Until very recently, it was believed that Alzheimer’s disease, a progressive neurological disease that causes memory loss, develops from a combination of intrinsic genetic and environmental risk factors. However, a January 2024 study suggests that some individuals may have acquired it from contaminated treatments earlier in life. This study identified five individuals who received human growth hormone treatment over 40 years ago and eventually developed early-onset Alzheimer’s.

According to an article in the Guardian, at least 1,848 people were treated using human growth hormone from the pituitary glands of cadavers in the UK during the 20th century. However, the practice was discontinued after multiple patients died as a result of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. CJD is a neurodegenerative disorder that can result in dementia and potentially death, with a life expectancy of only one to two years after diagnosis.

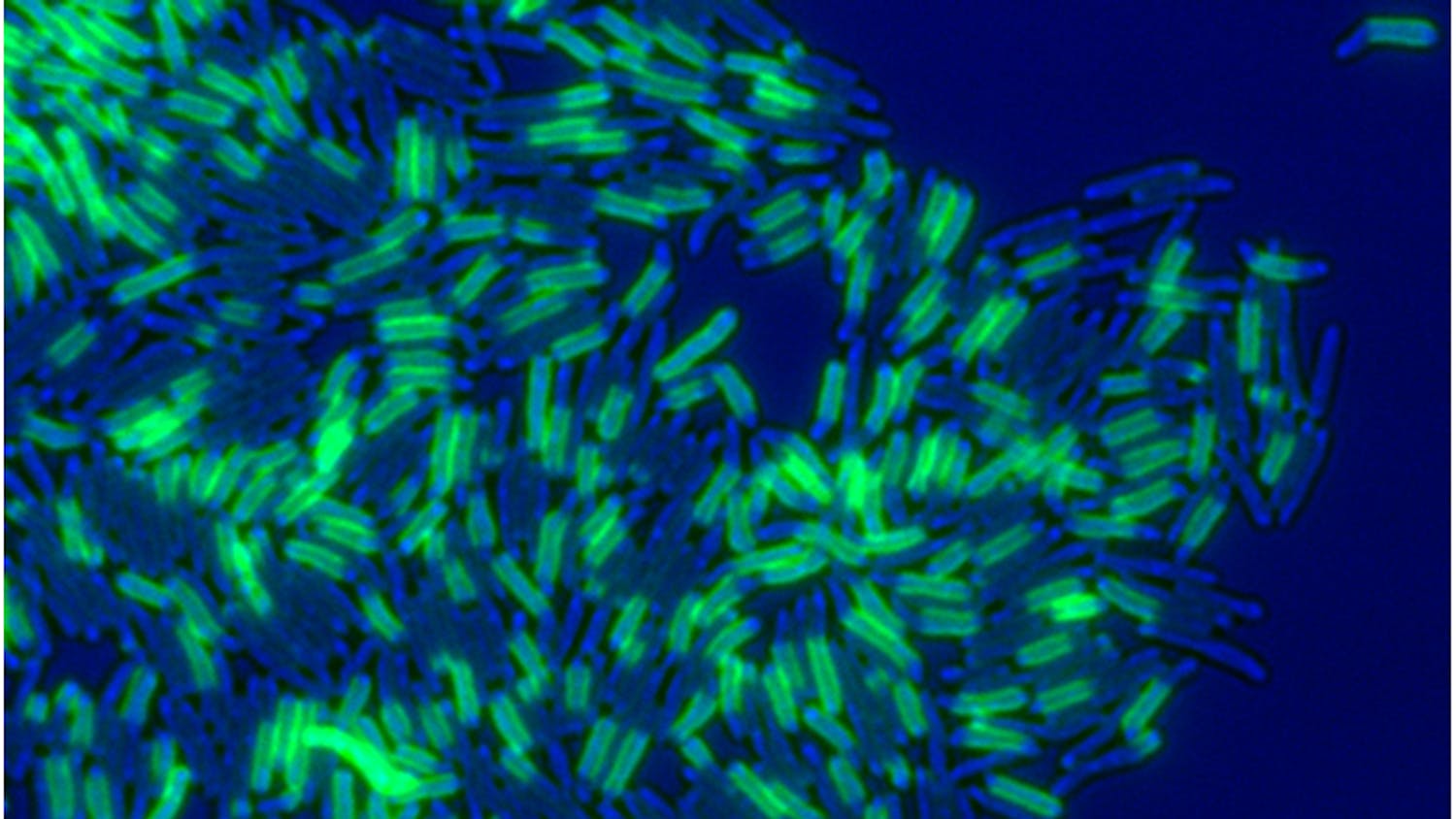

Researchers suggest that the likely reason for this spread is because the growth hormones were contaminated with infectious proteins known as prions. Prions are misfolded proteins that influence functioning proteins to fold abnormally. They are known to potentially cause diseases that can propagate through infected brain tissue such as CJD and kuru. Kuru, like CJD, can cause neurodegenerative changes in the brain.

