Taking place in the early 1860s, during the beginning years of the Civil War, Suzan-Lori Parks’ new work “Father Comes Home From the Wars (Parts 1, 2 & 3)” (2014) is a throwback of epic proportions. The production is actually comprised of nine parts in total -- the next six plays are still to come. The play touches issues past, present and seemingly eternal as Ms. Parks revivifies traditional ancient Greek theater with her use of classic devices, historical narrative and colorful contemporary dialogue.

The production at the American Repertory Theater, directed by Jo Bonney (who also directed the production in New York for the Public Theater), is serious, scathing, beautiful and funny all at once. With no single aspect of the production elevated in quality above other elements, the play "Father Comes Home from the Wars" is succinctly an overall masterpiece.

The play opens in 1862, somewhere in Texas, at the start of the war. The group who sings “Chorus of Less Than Desirable Slaves” (Charlie Hudson III, Julian Rozzell Jr., Tonye Patano and Jacob Ming-Trent) is taking bets on whether Hero (Benton Greene), the as-yet-unseen protagonist, will join their slaveowner, Colonel (Ken Marks), on the front lines of the Confederacy. Each of the four chorus members gives his or her reasoning as to why they think Hero will or will not go -- the exchanges are entertaining, if drawn out.

The play picks up steam with the revelation of the slaveowner's promise to Hero: Colonel will give Hero his freedom in exchange for Hero's assistance in serving the colonel on the front lines of the Confederacy in the war. Hero’s decision to help the Confederacy is dizzyingly ironic, but not unfounded, especially because Hero fears freedom more than he desires it. There is a greater emphasis on the psychological, rather than the physical, atrocities of slavery throughout the play. The entirety of Part 1 resolves in a flash, however, with Hero departing more as antihero than hero for his betrayal of Homer (Sekou Laidlow), another slave and a friend. The incident illuminates just how severely servitude has twisted Hero's moral compass.

Part 2 commences with Colonel, a colonel in the rebel army, relaxing by a fire while a Union soldier (Michael Crane) sits captive in a makeshift cage; Hero meanwhile is offstage gathering wood for the fire. At one point, the colonel says, "I am grateful every day that God made me white," going on to enumerate the advantages afforded him by his race. The relevance of Colonel's monologue to recent events is part of the beauty and power of this play, which flawlessly interweaves past and present -- try thinking of a more poignant and cringe-worthy way to elucidate white privilege to audiences than having a Confederate nutcase enumerate the extensiveness of that privilege to them, in monologue form.

The final part of this installation in the "Father Comes Home From the Wars” odyssey brings the audience back to Texas, now in 1863. The characters who comprised the Chorus from Part 1 have left the narrative, and new characters (played by the same actors) make up the new chorus labeled as “The Runaway Slaves."These runaway slaves are on their way north and hope to bring Homer and Penny (Jenny Jules), the lover whom Hero leaves behind when he goes to war, with them.

Allusions to Homer’s “Odyssey” run rampant throughout Parts 1 and 3. Hero, in Part 3, changes his name to Ulysses – a reference both to Odysseus (Ulysses is the Roman version of the name) and to the Union commanding general Ulysses S. Grant.Odd-see, a play on the word "Odyssey," is the name of Hero’s hilarious talking dog, who plays a pivotal role in heralding his master’s return in the same way as the dog in Homer's “Odyssey.”

For all the references, the play is not reverential. The dialogue is peppered with contemporary slang, and the actors, tailored in a mashup of period and modern clothing, make full effect of these moments. To wit, the fourth wall is hardly even a consideration -- both literally and figuratively, it does not exist in this play.

The cast keeps this play, which runs nearly three hours, moving at near breakneck speed for much of the time. Ming-Trent brings outstanding energy to the role of Odyssey Dog, delivering lines that are equal parts harsh criticism and comedic retort with aplomb. Ms. Jules, who breaks hearts with her performance in Part 3, is also a highlight of the production.

The story wraps up neatly at the end -- if the outcome is not surprising, then the motivations that lead the character to that concluding point are -- and could very well stand on its own without the next six parts. Like any show with a stellar opening, however, “Father Comes Home From the Wars (Parts 1, 2 & 3)” makes you want to see the rest of the volumes in the series; it’s that good.

