Making a biopic about J.D. Salinger, one of the most private and enigmatic literary figures in history, is a risky undertaking. From his time in World War II to his lifelong problems with women and his later years in seclusion, Salinger hid what made him tick up until his death in 2010. Director Danny Strong, who wrote the screenplays for “The Butler” (2013) and parts one and two of “Mockingjay" (2014-2015), is not afraid to speculate in "Rebel in the Rye," an interpretive Salinger biopic released Sept. 8. The result is a warm, if not entirely convincing, love letter to the “rebel” of American literature.

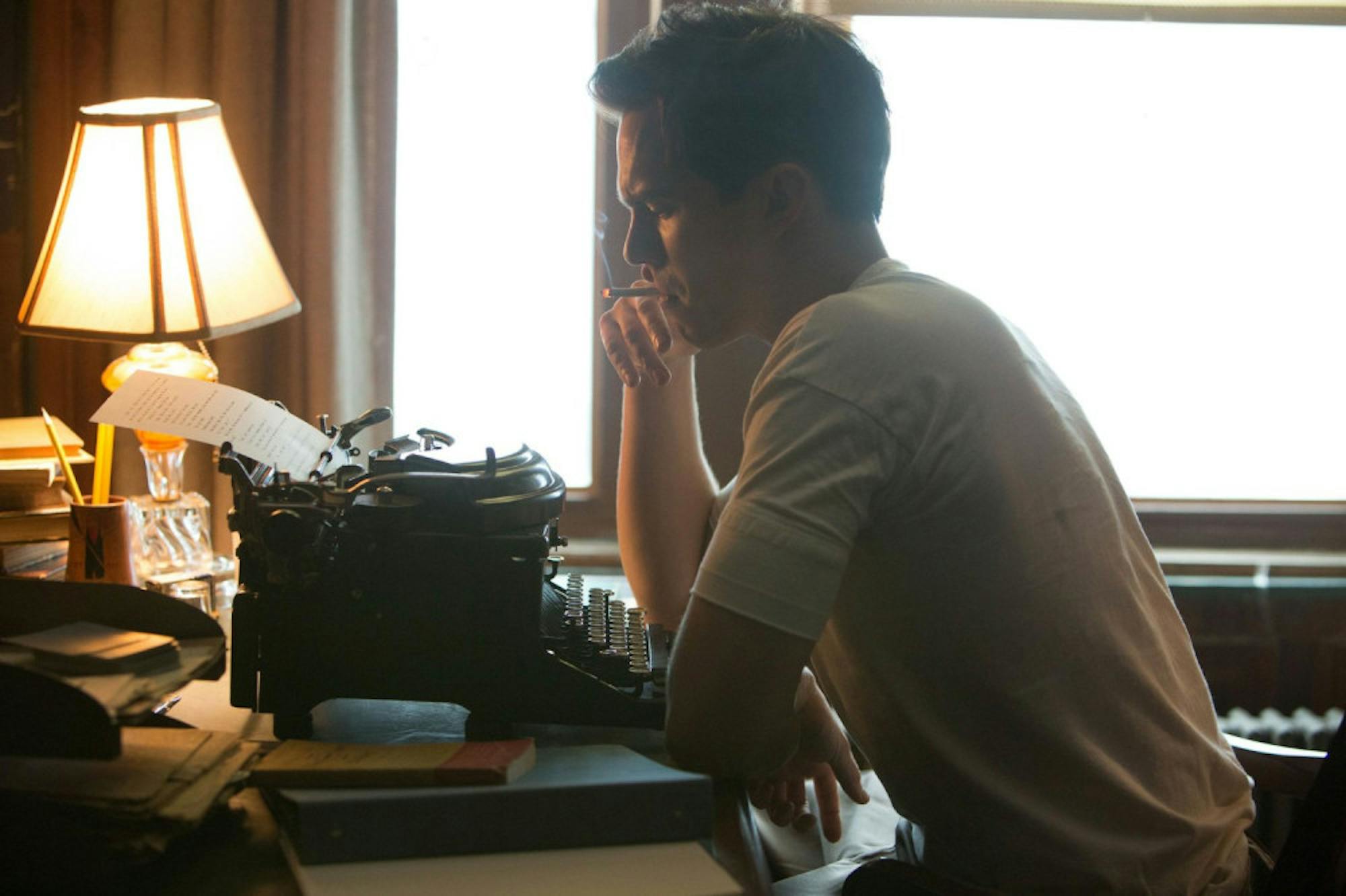

Strong’s Salinger, played by the little-too-handsome Nicholas Hoult, projects more and more instability as his fame and talent grow. In his early days of “The Young Folks” (1940), Salinger is still wet behind the ears, frenzied and flourishing under the mentorship of his professor and first publisher, Whit Burnett, who is played by Kevin Spacey in easily the best performance of the movie.

Salinger dates Oona O’Neill, the daughter of Eugene O’Neill, before she unceremoniously dumps him for Charlie Chaplin. He begins submitting his stories to The New Yorker and, despite rejection, refuses to make his work more commercial. After his service in World War II, in which he stormed Normandy on D-Day and liberated a concentration camp, he is hospitalized for emotional trauma and begins showing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. He breezes through his first wife in eight months, takes up meditation and watches his publishing success grow until reaching cult status with the release of “The Catcher in the Rye" (1951). And yet, the timeline is no more a path to success than it is a descent into suspicion, fury and reclusion.

Despite the drama of the story, Strong’s depiction falls flat. Salinger’s flashbacks to the war are kitschy and unconvincing, and his estrangement from Burnett and his first wife are never explored. There are some interesting, tense moments between Salinger and his unsupportive father, but those are not expanded to their full potential. Perhaps due to Strong’s obvious love for Salinger, the movie also glosses over Salinger’s questionable history with women; he was married three times, had numerous affairs and entered a relationship with an 18-year-old first-year at Yale when he was 53.

