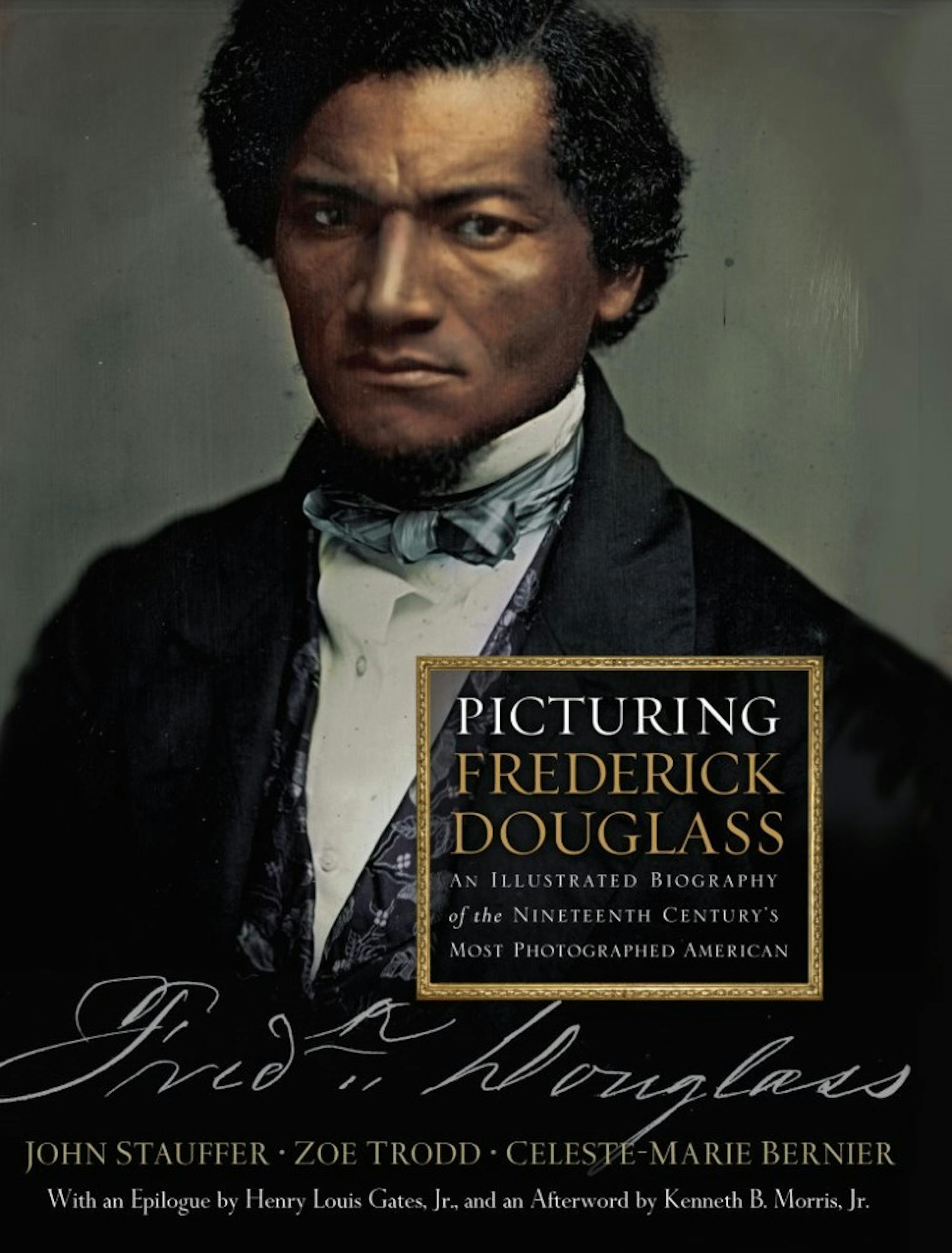

The Museum of African American History on Beacon Hill debuted its newest exhibit, “Picturing Frederick Douglass,” on July 15, 2015. Based on a book of the same name by John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd and Celeste-Marie Bernier, the exhibit showcases the many portraits of Frederick Douglass, the most photographed American of the 19th century.

