From the opening of “The Divine Order,” the rollicking German-language Swiss drama from writer and director Petra Volpe, the family is painted as manufactured. Theresa (Rachel Braunschweig) asks her sister Nora (Marie Leuenberger) to talk some sense into Theresa’s daughter, Hanna (Ella Rumpf). Theresa frames her daughter’s behavior by the gaze, remarking on her daughter’s new nickname: "The Village Bike." From the outset, the women are painted as consumable. Nora, while attempting unsuccessfully to convert her niece, mentions that the behavior she’s exhibiting, namely spending a lot of time with different men, will keep her from finding a husband. Hanna, acting as a stand-in for the radicalizing feminist politics of her time in 1970s Switzerland, rejects that notion and declares that she isn’t at all interested in marriage. The gendered dynamics between Nora and Hanna, in conjunction with their love for each other, makes palpable the film’s criticisms of gender roles and expectations. “The Divine Order” expounds upon these dynamics with potent effect — it won awards at both the Tribeca Film Festival and the Traverse City Film Festival.

In a later scene, as Nora and her family sit around the dinner table, her father-in-law (Peter Freiburghaus) performs his nominal duty: he dominates, controls and steers the conversation this way and that, silencing and shaming his sons and his daughters-in-law alike. The camera stages the dinner table well as a set piece. The table itself reinforces the feminist overtones of "The Divine Order"; the family sits with the men at or closest to the head, and an oppressive silence seems to surround the women during the conversation. This scene ends with a powerful shot from behind the father-in-law’s head. The shot is disorienting, as a deft destruction of the fourth wall — the shot from behind his head forces us to acknowledge our own viewership, and to the intimate battlefield that director Petra Volpe has sculpted out of the dining room. As the smoke clears, we are placed behind him, and, contrary to his potent control of the dining room, he is vulnerable. The shot frames his head, and therefore his knowledge, by the condescending gaze of the family around him.

The movie succeeds because Petra Volpe uses the camera as an auxiliary character through which she examines the world. The camera itself is an assertion of agency, and as Volpe controls the fate of the film with her camera, the women in “The Divine Order” wrest the control of their own fate with their vote. The struggle at the center of “The Divine Order," isn’t just a powerful collective of women in a small town in Switzerland, going on strike, but a meaningful challenge to the status quo and a wonderful exposition of the power in agency.

Marriage looms like a specter throughout the film. The defining moment of the first half of the film occurs when Nora tells her husband Hans (Maximilian Simonischek) that she wants to seek a job as a secretary. The air of the room is stale — this isn’t the first time she’s brought it up. Hans suggests that Nora should only work if the family finds it necessary, citing his friends’ wives who have jobs. Here, Hans performs masculinity much like his father, and their resemblance is uncanny. Hans coldly ends the conversation by exclaiming that it is legal for him to deny her the right to work. This moment crystallizes the struggle for suffrage at its most intimate moment — patriarchy as ideology is distilled into a moment of denial and invalidation. This would turn out to be the final impetus that pushes Nora toward organizing for women’s suffrage.

That connection between gender performance, marriage and the vote deepens the film’s discussion of gender relations. Not only are women kept powerless in marriage, but the film forces us to examine closely the specifics of that powerlessness and its adherence to a gender performance.

'The Divine Order' is a familial power struggle writ large

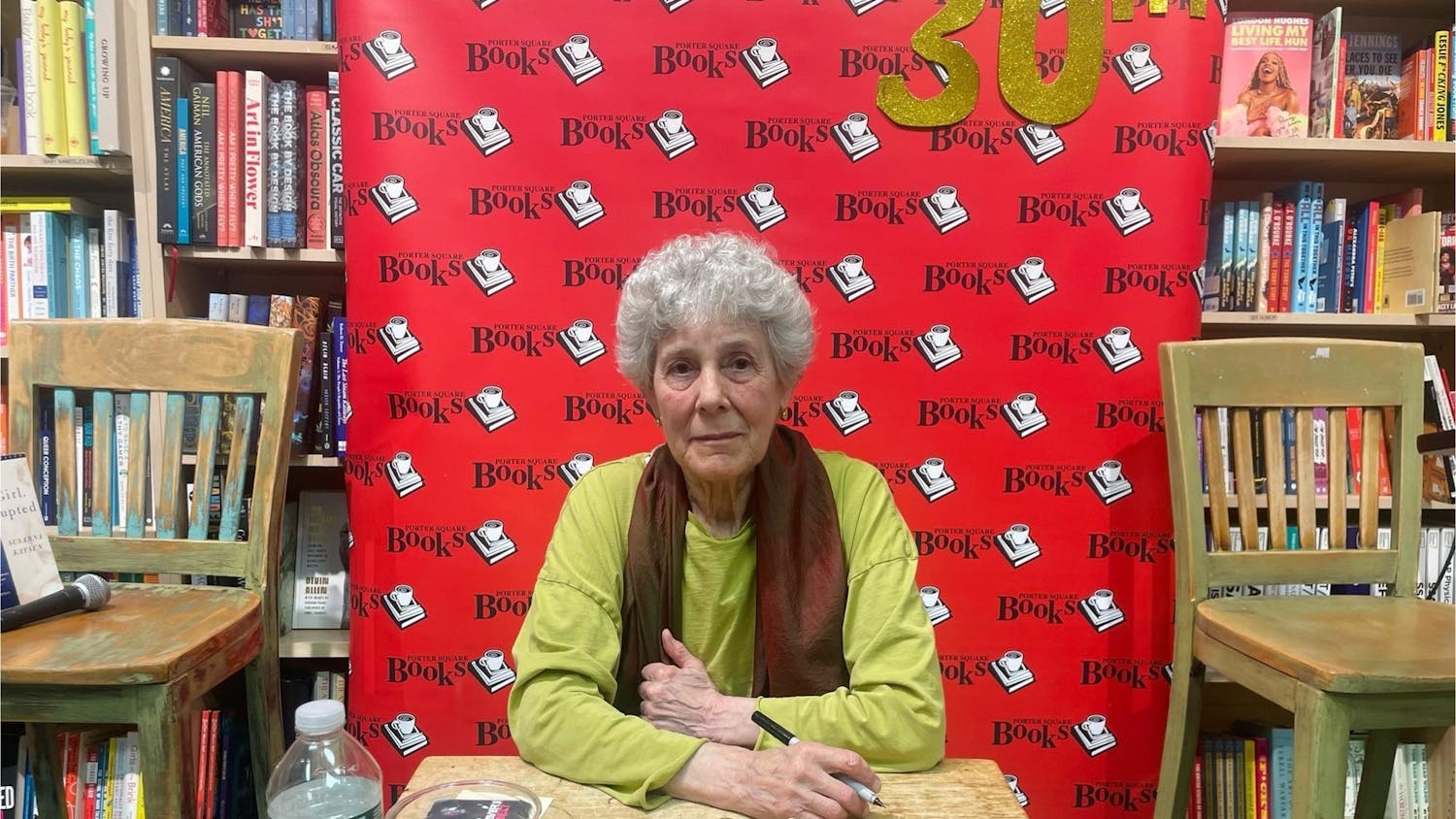

Marie Leuenberger from “The Divine Order", a 2017 movie about women's suffrage in 1971 in Switzerland, is pictured.

Summary

"The Divine Order" conjoins marriage as end goal, the performance of gender as a means of social control, and institutional backlash to deviation in order to connect the theoretical concept of a heteropatriarchal power structure with the lived experiences of women.

4 Stars