There is no question why Kerry James Marshall’s retrospective exhibit at the Met Breuer in New York City is entitled "Mastry." Containing 72 paintings from his 35-year career, the show displays how Marshall’s vision conjures itself over time from each work. Initially an abstract painter, Marshall dedicated the rest of his career to figural painting after reading Ralph Ellison’s "Invisible Man" (1952). Marshall's work taps into the invisibility and the chosen visibility of black people across media and art. It depicts the real implications of police brutality, the history of violence against black Americans, the stereotypes and trauma they face and how all of these factors shape the way that black people are depicted in art and the ways that they view themselves psychologically.

Marshall has the ability to command various mediums to articulate the limitations of and exclusionary depictions in Western art by using such art as a reference. In addition, he is able to bridge the gap between technical virtuosity and his message for visual justice, reminding viewers that art can be thoughtful, beautiful and, most of all, powerful. Through his work, Marshall explores the following question: How many masters in the art world are black? It is undeniable that Marshall has earned the title.

In his first figural work, "A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Formal Self"(1980), Marshall depicts himself using very black paint. The figure is almost the exact same shade of black as the background, making Marshall seem invisible. Depicting the figure’s skin as black also creates a very flat figure, reminiscent of medieval and early renaissance portraiture. This historical art reference is further implied by Marshall’s use of tempera, a medium utilized by medieval and early renaissance artists primarily for biblically-themed portraits.

This work itself ushers in Marshall’s own Renaissance and marks a critical turning point in the kind of work Marshall is creating, as well as the ideas behind it. The figure’s eyes and mouth are starch white, creating a strong contrast between the white and black parts of Marshall’s body. The cheeky grin as well as the unnatural shape of the eyes also hints at Western culture's historically racist depictions of black people, mimicking the aesthetics of blackface and minstrel shows.

Some of Marshall's figures are more naturalistic than others. It is clear that his differently-stylized depictions of black figures are not a reflection on his artistic capability, but rather a choice he makes depending on the specific context in which the figures reside. In his series on black love and domesticity, the figures are not too naturalistic as they aim to depict the frivolity of love between black people, a rare scene in the Western art world. In contrast, when Marshall paints black artists and intellectuals such as in "Untitled (Painter)" (1955), the figures are completely naturalistic and three-dimensional. Similarly, in his paintings of fictional black painters, Marshall draws figures as naturalistically as possible to fill in what he calls the “vacuum in the image bank” concerning the representation of black people.

The exhibition description states that “blackness is a medium” in Marshall’s paintings. However, the artist seems to suggest that the color black transcends the medium to become a form of light. Black is color itself, and it enhances and transforms other colors. It turns neon pink pale, transforms cobalt into blush blue and gives green an emerald hue.

The complexity in Marshall’s utilization of color theory mimics the complexity of being black in America. His work fills in the gaps that mainstream visual cultures don't always offer: He captures black people in their most tender moments of love for themselves, other people and the natural or historical world around them. They illustrate many traits that make us human - but are only visualized in our culture through the depiction of white bodies. Marshall’s paintings, while blissfully beautiful and artistically sublime, also highlight the failings of colorblindness in the art world and how there are variations of hue in black pigment too.

