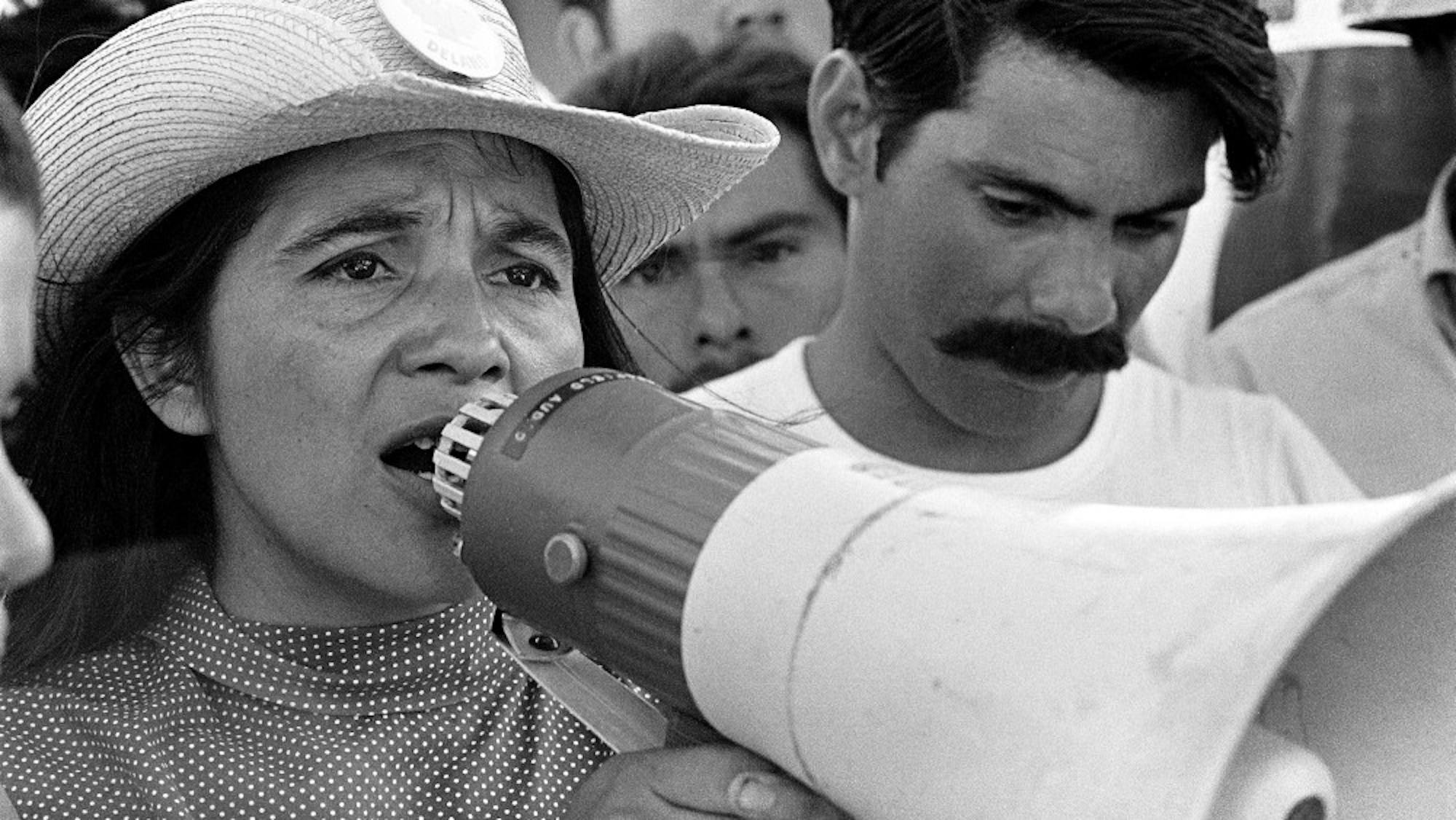

The subject of the upcoming documentary film “Dolores” (2017), 87-year-old labor-rights activist and legend Dolores Huerta, remains “the most vocal activist you’ve never heard of.” As cofounder of the United Farm Workers labor union with Cesar Chavez, Huerta spearheaded the Delano grape strike in 1965 and played a key role in negotiating fair contracts for migrant workers in the United States. A living legend in her own right, Huerta continues her advocacy with the Dolores Huerta Foundation.

Her story is one of a life dedicated to battling institutions of racism, sexism and classism. It is also one of the resilient power of individuals fighting collectively against incredible odds. Using powerful archival footage and thorough, challenging interviews, “Dolores” celebrates an exceptional life while also illuminating a chapter of U.S. history with grace and urgency.

The Daily had the opportunity to discuss the upcoming release of “Dolores” over the phone with the film’s director and a close friend of Huerta's, Peter Bratt. “Dolores” will have its wide release in theaters on Friday.

The Tufts Daily (TD): What brought you initially to this project?

Peter Bratt (PB): I came from a narrative film background and had never done a ... feature documentary. The process began about five years ago, when I got a call from Carlos Santana, the legendary musician, who said, “We have to make this film. Right now.” I told him I was not a documentary filmmaker, but that didn’t matter to him.