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born a slave, circa 1818, on a plantation in Talbot County, Md. From his escape to the north in 1838 until his death in 1895, he lived under the surname Douglass and became an iconic abolitionist, orator and statesman as well as the author of several bestselling autobiographies.

He also loved photography since its inception around 1840; ;his first portrait was taken around 1841. Douglass built his life around self-transformation: from slave to freeman, to radical, to statesman. This growth was paralleled by the development of the country, including its division, reunification and emancipation of slavery. To Douglass, the development of photography was also key to personal and national transformation. It was a tool for social reform, as it forced its viewers to see the subject in a real and unflinching light and humanized the subjects themselves.

The exhibit is organized chronologically: from 1840 to 1860, the 1860s and the 1870s onward. Through the course of his life, the natures of the portraits change in subtle but various ways. Many of the most recognizable pictures of Douglass were pre-Civil War, featuring furrowed brows, direct stares into the camera and Douglass either cropped at the chest or displaying clenched fists. Often forgoing smiles, intricate backgrounds and any other objects, he sought to create an image of a dignified, serious citizen and leader. In particular, he was very conscious of dispelling the caricature of a happy, content or passive slave.

In Douglass' last autobiography, "The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass" (1881), he wrote, “I have written in part for the encouragement of a class whose aspirations need the stimulus of success.” It is clear he wanted to present himself in a similarly strong, confident way through his portraits.

During the Civil War period, Douglass became a respected radical Republican, not simply a fringe revolutionary, especially after Abraham Lincoln consulted him at the White House. In these pictures, Douglass experiments with different head and facial hairstyles, but he retains the same expression of "majestic wrath," as the exhibit staff call it.

The staff also calculated that before and during the war, almost half of the portraits showed Douglass staring into the camera; after the war, he only took that position 20 percent of the time. The exhibit also observed that Douglass no longer clenched his fists in pictures and began to favor a three-quarter turn pose, common for statesmen at the time, instead of his trademark forward-facing pose. By the 1870s, as president of the National Convention of Colored Citizens and later United States Marshal for Washington, D.C., he became more comfortable with conventional turned-torso positions as well as profile shots. But it was not until late October 1894, in the last picture taken of him before he died, that Douglass is clearly shown smiling.

Douglass was a man with a myriad of talents, passions and observations, and so any exhibit dedicated to his life and image is sure to be fascinating. But the museum did an exceptional job of pointing out trends, contexts and rarer pictures that a regular viewer might not otherwise appreciate. The props Douglass used were rare and significant; George Schreiber’s 1870 portrait shows Douglass holding the top of a cane, only just visible at the bottom of the picture. It was the cane of the late Lincoln, given to Douglass by Mary Todd Lincoln.

The exhibit includes rare pictures of Douglass with his grandson Joseph playing the violin in 1894, a passion he shared with Joseph that made Joseph a favorite grandchild. It includes a picture of Douglass in Washington, D.C., in 1893 -- not a portrait but a candid photograph of Douglass' back as he sits at his desk, writing, surrounded by papers, books and his violin. Most interestingly, it displays a picture of Lincoln’s second inaugural address, with Douglass, Lincoln and future assassin John Wilkes Booth all present. The exhibit also shows some of Douglass’ most famous and relevant quotes, a first edition of an 1883 Harper’s Weekly with Douglass on the cover and pictures of famous street art featuring Douglass, including one at King Open School in Cambridge titled “The Arc of History is Long."

This exhibit runs through July and the entry fee is a suggested donation. As a resident of New Bedford, Douglass is a fascinating part of Massachusetts history that this museum portrays masterfully.

'Picturing Frederick Douglass' is informative, thought-provoking

Summary

Masterfully curated, "Picturing Frederick Douglass" sheds a light one of the most influential figures of the abolitionist movement.

4 Stars