It is evident from “Hacksaw Ridge,” Mel Gibson’s first film as a director since “Apocalypto” (2006), that the director's filmmaking ability has not waned in the intervening decade.

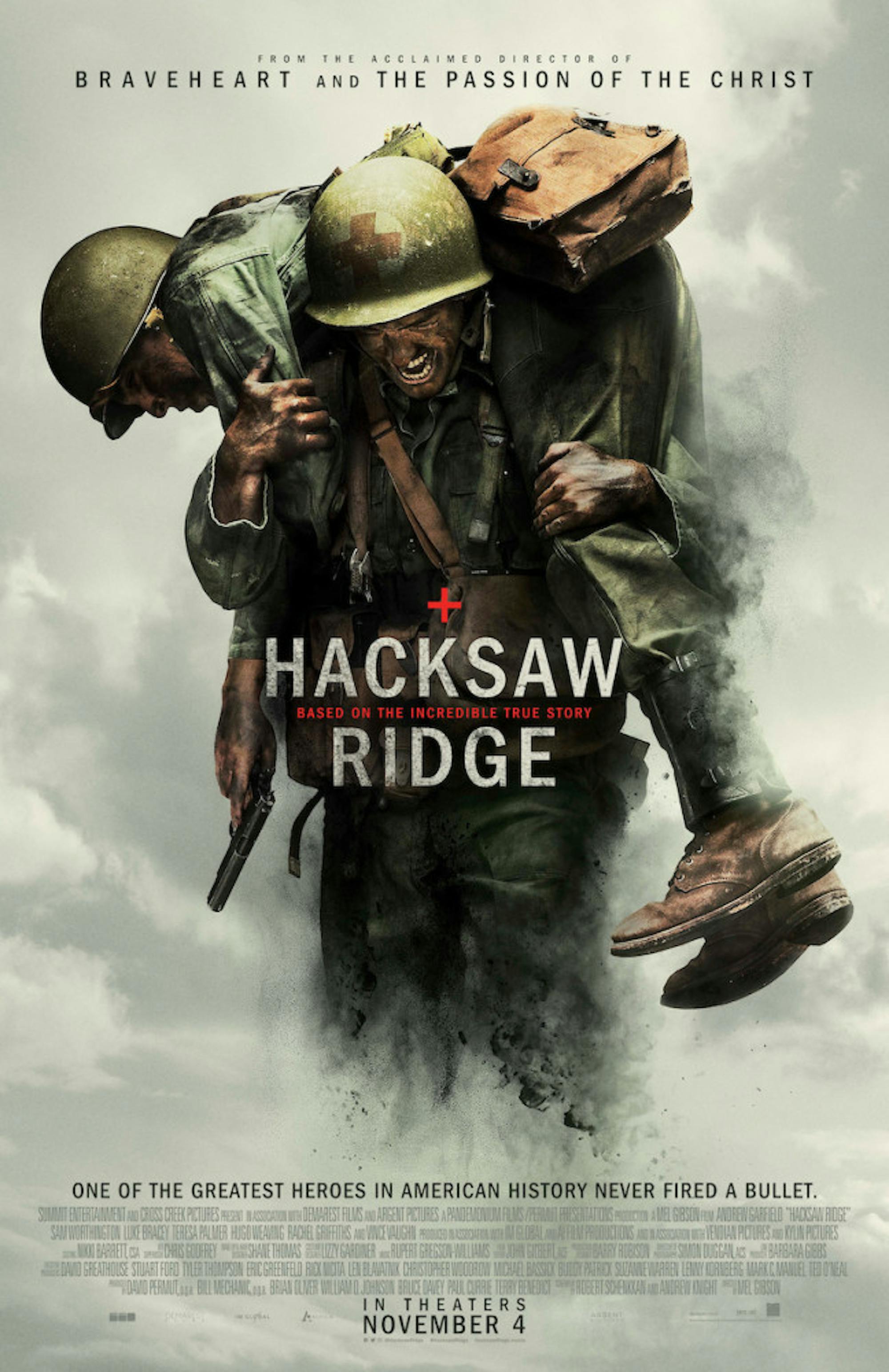

The new film is a chronicle of real-life World War II conscientious objector Desmond T. Doss (Andrew Garfield),a Seventh-day Adventist who refused to carry a weapon when he was drafted into the war.Doss was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actionsat the Battle of Okinawa, and any elaboration on his heroics is better left to Gibson.

