor. The show is successful in how it displays its objects with respect and does not treat the subject as insular. Viewers leave the exhibition resoundingly sure that Armenian art deserves even more attention and scholarship than the art world currently provides. They too may be inspired to learn more about Armenian art or look into who has been erased from art history — and more importantly, to find out why.

Metropolitan Museum of Art's 'Armenia!' takes hard look at representation in art history

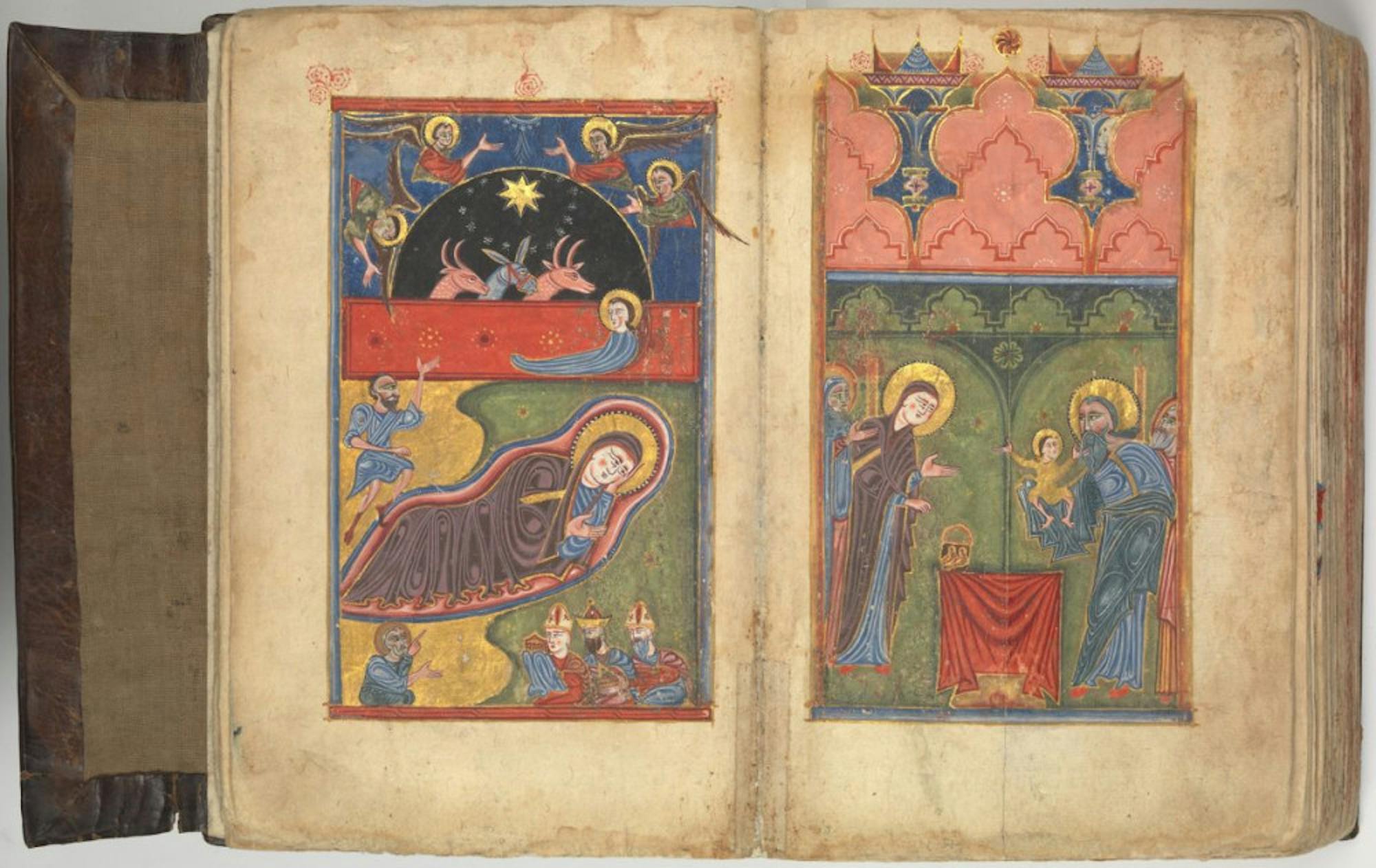

'The Nativity / Presentation in the Temple,' folios 5v-6r of manuscript object 'Four Gospels in Armenian' featured in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's 'Armenia!' exhibition, is pictured.