Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, affecting an estimated 6.7 million Americans. Earlier in the year, biotechnology companies Eisai and Biogen made a significant breakthrough in the landscape of pharmaceuticals, resulting in Lecanemab, also known by the brand name Leqembi, a new prescription medication designed to decelerate cognitive decline associated with the disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is a condition primarily found in adults over 65 that steadily impairs memory and mental function. It became widely known through a report in Germany on Nov. 3, 1906 by the eponymous psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer, who had been observing a 50-year-old woman with a strange set of symptoms, including memory disturbances, confusion and aggression. The condition developed rapidly and claimed her life only five years later. Alzheimer examined slides of the woman’s brain tissue and noted distinctive plaques as well as protein accumulations on her brain cells called neurofibrillary tangles.

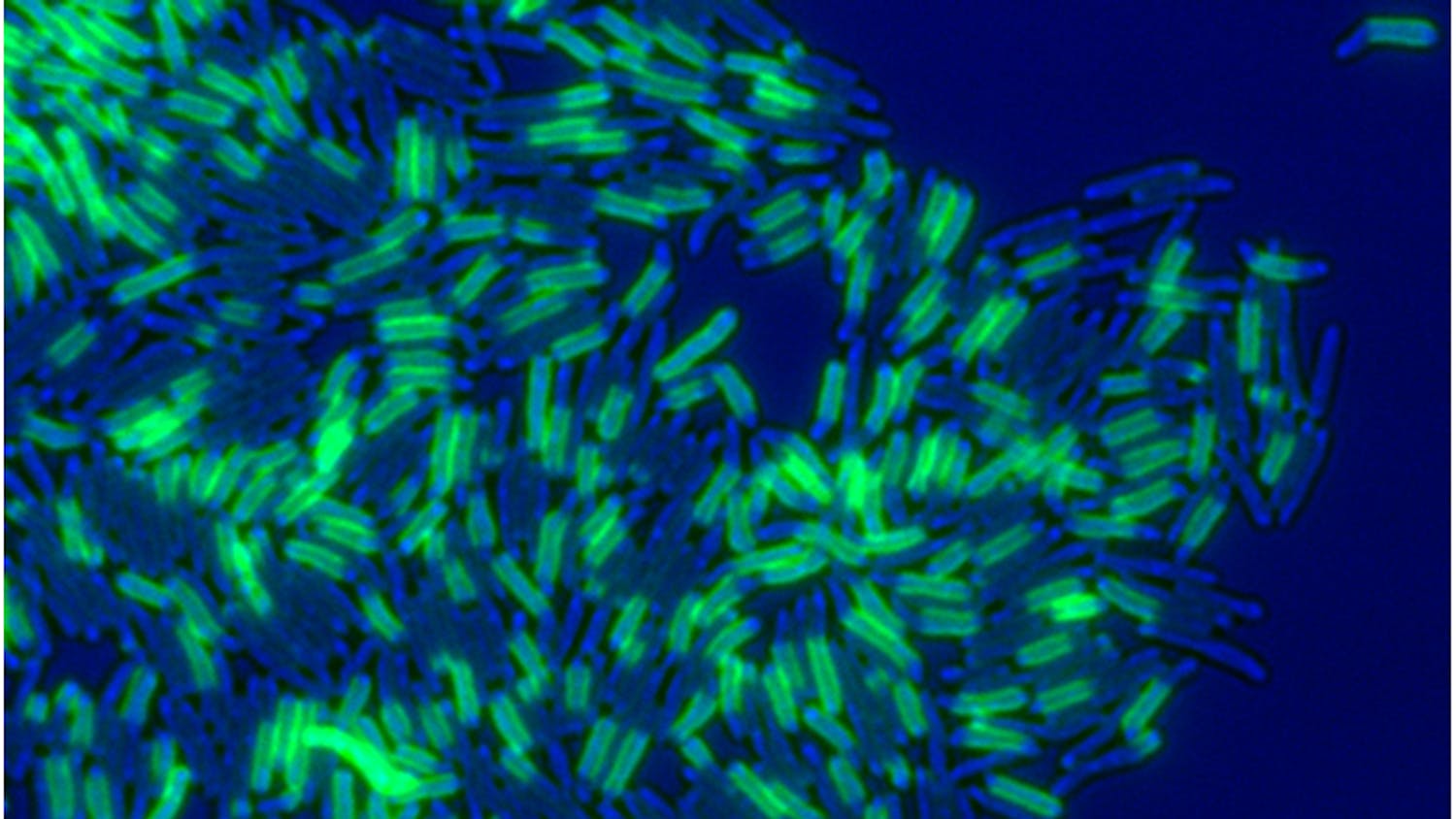

Plaques are the hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. The National Institute on Aging explains these plaques are made of beta-amyloid proteins that consist of multiple forms, with beta-amyloid 42 being considered especially deleterious. Beta-amyloid proteins clump between neurons, disrupting cell functioning and memory. Neurofibrillary tangles, a buildup of a protein called tau on neurons, also affect memory processes. Once a certain amount of beta-amyloid plaques collect on the brain, tau proteins swiftly propagate throughout the brain. Notably, most types of Alzheimer’s are not directly linked to a single genetic cause. Although multiple genes have been linked to the condition, factors such as smoking, diet and exercise can also affect one’s chances of developing Alzheimer’s.

As such, Leqembi is not a complete treatment but rather a measure to improve life expectancy and quality of life for diagnosed patients. Infused intravenously every two weeks, Leqembi targets the amyloid plaques, effectively preserving cognitive function for a longer time, according to Forbes. The drug has been approved in part because it does not have many alarming side effects. At most, Leqembi was found in trials to occasionally cause an amyloid-related imaging abnormality, which is essentially inflammation in certain brain regions. This side effect can manifest as ARIA-E (brain swelling due to fluid collecting) or ARIA-H (bleeding in the brain).