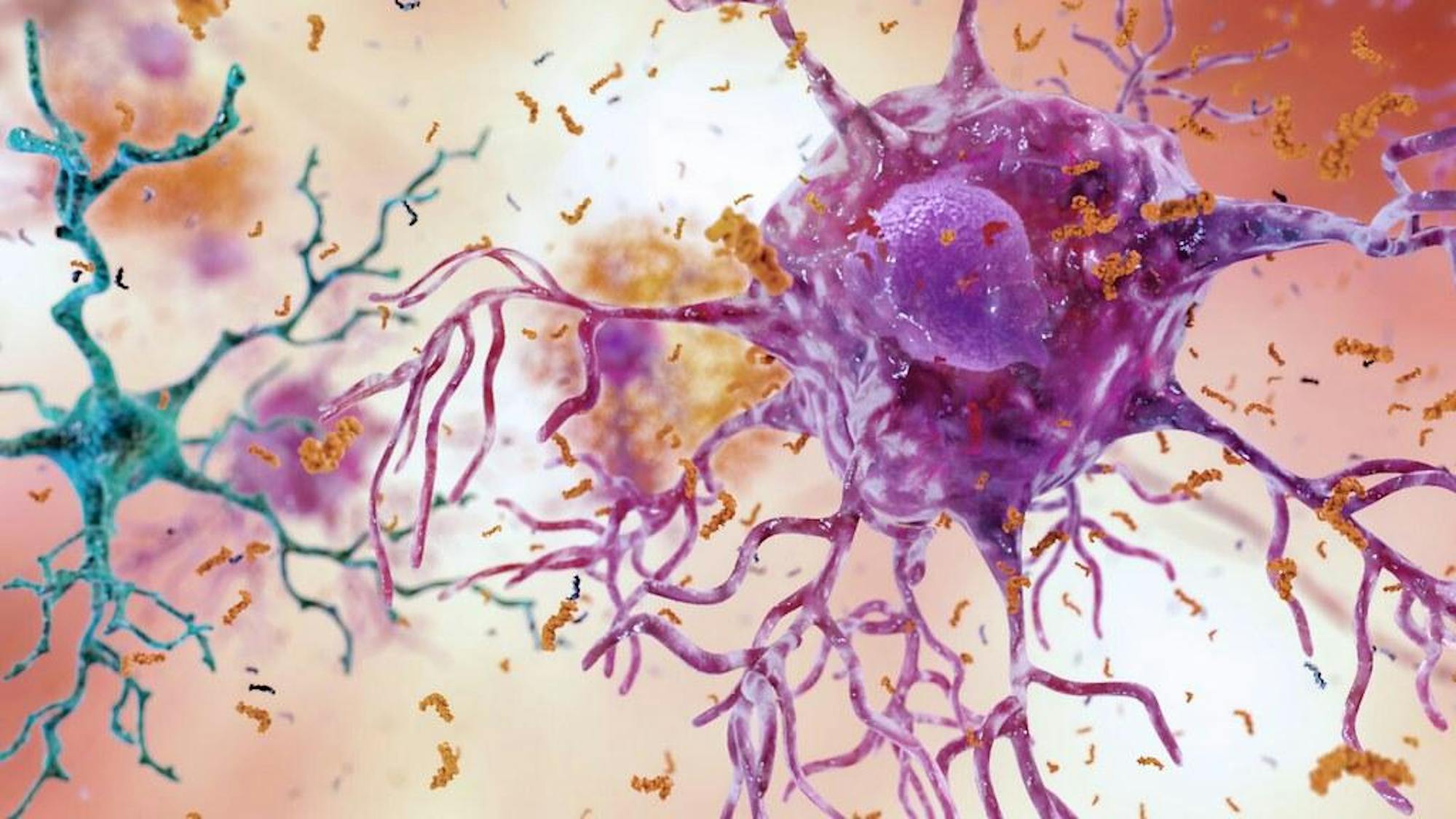

Some individuals from this study also contained amyloid-beta proteins in their brains, which are indicators of Alzheimer's disease. The researchers previously identified amyloid-beta proteins in the contaminated batches of growth hormone. Misfolding and aggregation of amyloid-beta proteins in the brain have been linked to the cascade reaction involved in Alzheimer’s disease.

However, most experts emphasize that there is still no concrete evidence that the disease can be passed through basic human interaction, and agree that this study reveals the result of poor infection control in previous medical practices.

Professor John Collinge, the lead author of the study, told the Independent, “There is no suggestion whatsoever that Alzheimer’s disease can be transmitted between individuals during activities of daily life.”

In regards to future endeavors, Professor Bart De Stropper of the U.K. Dementia Research Institute at University College London said, “This is a very interesting study providing further insight on the risk of the transmissible form of amyloid beta.”

Moreover, Collinge added, “However, the recognition of transmission of amyloid-beta pathology in these rare situations should lead us to review measures to prevent accidental transmission via other medical or surgical procedures, in order to prevent such cases from occurring in future.”

While the conclusion that Alzheimer’s does not spread through contagion is a sigh of relief, delving deeper into the potential repercussions of beta-amyloid plaques is key to furthering the field of Alzheimer’s research.