For anyone who has interacted with Friedman over his last four years at Tufts, it likely does not come as a surprise that his latest dinner included such an impressive number of courses. Since his first year in South Hall, he has been creating dining experiences for friends, classmates and now students in his Experimental College course, "The Chemistry of Cooking: Science in the Kitchen," co-taught with Schwartz. Though a brief hiatus from big dinner events was necessary Friedman's sophomore year due to a lack of suitable cooking space in Wilson House, he picked the tradition up again the following fall. Now a senior, Friedman's style has definitely evolved through the years. Particularly, he explained, this year's dinners have been generally "much more casual" than past events -- including two taco nights, each with nearly 100 guests packed into his Somerville home. With only eleven guests, 13 was a return to "the more refined, more fine dining style" that he loves.

Driving with Friedman to Market Basket early Friday morning to pick up some staples for the dinner, the culinary connoisseur revealed that he only began his cooking ventures upon his arrival to college. Beforehand, his "strong background in art" focused on photography. However, according to Friedman, he has “loved food [his] whole life,” and came to view cooking as a natural extension of both the food world and the art world. Clearly someone who takes initiative, he has already progressed from working unpaid at a farm-to-table restaurant to being employed at Michelin-starred restaurants in Boston and New York.

Despite these fantastic experiences in restaurant kitchens, Friedman still calls the grocery store his “favorite place in the world.” Constantly picking up the food, seeing it, touching it … this is where Friedman says ideas start to “turn into reality." Visibly happy, he made his way through the aisles, pen behind ear, meticulously going over his printed-out list. And when two women standing nearby struggled to think of the name of a fruit, he cheerfully told them what they were looking for was a pomelo, pointing them in the right direction: “They’re right over there!”

[video width="1280" height="720" mp4="http://tuftsdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/a0219weekendervideo.mp4"][/video]