Notably, Leqembi only treats amyloid-beta plaques, which are only one piece of the Alzheimer’s puzzle. However, Michael Irizarry, Eisai’s head of Alzheimer’s research, told BioSpace that the company is currently developing the E2814 drug that is targeting tau, the protein that leads to neurofibrillary tangles. In theory, Leqembi can be combined with this tau-targeting medication to combat both plaques and tangles, potentially slowing cognitive decline even further.

The Food and Drug Administration accelerated Leqembi’s approval on Jan. 6. Through this method, the FDA can “approve drugs for serious conditions where there is an unmet medical need, based on clinical data demonstrating the drug’s effect.”

However, it was not until July 6 that the FDA granted Leqembi standard approval, meaning that the U.S. Medicare health plan for patients over 65 could have broader coverage for the drug, which carries a hefty price tag of $26,500 a year. While Medicare can cover around 80% of the price, that still leaves about $5,000 for Alzheimer’s patients and their caregivers to pay annually. Although Eisai has support programs to help with the cost, it is not fully clear how much they will cover or if the funds they offer will be enough to diminish the economic burden on patients and caregivers.

Regardless of the cost, a larger concern is that Leqembi may not benefit all Alzheimer’s patients equally: Alzheimer’s — and dementia more generally — may afflict Black Americans for different reasons than it does white Americans on average. An NBC article writes that elderly Black Americans have two times the dementia rate as elderly white Americans. Despite this, 49% of Black volunteers did not qualify for the clinical trials because they did not have enough amyloid-beta protein in their brains to be considered.

This disparity not only exists between Black and white Americans, but also between Black and Hispanic Americans. Even though 55% of Hispanic volunteers did not meet screening requirements, they made up 22.5% of Eisai’s U.S. 947-person Leqembi trial — an overrepresentation of Hispanics in the broader U.S. population — while only 4.5% of participants were Black — a brazen underrepresentation of the population that is most affected by Alzheimer’s in the United States. Eisai reports they are currently looking into why such a large number of Black volunteers were screened out of the trial.

Multiple studies are finding that systemic racism and the resulting socioeconomic inequality, a disparity that affects access to medical care, better quality of life and exposure to environmental factors likely have a hand in these biological differences between American racial groups. So, while Leqembi’s approval is an impressive contribution to the field of medicine, it is just the tipping point to fine-tuning treatments, investigating Alzheimer’s disease and dementia further and recognizing healthcare inequities in the United States and the world at large.