Ultimately, Dolores was the one who allowed this story to be told, because she had been approached a few other times in the past and never felt it was the right time. When Carlos put in the request, she said yes and we began this process.

TD: How do you even begin the process of distilling a larger-than-life woman and an entire movement into 90 minutes of film?

PB: My family has a connection to Dolores’ family; my mother knew her from the movement days in the '60s and '70s. My mother was also a single mother who was an activist. First, I had to remove my thinking of “Dolores, the icon.” As someone who was from that particular community, I had to approach it from a point of view of pure storytelling. If we were going to do this, I wanted to be able to talk about things that she would most likely be uncomfortable with. From my relationship with her kids, I knew that they had it somewhat tough. I wanted to get into that and really capture the spirit of who she is. I knew that we would just be skimming the surface of the work that she’s done over seven decades. She’s worked on almost every issue you can think of in the last 75 years.

TD: During the five years you spent making the film, what were the some things you learned about film and Dolores? Where did those lessons come from?

PB: In terms of filmmaking, I learned that whether you’re making a documentary or a feature narrative, at the end of the day you’re telling a story. A lot of this generation, they’re hearing about Dolores Huerta for the first time in their life. You can’t just jump in and start telling the story with all the intricacies about labor history in California, because you’re going to lose your audience. You have to figure out how to keep your audience engaged with the material. That way, you’re using the same skills as you would in a narrative film; you’re telling a story and you have to make it interesting [and] entertaining.

I also realized that with doc-filmmaking, you’re almost walking on a tightwire. You count on discovering a great deal of the narrative and the themes in the process of discovery in your research. You’re hoping to discover the themes you’re going to build the narrative around in the process. And sometimes it takes a long time to emerge, as they did in this film.

In terms of Dolores, what I took away from this process is that she is the consumate and relentless organizer. She does not stop. When you have your subject for 12 or 16 hours a day, usually the subject lets her hair down, so to speak. But with Dolores, what you see is what you get. Even when the camera lights come off, she’s always focused on the job of organizing, of furthering her cause. That blew me away, to realize that there’s somebody who moves and acts at that level, all the time ... She wore out my crew. Even now, during the tour of the film, I had to go home and take a week off between all the promotion. She’s been going nonstop. And she’s 87. Her children joke that she’s an alien from another planet.

TD: Along those lines, to what extent would you connect your work with Dolores’? To what extent do you feel that your job as a filmmaker and artist is activism?

PB: If you’re an independent filmmaker, you’re used to the long haul. Developing a project, it takes years to raise money ... And then when you’re finished, you’re not guaranteed distribution. So sometimes that may require you to go around with a project for a long period of time. So just by being an indie filmmaker you’re already prepared to be engaged in something that’s going to take a very long time. But after seeing the commitment of people like Dolores and Cesar Chavez, including those who gave their lives, and are still in the game after decades, and sometimes fighting for a cause that they know they won’t live to see achieved, that’s a really sobering thing. So as a filmmaker, it takes a long time, but it’s nothing compared to the trek of someone like Dolores Huerta.

TD: Do you see yourself as an 87-year-old someday making films and telling stories?

PB: Hopefully when I’m 87, I’ll have that much commitment and passion for what I’m doing, truly. I would die a happy man if I could make it that far and have that much vigor, enthusiasm and excitement. You don’t meet people like Dolores everyday. The sheer commitment, it’s overwhelming.

TD: From observing her for so long, what do you think is the key to her longevity?

PB: She believes in what she’s doing, she really believes that people have power. For her organizing is like a magic wand, a kind of a superpower. You go into a community that feels powerless, and you help organize and develop leadership within that community, and then you see those people come together, organize and create change in their lives. Dolores also lives in the communities that she works in. She has the camaraderie, love, support and respect of those that she struggles with. That also keeps her virile [and] alive.

TD: Do you feel filmmaking is your “magic wand?”

PB: Filmmaking is great, but it doesn’t replace being in the community and being civically engaged. I also work in the nonprofit world. It’s a different kind of field, but you’re still working with people and collaborating to make change in your community that sometimes doesn’t achieve equity. So it affects me, my people, my family, my community. But in terms of filmmaking, it’s a craft, an art form. You can marry the two [filmmaking and activism], but it has to be done using those tools. I don’t think you can just go out there. It has to be woven; it can’t be over the head.

TD: What advice might you give to a young person right now who is inspired by the work of Dolores Huerta and your own work as a filmmaker, or people who watch your film?

PB: There’s an opportunity right now in the current political climate. We need all hands on deck. I’m a believer now in what Dolores said, that the power is in each individual. Everyone has that power. The movement worked with the most powerless class, undocumented non-English speaking farm workers. That community got empowered, and it created change. I believe in that. We need engagement right now.

I advise people to find out what it is you want to work for. Go volunteer. Get involved. You can vote, you can campaign, you can run. And marching helps put pressure, but you have to vote, you have to get civically engaged. I hear people from filmmaking say, "There’s filmmaking and there’s activism, and you don’t mix them." But I believe you can do it all.

Editor's Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q&A: 'Dolores' director Peter Bratt talks storytelling, community activism

United Farm Workers leader, Dolores Huerta, organizes marchers on 2nd day of March Coachella in 1969.