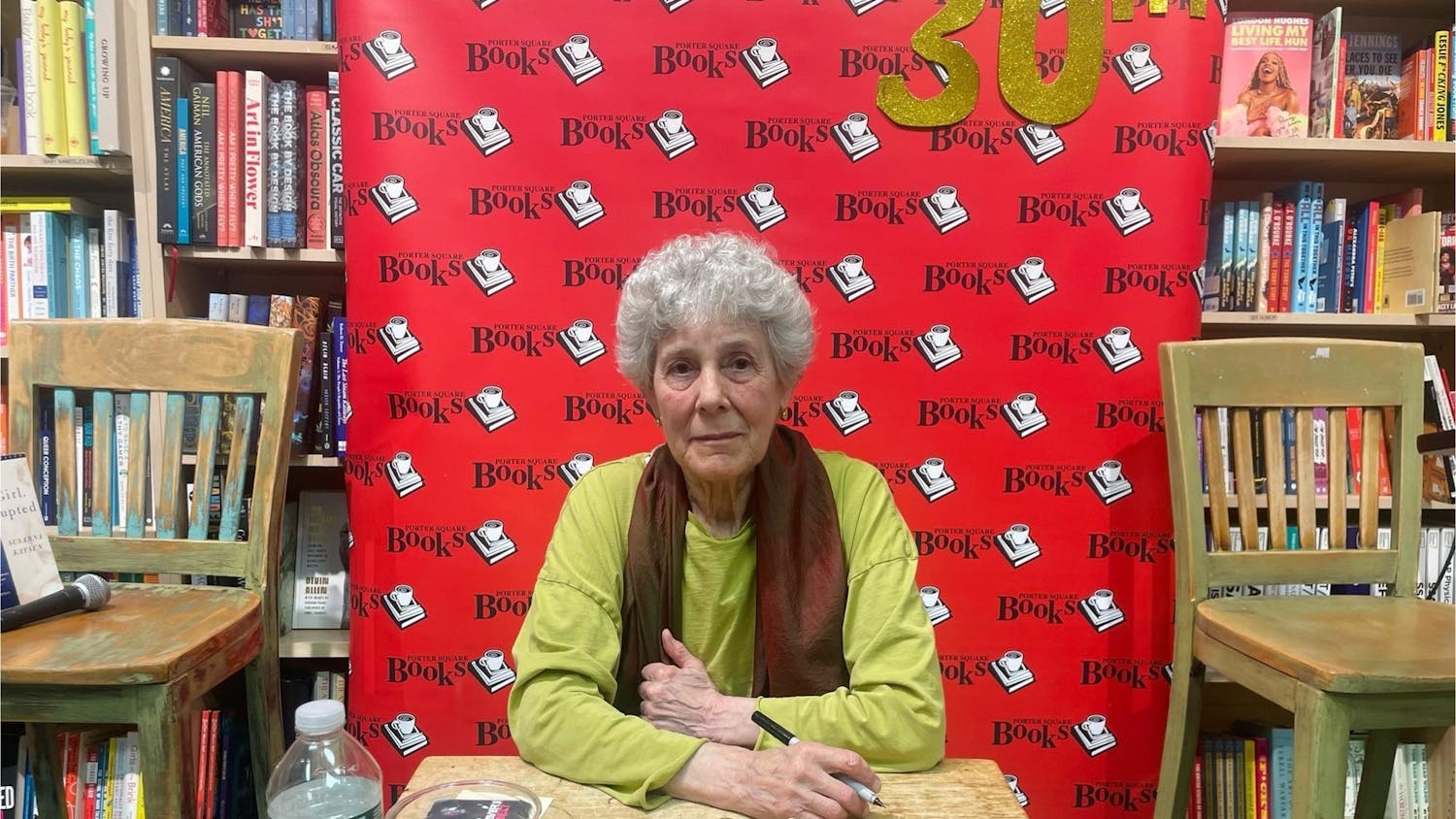

The Daily stopped by Theo’s house on Sunday afternoon to find him and some of his team working in the kitchen. Music played from a laptop on the table, with a slew of ingredients and knives neatly lined up alongside it. Notes written on pieces of paper denoting the ingredients in each course lined the wall under canvassed artwork and posters denoting species of fish, types of fruits and vegetables and the classic “Les Champignons.” If he was stressed, the lead chef hid it well as he danced around the kitchen.

Later in the evening, around 6:30 p.m., guests started arriving to Friedman’s house. Maya DeBellis, a first-year in Friedman’s Experimental College class, wandered into the kitchen with her fellow dinner guest, sophomore Julie Sanduski, and was playfully quizzed by Friedman on the latest chemistry-based cooking methods/concepts she had learned in the course: spherification and reverse spherification.

Once all of the guests were present, everyone was seated at a long dining room table, a giant number 13 decorated the chalkboard positioned behind the head of the table adding to the comfortable, eclectic feel.

Stepping out of the adjoining kitchen, Friedman welcomed everyone to the meal.

“Because it's kind of this test here, I want this to be a real conversation between us [the chefs] and you guys. I want to hear if something works for you … if something totally offends you, if you love something, if you hate something, if something sparks some emotion, some feeling, I want it all, please communicate back," Friedman said, by way of introduction. "I see food as a way to communicate and a way to express, so that's really what this is, it's a communication between us and you guys, and communication goes both ways.”

Shortly after, the first course -- a pea soup -- arrived. In no way, however, was this one’s average soup. Served in a vintage box flipped open by one of the chefs, each guest was invited to take out a small, chilled sphere the size of a Lindt chocolate to pop into their mouth in one bite, immediately bursting the delicious liquid center. As the dinner guests, called by Friedman “a diverse group of people … from different circles,” became more accustomed to one another, they also became accustomed to the beautiful presentations and experimental use of ingredients by the chefs throughout the night. Friedman's skill and that of the accompanying chefs was undeniable; almost every course was visually stunning, and met with a flurry of flashes from smartphones and independent cameras upon its placement on the table.

Well into the meal, first-year Daniel Navon, another student of Friedman and Schwartz, summarized the experience by noting the chefs' ability to “move all of the senses.” One primary example, a dish of cauliflower tartare, was served individually with an accompanying raisin curry on a beet meringue. The meringues appeared like leaves as they rested atop individual twisting pieces of metal extending from a wooden base, evoking the image of a small tree.

Guests were treated with the opportunity to talk candidly with the chefs after the whole meal, offering praise and constructive feedback. One of the most discussed dishes was the Adult Candy Bar, which involved a chicken liver pate served in a dark chocolate mold. As a guest very fond of cooking herself, Sanduski called the dish “a risk."

"It was an experiment … and it was executed perfectly,” Sanduski said. And while the majority of guests seemed to enjoy the dish, they also offered suggestions such as presenting the unique flavor combination in a different form.

Far from being taken aback, Friedman welcomed their responses; this feedback was exactly what he wanted.

The rest of Friedman's semester will be dedicated to a senior American Studies capstone project, an ambitious 20 course meal, for which he plans on “going back and reworking these dishes, testing … a bunch of new ones out.

"I’m going to try to look at it through the lens of the dinners as a performance piece and the paper as an artist’s statement like you would see in a gallery exhibition,” he said.

This artist’s perspective echoes what Friedman was thinking on the Market Basket visit.

"I try to scan my memory and there's nothing that I've eaten that I don't like," Friedman explained. "I know it sounds kind of silly to say, but in a way I kind of look at food and flavors as a painter might colors … I've never heard a painter say they don't like blue. If it's used in the right way, I think everything has power.”

And truly, the power of Friedman’s food to captivate his audience, the guests at 13, was palpable.

"To hear everyone talking and having a good time, and then silence when we brought the food out … that was amazing, it was great, to be able to bring people together like that," Watterson said.

Schwartz shared a similar sentiment: “Cooking brings people together, eating brings people together, because it's just about being in a time and spot. You're not thinking about anything besides what you're doing right now and who you're doing it with."

The hours of work — “about 18 hours on Friday, 19 hours yesterday, and …another 18 on Sunday, according to Friedman — stand as a testament to the chefs’ passion. Exhausted after the weekend, but clearly feeling fulfilled, Friedman mused on this subject.

“For me, I don’t even see it as passion; I feel like it’s a necessity … people say, ‘Oh, I express myself through painting,’ dance, or something like that … I really use this [cooking] as a way to communicate.”

Passion or no, it’s a drive for which Friedman seems grateful, and is lucky for students fortunate enough to collaborate with him. And, of course, lucky for those who taste the fruits of his “necessity”: cooking.