But perhaps the biggest flaw of the movie is Strong’s consistent portrayal of Salinger as a real-life Holden Caulfield. Salinger himself stated in a 1953 interview that Holden’s childhood was similar to his own, and he refused to sell the movie rights to “Catcher” because he considered the novel untranslatable into film, and because no one (other than himself) could possibly play Holden. But Strong's connections are exaggerated. Salinger’s narration throughout the movie includes a few too many famous quotes from “Catcher," relying on the assumption that audiences will recognize them, and even shows Salinger experiencing a moment of clarity as he watches a carousel in a park like in the famous scene from “Catcher."

In the movie, Salinger describes Holden as his companion during the war and as a voice for all of his frustrations. This may be so, but the character of Holden doesn’t hold as much depth as half the members of the Glass family, who are featured in several of Salinger’s short stories and each provide a piece of Salinger's own psyche. The movie likes to explore Salinger's frustrations and trauma, but it never shows his real genius. As he watches a moment of everyday life unfold before him, the camera goes into slow motion and then pans to him writing his next inspired masterpiece in a frenzy. This kind of writing process doesn’t give enough credit to Salinger or to his work. According to the movie, the author is a watchful recipient of opportunity unfolding in front of him, only capturing the essence of his own brilliance and philosophy when he writes “Catcher." It is a frustrating implication for those Salinger fans, such as this writer, who considers “Franny and Zooey” (1961) a far superior and more subtle novel.

The are occasional moments where Salinger’s connection to Holden is a success. In one scene, an editor suggests that Salinger’s first depiction of Holden Caulfield in “Slight Rebellion Off Madison” (1946) should make Holden’s alcoholism more obvious. Salinger is stunned, and responds defensively: “He’s not an alcoholic.” Although it is never mentioned again, almost every scene before and after this one shows Salinger with a drink in his hand or an arm’s length away. There isn’t much evidence, however, that Salinger had an alcohol dependency in real life, or that the times when he and his professor drank together in bars were so entertaining, or that they even happened at all.

The movie ultimately portrays Salinger as its director wants to see him. Such an attempt is, if you’ll excuse the terminology, a little phony.

'Rebel in the Rye' is flattering, but falls flat

J.D. Salinger (Nicholas Hoult) sits in front of his type writer in the biographical drama film "Rebel in the Rye" (2017).

Summary

'Rebel in the Rye' is a love letter to J.D. Salinger, but not a very well written one, emphasizing narrative consistency over subtlety and nuance.

2 Stars