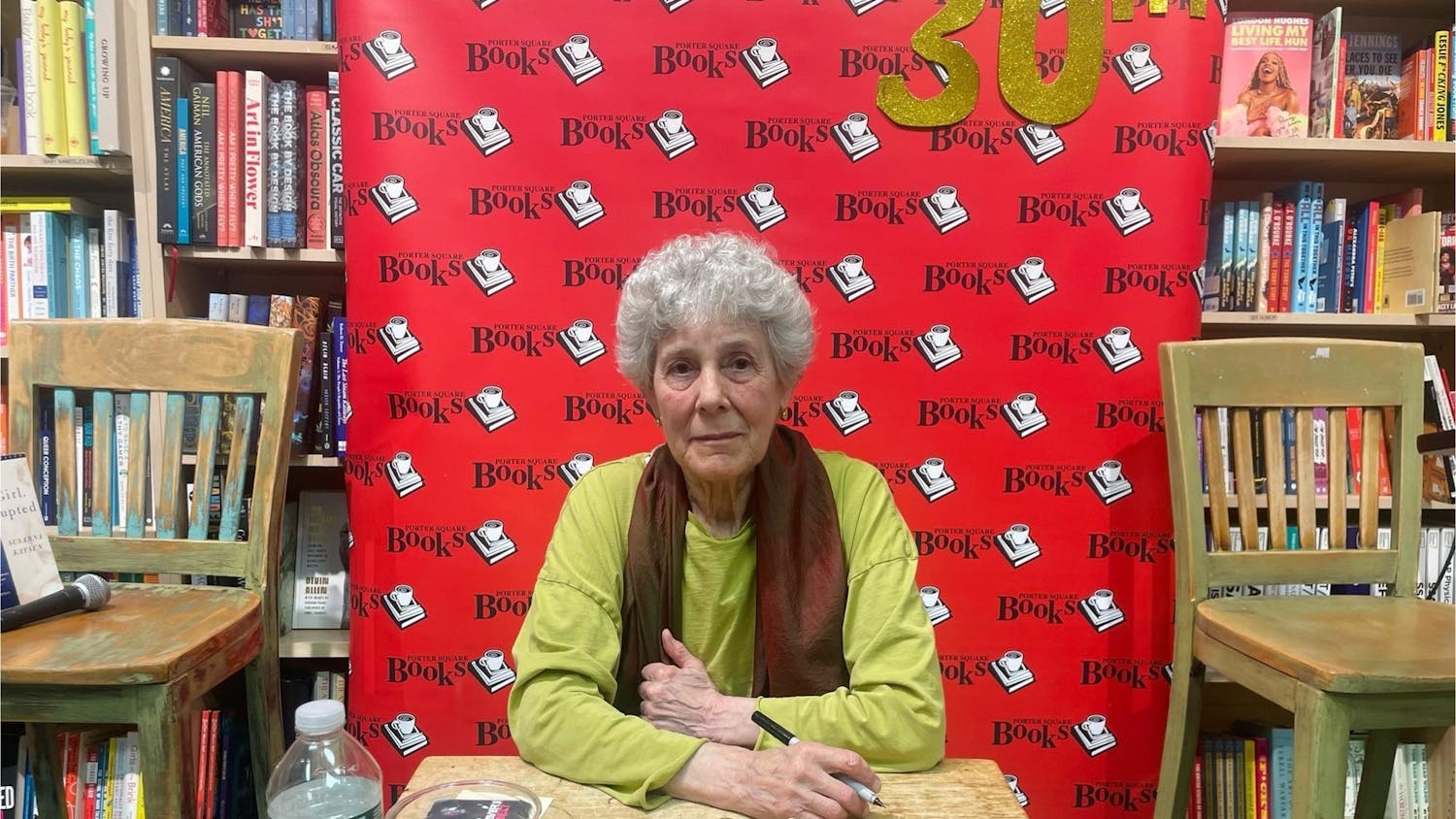

“Father Comes Home From the Wars (Parts 1, 2 & 3),” written by Suzan-Lori Parks and directed by Jo Bonney, is playing at the American Repertory Theater through March 1. Tickets are $25 for students with a valid student I.D.

'Father Comes Home From the Wars' powerfully revives Greek theatrical devices

"Part 1: A Measure of a Man" of "Father Comes Home From the Wars" follows Benton Greene as Hero as he struggles to decide whether to go to war for the Confederacy to win his freedom from slavery.

Summary

Like any show with a stellar opening, “Father Comes Home From the Wars (Parts 1, 2 & 3)” makes you want to see the rest of volumes in the series; it’s that good.

4.5 Stars