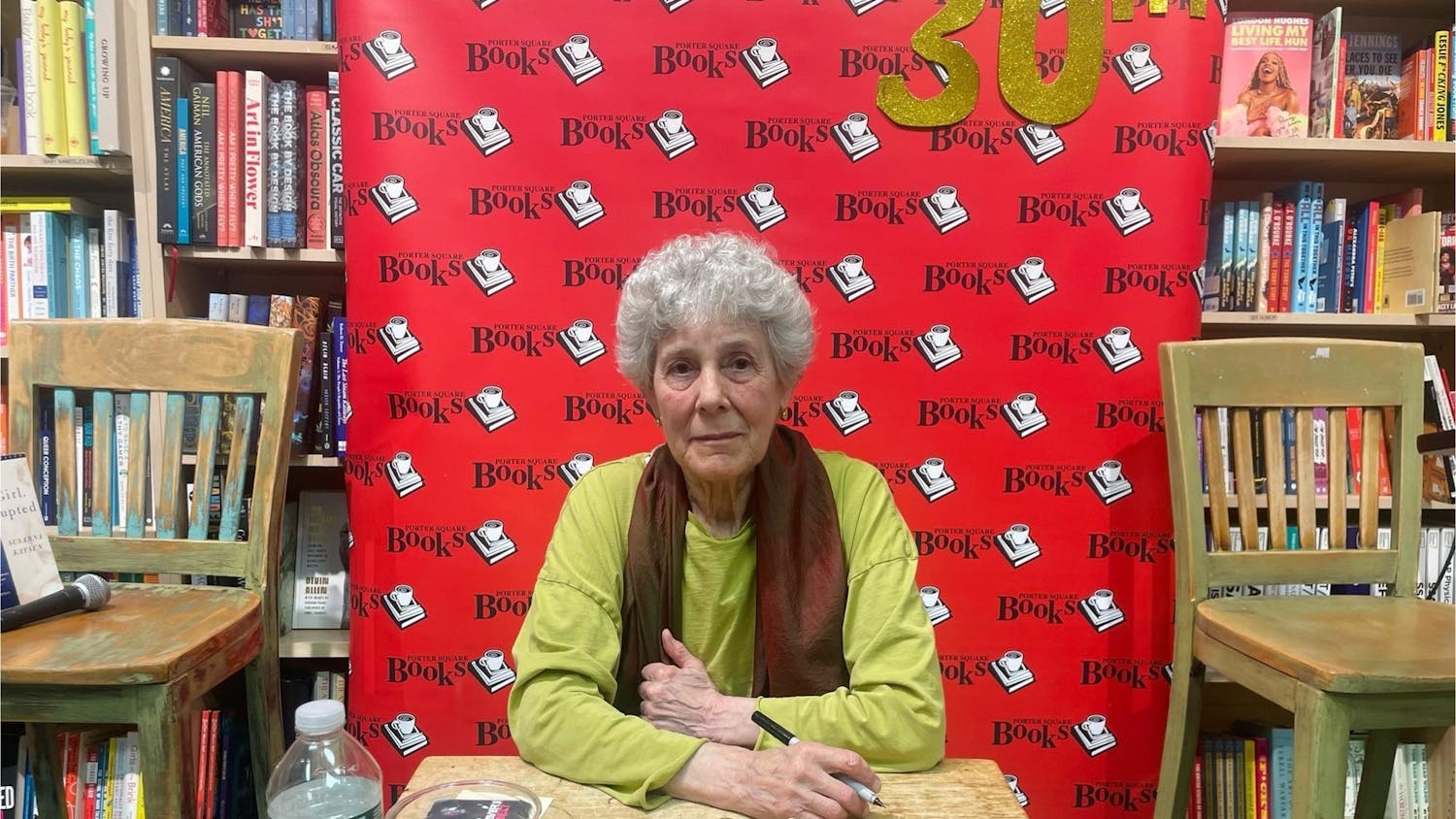

Poets Rachel McKibbens and Dominique Christina, who make up spoken word duo Mother Tongue, performed at Tufts on Friday at an event hosted by the Spoken Word Alliance At Tufts (SWAT). Hailed for their talent, bluntness and social activism, McKibbens and Christina delved into a myriad of themes including identity, family life, past trauma and political and racial dissidence in America.

