“His messages became… curt,” a friend explained to me over coffee, shrugging her shoulders. She was describing a shift that had taken place in an undefined relationship: the trailing-off in text messages that often signals the end of knowing the person.

“Mmm,” I agreed. “You always know.” I didn’t mean her, specifically. I meant that most people can feel when the shift has taken place: It's a knowledge that settles into you.

Later that night, the same friend texted me a screenshot of a conversation that Curt Guy had initiated. Everything was back to normal. Somehow, in the course of a few hours, two thoughts had been true: You always know, and you never know.

Aside from the fact that texting is an ambiguous form of communication, there is the ambiguity of human beings to contend with. Our words and gestures offer only a glimpse of who we are and what we want, while other things circle inside of us, unseen.

In her poem “Summer,” the contemporary poet Robin Coste Lewis writes about finding a snake skin on her porch two mornings in a row:

"I pretended as if I did not see them, nor understand what I knew to be circling inside me. Instead, every hour I told my son to stop with his incessant back-chat. I peeled a banana. And cursed God — His arrogance, His gall — to still expect our devotion after creating love. And mosquitoes. I showed my son the papery dead skins so he could know, too, what it feels like when something shows up at your door — twice — telling you what you already know.”

Many of the poems in Lewis’ collection, “Voyage of the Sable Venus” (2015), are pages long and stunningly complex. They mimic linguistic patterns and draw from her knowledge of Sanskrit. The title poem is composed solely of titles of artwork depicting black women from ancient to modern times.

In comparison, “Summer” seems straightforward. The speaker tells a story in easy statements and with humor. But the poem derives its power from what is inaccessible to the reader: what the speaker “kn[ows] to be circling inside [her].”

Lewis doesn’t exploit the shedding of skin as a metaphor for change. She seems more interested in the idea of what was once part of the body and no longer is: “the papery dead skins,” the banana peel, the child chatting in the background. What the speaker and the snake both know, then, is a kind of loss.

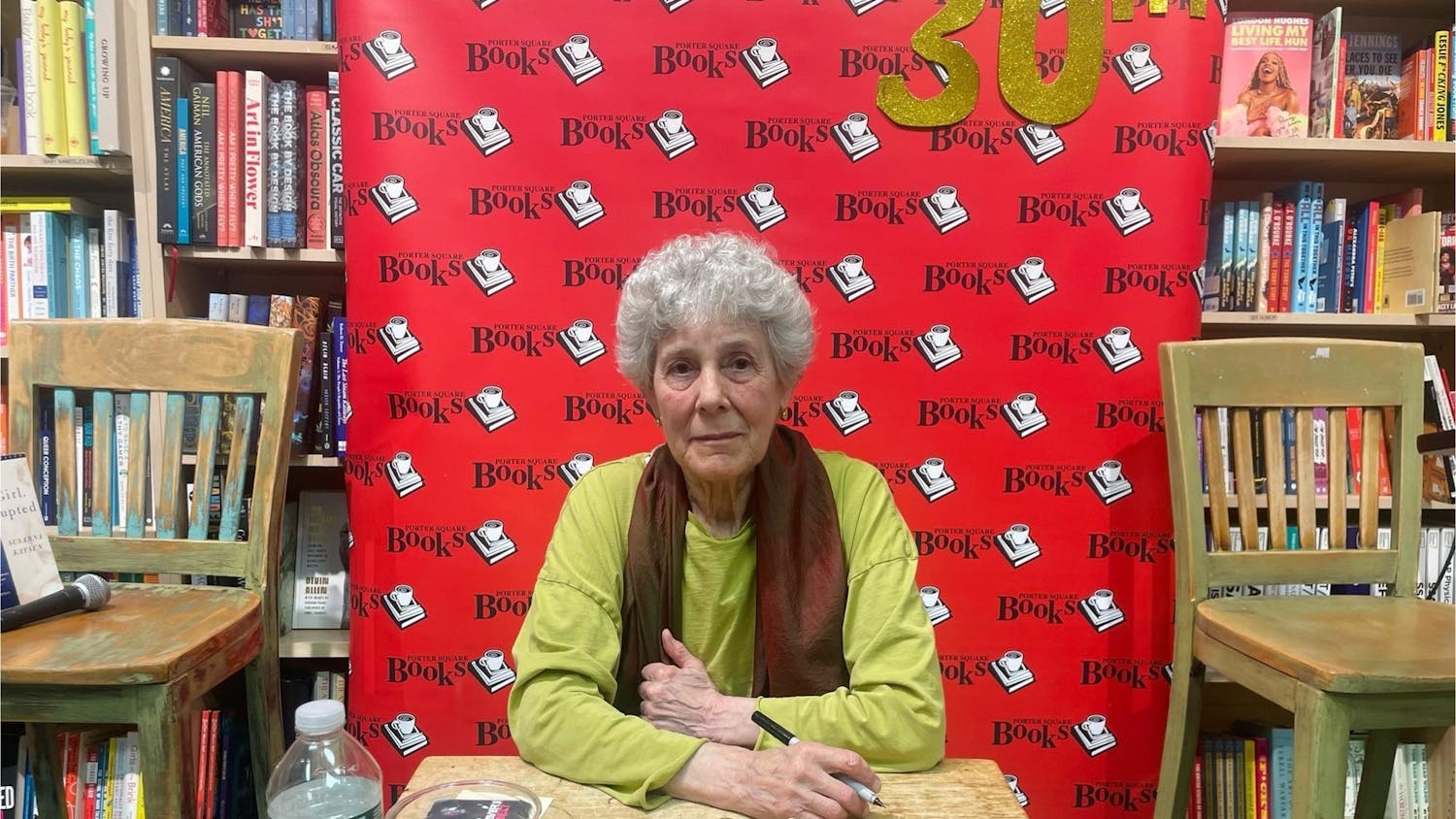

When I heard Lewis read the poem aloud at an event last month on the Tufts campus, the last six words struck me as urgent and sad: “telling you what you already know.” She spoke them slowly and intently. They followed me out into the dark when the reading was over. I didn’t know exactly what they meant. What I wanted to carry with me was their ambiguity, which — like the ambiguity of curt text messages — could mean anything at all.