In May 1968, a nationwide general strike led by students and factory workers crippled the French economy and plunged the nation into a state of chaos. The situation reached a boiling point by May 29 when, fearing another revolution, President Charles De Gaulle fled the country to Germany, leaving the country without a leader for a few hours. To this day, the May 1968 crisis, despite having few lasting political effects, remains a watershed moment in French society and culture. Though the crisis caught many inside and outside France completely off-guard, one needs only to look at films like “Belle de Jour” (1967) to capture the seething turmoil of a nation and society on the brink.

Undergoing a re-release in the United States to celebrate the 50th anniversary of its American premiere, “Belle de Jour” is directed by surrealist icon Luis Buñuel. It follows the wealthy young housewife Séverine Serizy (Catherine Deneuve) as she finds herself unable to feel any physical desire for her dutiful but bland doctor husband, Pierre (Jean Sorel), instead having lurid sexual fantasies of humilation, bondage and sadomasochism. Whether these fantasies are linked to past sexual abuse intimated in a few stream-of-consciousness flashbacks is left to the audience to decide.

Upon a salacious encounter with Monsieur Husson (Michel Piccoli), a family friend whom Séverine finds herself simultaneously intrigued and repulsed by, she becomes a high-class prostitute at the brothel of Madame Anaïs (Geneviève Page) in the afternoons while Pierre is at work. There, she takes the name “Belle de Jour” (beauty of the day), a play on a French euphemism for a prostitute, “belle de nuit” (beauty of the night). However, when a young gangster client (Pierre Clémenti) becomes increasingly volatile and repeatedly pries Séverine for information about her personal life, she begins to fear for the safety of Pierre and herself.

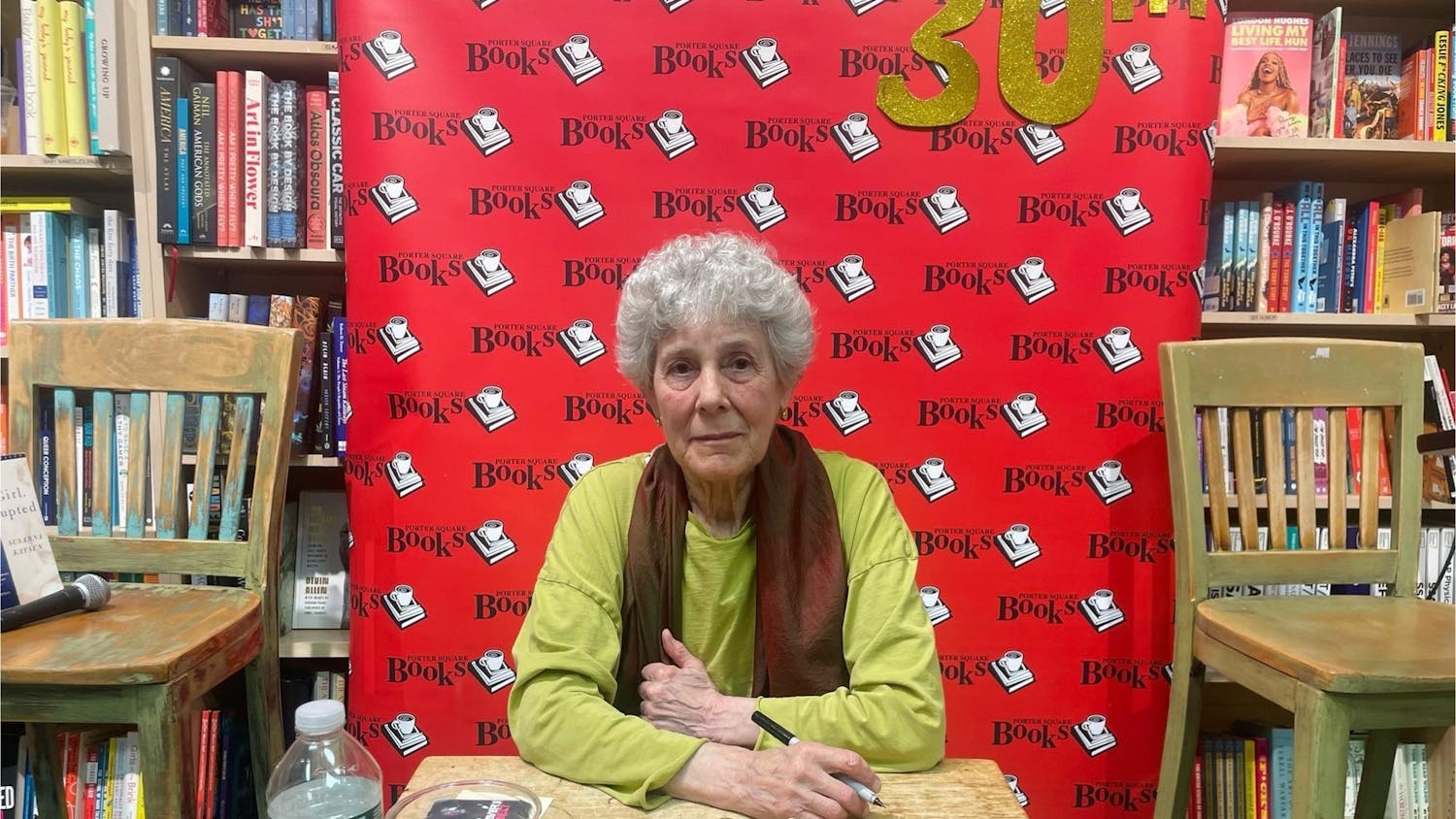

Catherine Deneuve’s turn as Séverine in “Belle de Jour” remains arguably her most iconic role, and, watching the film, it is clear to see why. Each of Deneuve’s deliveries conveys a perfect blend of eagerness, ingenue-style naivety and disgust at her own carnal desire. With simply a look down, a furrow of her brow or a shifty, withdrawn walk, she communicates a diverse array of emotions and fears. Séverine, above all, is a woman who has taken her dissatisfaction with humdrum everyday life and channeled it into an exciting, forbidden and dangerous world. Deneuve flawlessly portrays her most important characteristic; she is engulfed in her desire and simply cannot stop.

Buñuel’s direction and signature visual style expertly portray Séverine’s opposed yet intimately connected worlds. With gorgeous set design, impeccably, effortlessly stylish costumes (many of them designed by Yves St. Laurent) and shifting camerawork, Buñuel is able to create a film that oozes a classic jet-age coolness and sophistication. Yet, with every zoom on Séverine’s face as she faces her high-paying, high-flying clients, we are reminded that the dual worlds the film occupies will soon come crashing together, with unpredictable results. Soon, her life as Belle de Jour will have to reckon with her life as Séverine.

The twofold existence permeating the film is wholly symptomatic of the larger turmoil gripping French society in the mid-1960s. Though her home life is one of spacious Paris apartments, country club tennis and weekend ski resort outings, Séverine retains a powerful sense of disenchantment and forbidden desire bubbling below the surface of her psyche. Like Séverine, France was fed up with that world and ready to unleash its previously cast-aside strains of thought and groups of people. That is the most telling effect of “Belle de Jour:” Its story captures a whole society just before a radical transformation.

'Belle de Jour' is a sultry portrait of its time

Catherine Deneuve in 'Belle de Jour' (1967).