Although currently touring as the unit Mother Tongue, McKibbens and Christina are acclaimed poets in their own right. McKibbens is the author of "Pink Elephant" (2009) and "Into the Dark and Emptying Field" (2013), while Christina is the author of "The Bones, The Breaking, The Balm: A Colored Girl’s Hymnal" (2014), "They Are All Me" (2015) and "This Is Woman’s Work" (2015). Both poets also hold championship titles at the Women of the World Poetry Slam. As artists, McKibbens and Christina complement each other well: Their poems find common ground in their commentaries on violence, repression and life as women of color (Christina is African-American and McKibbens is Mexican).

In her opening piece, McKibbens said she came from her mother with “arms, legs and fists.” She came to the stage in a similar fashion. Much of her poetry is personal, recalling her childhood with an abusive father and an absent, schizophrenic mother. The resonance, brilliance and violence of McKibbens' poetry is striking. It is clear to listeners that she writes poetry for herself rather than an audience. In her performance of “Bruja’s Soliloquy,” she recalls her childhood belief that manhood was freedom: “I kissed the girls too hard, riddled my tongue with a father’s profanity because I thought that this was how to become a boy.” But later in the poem she asks, “What greater burden, what more unconquerable revolt is there than that of a resurrected woman?”

She also honored her niece, who passed away before the age of two, in “Salve,” a poem that recognizes her grief but pushes unrelentingly for a lesson within it. She stared at the audience and asked, “How alive are you right now? ... What haven’t you done? What are you doing? ... The child is buried in the ground, her bones are winning, but your flesh is still yours.” Other poems of the night touched on attempts to run away from home, a white women posting her tattoo of a Mayan god on Facebook ("O, to be white in America, to wake up knowing every god is your god"), and “the time my father bashed my face in.” The brief moments of humor in some of her poems are startling but don’t feel out of place. Listeners understand that the life in her poems is in her perspective, with laughter in one line and fury the next.

Christina’s poetry is similarly powerful, forcing her listeners to acknowledge history past and present. In her poem “Summer of Violence,” referencing the rise in gang violence in her hometown of Denver, Colo. in the summer of 1993, she describes burying friends, seeing young boys buy their own caskets in advance and recognizing the horror and grief that never went away. She asserts, “Your tomorrow has a bullet in it, ask Trayvon Martin. Your tomorrow has a bullet in it, ask Jordan Davis." She gave a tribute to both Whitney Houston and her late neighbor Cojo, a Vietnam veteran haunted by the war and considering suicide but “only knew how to kill the innocent.” None of American history is left unscathed.

A Huffington Post writer contacted Christina, asking, “If 2017 was a poem, what would it be called?” The answer was an entire poem: It “can’t be called anything with life inside of it … 2017 is no poem. It’s a pipeline trying to breach an ocean.” Her words were a foretelling but also an appeal: “If there is any prayer left in this world, let it be what remains in our hearts.” In perhaps her best performance of the night, “Karma,” Christina gave a passionate account of her identity and purpose as a black woman facing a history of oppression, saying, “We become poets in an attempt to tether words to righteousness.” It is clear her righteousness is one written "in fire,” not pacifism. She spoke, “Tell 'Massa he can call me Karma, I am refreshing the bones of a witch … tell 'Massa I’m coming back.”

Both Christina and McKibbens agreed the pain they have experienced in their lives is very evident in their poetry, but their poetry is also a survival mechanism in response to that pain. They connect because of their ability to overcome their experiences and, in Christina’s words, “refusing to die.” Their lives are not about the future or the luxury of dreams but about living and thriving in the beautiful present.

Jukurious Davis, a junior on SWAT's executive board, praised the poets for being “so incredibly blunt and honest and raw."

"We as students and members of higher education are conditioned to express things in a prim and proper and polite way,” he said, noting that in contrast, Mother Tongue was honest and had "real conversations that need to be had."

The poets echoed this need for honesty. When asked by an audience member why they write, Christina shrugged and responded, “Because I’ll die if I don’t;" McKibbens shrugged and responded, “Because it’s illegal to stab people."

Spoken word group Mother Tongue offers truth without apologies