Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series on Tufts’ tuition. Read the second part here.

It is no secret that Tufts is expensive. Tufts is the fifth most expensive school in the country, with tuition for the 2023–24 school year being more than $66,000, well above the national average for private colleges, which is approximately $42,000.

This astronomical price tag has numerous implications. For one, it limits the socioeconomic diversity of our student body. A 2017 study found that Tufts is ranked 10th in the nation for colleges with the highest median family income and 50% of Tufts students come from the top 5%. Only 44% of Tufts students are on financial aid, versus 55% at Harvard or 56% at Amherst. These stats are to be expected, with tuition as high as it is. There are certainly many qualified students who would love to attend Tufts, but aren’t here because they simply can’t afford it. Our campus is missing their perspectives and contributions.

In addition, our costly tuition forces many Tufts students to take on more loans — last year 20% of Tufts students were receiving federal student loans. This is through a program that the U.S. Senate declared to be “plagued by fraud and abuse.” Student loan debt is notoriously difficult to pay off, an issue that is compounded by high interest rates. It is also known to disproportionately affect Black borrowers and can have a deleterious effect on borrowers’ mental health.

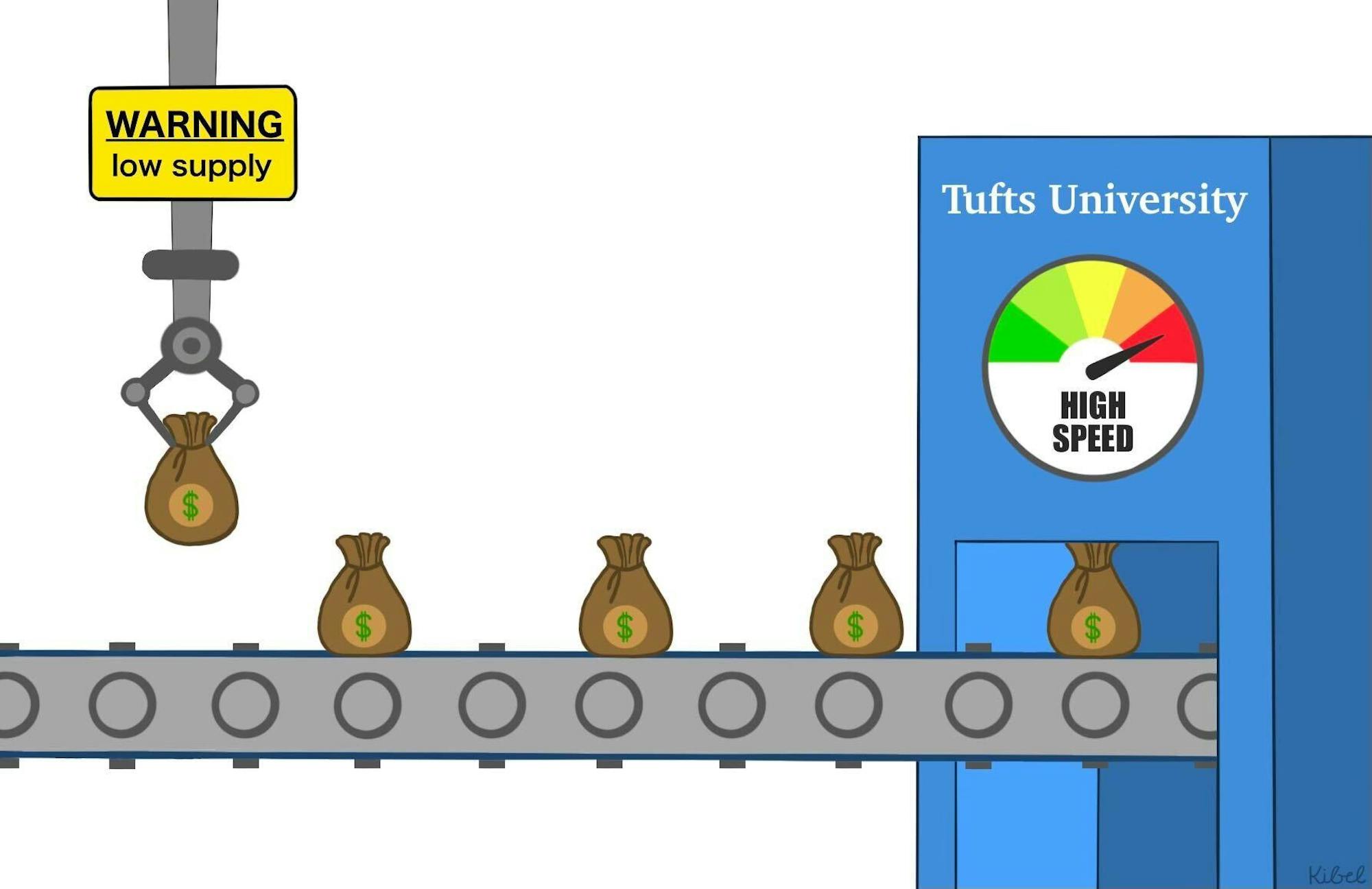

Unfortunately, Tufts cannot lower tuition, ease their students’ reliance on loans or increase its socioeconomic diversity as long as the university continues to rely heavily on tuition as a source of income. Tuition and fees make up 51.9% of Tufts’ operating revenue — and 59% of Arts, Sciences and Engineering revenue — versus 30% for Amherst and only 22% for Harvard. This difference between Tufts and our peer institutions reveals why Tufts ranks so high on tuition and so low on measures of social mobility. While President Kumar has previously told the Daily that “how well we are doing as a driver of our students’ social mobility” is important to his administration, the Wall Street Journal ranks Tufts 391 out of 400 colleges on this measure. It is clear that Tufts has a long way to go to improve this statistic.