First and foremost, this is a film about the courage of one’s convictions and the willingness to stand up for one’s religious beliefs, and Doss’ refusal to compromise his morals makes up the first half of the film.

It begins in Doss’ hometown of Lynchburg, Va., where his refusal to bear arms is cemented and where he meets his fiancée, nurse Dorothy Schutte (Teresa Palmer). Garfield is effective in these early scenes, his accent convincing and earnest grin charming both Dorothy and the audience. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Doss feels compelled to serve, later saying that when the Japanese attacked, “I took it personal.” His father Tom Doss, masterfully portrayed by Hugo Weaving, is furious. A World War I veteran, the elder Doss spends most of his time drinking and grieving for his fallen friends, wracked with survivor’s guilt and terrified that his son will become another gravestone for him to mourn. But as will become increasingly clear, Doss will not relent on anyone else's account.

Despite his wishes to serve as a medic, Doss is assigned to a rifle company and put under the charge of Sergeant Howell (Vince Vaughn).Writers Andrew Knight and Robert Schenkkan apparently couldn’t resist styling Doss’ boot camp experience after the iconic sequence in “Full Metal Jacket” (1987), and while Vaughn can’t muster R. Lee Ermey’s vulgar fury, he acquits himself well.

Howell, Doss’ fellow privates and the officer corps of the company all believe Doss is simply a coward, and they do their best to send him packing by teasing, hazing and beating him, but he perseveres and even a court-martial can’t deter him. These scenes, while well-paced individually, become cumbersome taken together. Well before Doss, incarcerated and awaiting court-martial, says to Dorothy, “I feel that my values are under attack and I don’t why,” the parallels to contemporary Christians’ perceptions of persecution are clear. Gibson does not traffic in subtlety, and his bludgeoning approach here, though well-crafted and acted, is still a bludgeon.

However, once Doss leaves Virginia behind and arrives at Okinawa, that same style becomes brutally effective. Doss and his comrades are tasked with taking the titular ridge, a sheer seaside cliff relentlessly defended by the Japanese. The Americans have been pushed back from the ridge several times, and Doss’ company is merely the latest mass of bodies to be sent into the meat grinder.

The initial battle sequence very nearly defies description. The Motion Picture Association of America has rated it R for “intense prolonged realistically graphic sequences of war violence including grisly bloody images.” This is a dramatic understatement. The opening D-Day sequence in “Saving Private Ryan” (1998), long considered the ultimate unflinching depiction of the hell of war, pales in comparison to what is on display here. That the gore never feels gratuitous is a testament to Gibson’s skill. Unlike the slick gunplay of “John Wick” (2014) or the gleeful badassery of “Mad Max: Fury Road” (2015), there is no “cool” factor involved. It’s clear that Gibson wanted to capture every terrifying aspect of not only the battle, but also its aftermath. The American soldiers are confronted both by Japanese defenders and the corpses of the fallen, rotting and infested by pests and vermin.

The violence is accurate and unabbreviated, and the results are shocking, conveying both the utter horror of battle and illuminating Doss’ bravery in repeatedly risking life and limb to aid his men. The only excess comes in Gibson’s inability to resist making Christlike comparisons, including a shot of Doss washing away the grime of war that evokes Jesus’ baptism, and an extended shot of Doss suspended in the air, a blunt-force version of the Ascension.

Despite its lack of nuance, Gibson’s comeback film is excellent and well worth it for those who identify with its religious themes and for those able to set aside the baggage of Gibson’s past.

'Hacksaw Ridge' is brutal, effective

Summary

4 Stars