Science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke once wrote, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

Magic, art or science? Film photography blurs the lines between these categories and creates permanent images from nothing but light and chemicals. This process feels like magic, even when you do it yourself from start to finish. So let’s look behind the curtain and learn how this chemical process comes to life.

The word “photography” originates from the Greek words “phos,” meaning light, and “graphe,” meaning drawing. Thus, in its most simplistic form, photography is drawing with light.

This was especially true for the precursor technology to photography: a camera obscura. This device used light coming through a pinhole into a dark chamber to project images. The first known use of such technology was in China in the fifth century B.C.

From this point until the 17th century, the camera obscura was used almost exclusively for scientific purposes such as tracking time and observing solar eclipses without damaging onlookers’ eyes. It was a magical way in which humans started to see the world through something other than their own eyes.

A drawing of a camera obscura is pictured.

It is at this point that artists took hold of the camera obscura, adding a lens and mirror, to project images with the purpose of tracing and painting them. And so, early photography transitioned from being a scientific method to an artistic one.

The next big change came with the discovery of photosensitive chemicals in the 19th century, which gave photographers the ability to preserve projected images on glass and metal plates. Thus, the photograph as we know it today was born.

These photosensitive chemicals catapulted photography in a new direction and now make up the magic that is modern film photography. They are used at every step of film photography, from initial exposure all the way to final printing.

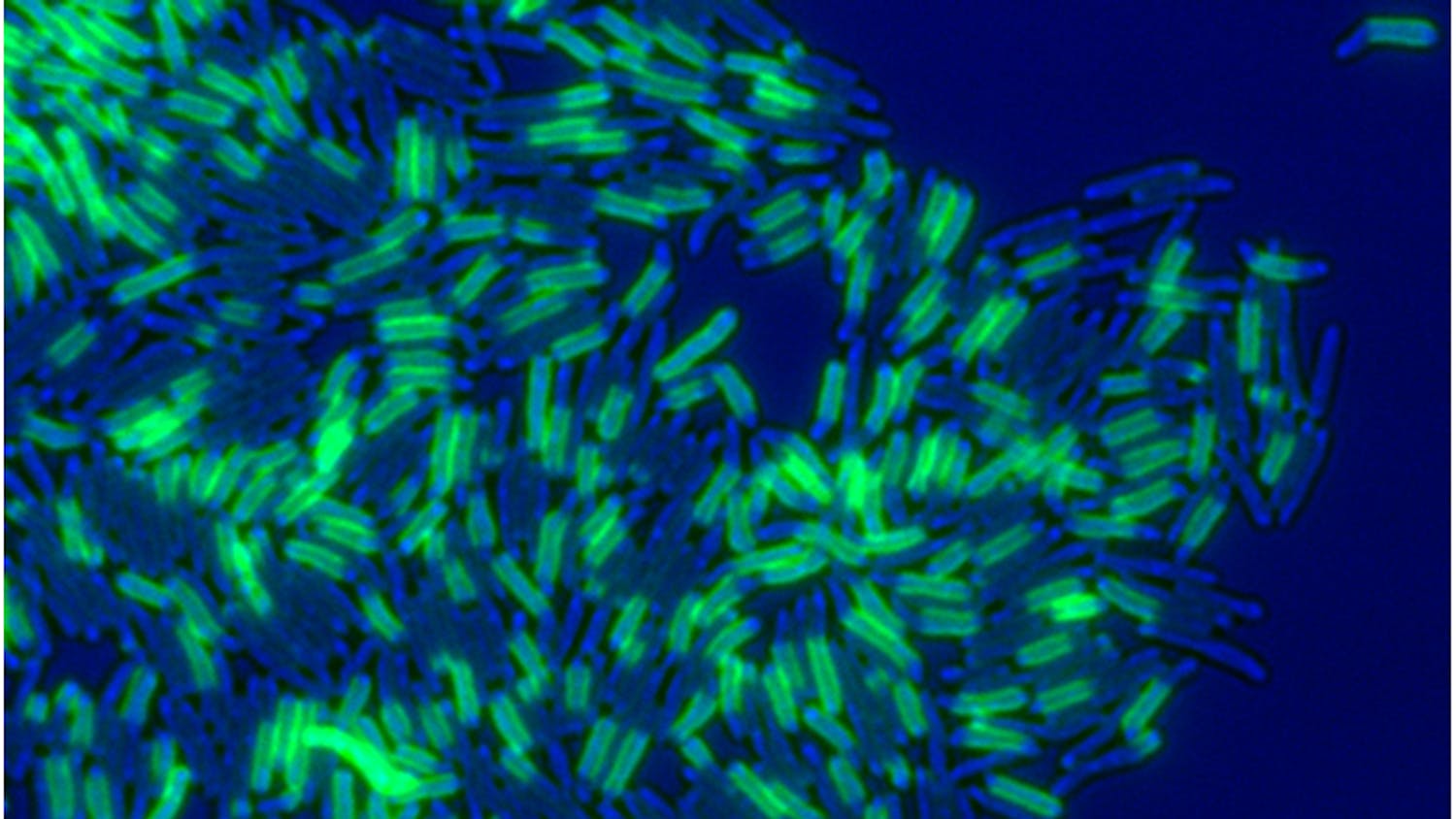

The first step to photography of any kind is exposure. In film photography, this is when the shutter of the camera opens up to outside light for a calculated amount of time, exposing the film inside the camera. This film is loaded with silver halides, which are chemical compounds containing silver bonded to either bromine or chlorine.

When these halides are exposed to light, a reduction reaction takes place, separating the silver atoms from the bromine or chlorine. This process creates an invisible image on the film, which will become visible through the second chemical process of film photography: development.

In the development process, film is removed from the camera and placed into a light-safe canister while in a completely lightless room. Then, the reduction reaction of the silver halides is put into hyperspeed using organic compounds poured into the light-safe container. This makes the image on film much more visible and defines its contrast.

When the reduction reactions have gone on long enough to produce a visible image, the developing solution is dumped, and a stopping solution is added. This solution most usually contains acetic acid, which halts the silver reduction reactions and freezes the development of the image.

From there, the film needs to be fixed — aka preserved in its final state of development — so that it doesn't degrade over time. This is done by removing all excess halides from the film using a sodium thiosulfate solution, which reacts with the leftover halides and makes them soluble in water.

Finally, all of these processes culminate in a visible image on film that can be rinsed in water to remove all excess chemistry. This washing stage is followed by the drying of film in a heated drying cabinet.

This first exposure and development process yields a roll of negative images on film. In order to get positive images printed on paper, you have to do the whole process again in a slightly different way. This is referred to as silver halide printing.

Something important to note is that where film is photosensitive to all forms of light, photo paper is sensitive to most wavelengths of light but not all. This allows the darkroom of a film lab to be lit using a safelight, which fits into the non-sensitive part of the light spectrum.

Under the reddish amber glow of the safelight, the printing process takes place. First, the film is loaded into an enlarger, which is a machine that projects light through the negative image film in timed increments. The light travels through the negative image film, casting a positive image on the table below.

This leads us to the first step of the printing process, where photosensitive paper is placed below the enlarger and exposed to a timed increment of light. This causes the same reduction reactions of silver halide as in the exposure process of the original film.

In a manner similar to the film, the photo paper is then submerged in development, stopping, fixing and washing solutions. This yields a visible, positive image better known as a printed photograph.

And so now you know all the magicians’ tricks when it comes to photography. But does that really make this technology any less magical?