This reliance on tuition also drives overenrollment, an issue which has led to numerous negative student outcomes including the housing problems; Consequences include Tufts students living in a hotel and modular housing units in recent years. In fact, as Patrick Collins, Tufts’ executive director of media relations, told the Daily in 2022, “Growth in enrollment … will put a Tufts education within reach of more students, solidify the financial footing of our undergraduate schools and programs and provide for the kinds of facilities needed to support world-class teaching and research.” Essentially, Tufts needs tuition money from more students, regardless of whether the university’s infrastructure can adequately provide for them.

Where exactly do these tuition dollars go? To answer this, we spoke with Jim Hurley, vice president for finance and treasurer, Mike Howard, executive vice president and Craig Smith, chief investment officer. AS&E student costs are estimated at around $48,000 per student, while the average net tuition for AS&E students after financial aid is $41,000.

Tuition covers about 75% of the cost per student at the university, with the remaining 25% coming from the endowment, gifts and other sources. What are these student costs? They include academic costs such as faculty compensation and departmental expenses, which make up about 55%, as well as space costs and institutional support. However, the student cost figure is about 30% lower than full tuition, meaning that money from students who pay full or higher than average tuition supports the university beyond their own cost of attendance.

The primary reason that Tufts relies so heavily on tuition is that we are underendowed compared to our peers. In other words, we have a much lower ratio of endowment to number of full-time students than many of our peer institutions, including the University of Pennsylvania, Northwestern and Brown. Margot Biggin, executive director of the University Advancement division, provided an explanation for the smaller endowment size at a TCU-hosted University Budget & Fundraising Town Hall in 2019: “We have been seriously fundraising the past 25 years, many of [our peer] schools have been doing it for decades. Making up for that lost time is a very tough thing to do.”

This reasoning is not sufficient: 25 years is two-and-a-half decades. Believe it or not, way back in 2001, the then-executive administrative dean of finance, budget and personnel pointed out the issue: “We are at a disadvantage because of the size of our endowment. The long-term issue is that we do need to raise money.” Twenty-two years later, the issue remains the same.

Tufts’ high price has numerous negative ramifications for the Tufts community. This can’t change as long as we remain underendowed and heavily rely on tuition as a source of revenue.