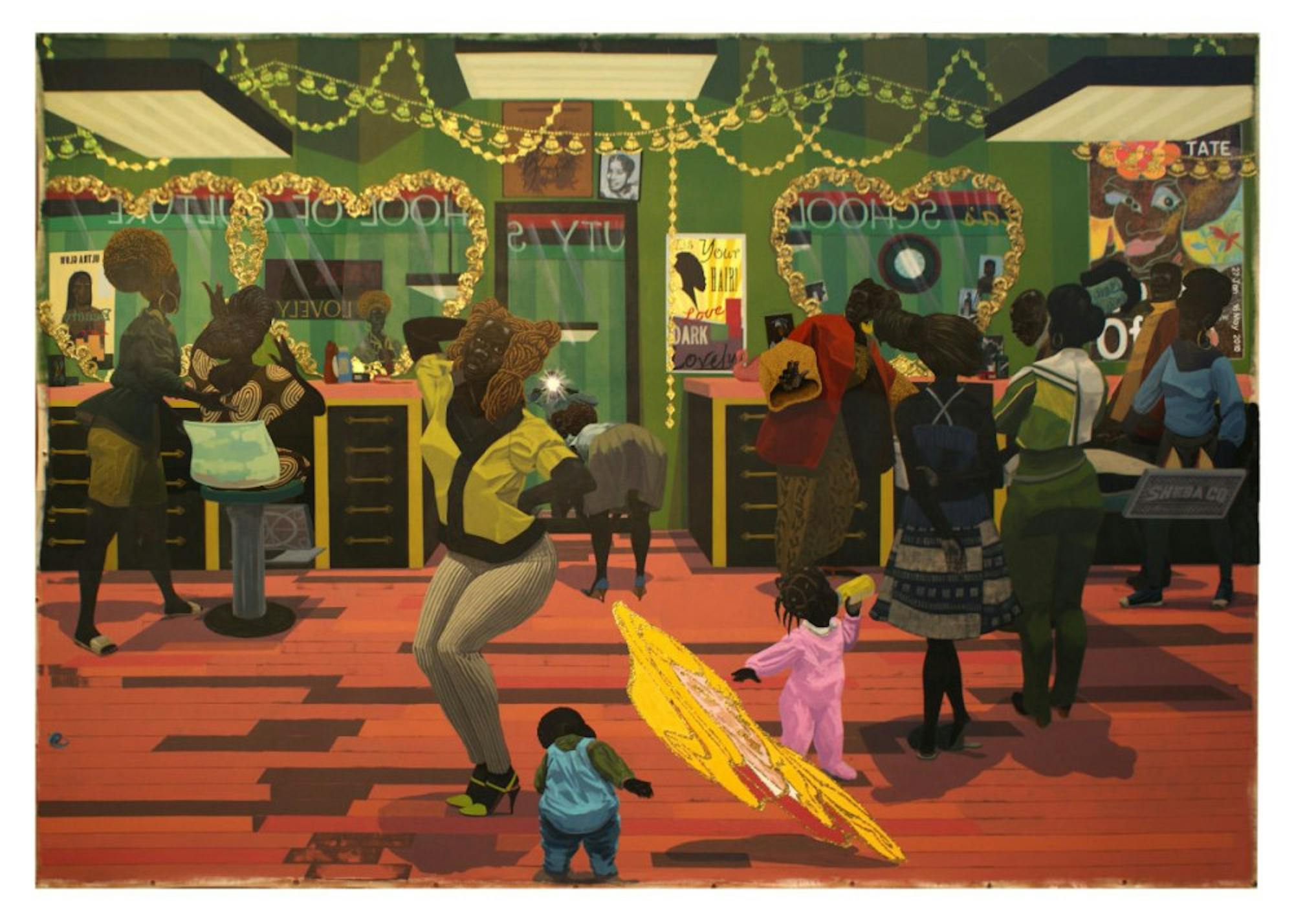

At the end of "Mastry," the viewer is left wondering, "How far have we come?" The answer to this question can be found in one of Marshall's more recent works, "School of Beauty, School of Culture" (2012). In the center of the image, a black woman proudly presents herself with her natural hair. Heart-shaped mirrors reveal a banner with the title of the work boasting the Pan-African colors, and the women in the salon wear African prints. The work is on loan from the Birmingham Museum of Art, where until age nine, Marshall could only attend the museum on “Negro Tuesdays.”

He never did. To have a work where black women proudly claim their own beauty and worth in a museum where black museumgoers could not freely attend is inspiring in its own right. But if viewers still have to be reminded of black people’s worth, of the normalcy of their lives and of their capability for success, therein lies the problem itself.

Kerry James Marshall's retrospective 'Mastry' explores black Americans' traumas, joys

Summary

"Mastry" validates Kerry James Marshall's status as one of the most talented contemporary artists today.

4.5 Stars