“History repeats itself, first as a tragedy, second as a farce.”

— Karl Marx

“According to housing director John Darcey … the university looked seriously into housing freshmen in nearby HOTELS (i.e. Sheraton Commander in Cambridge), or possibly purchasing new CONDOMINIUMS for the overflow. ‘We have the money to do it,’ he said.”

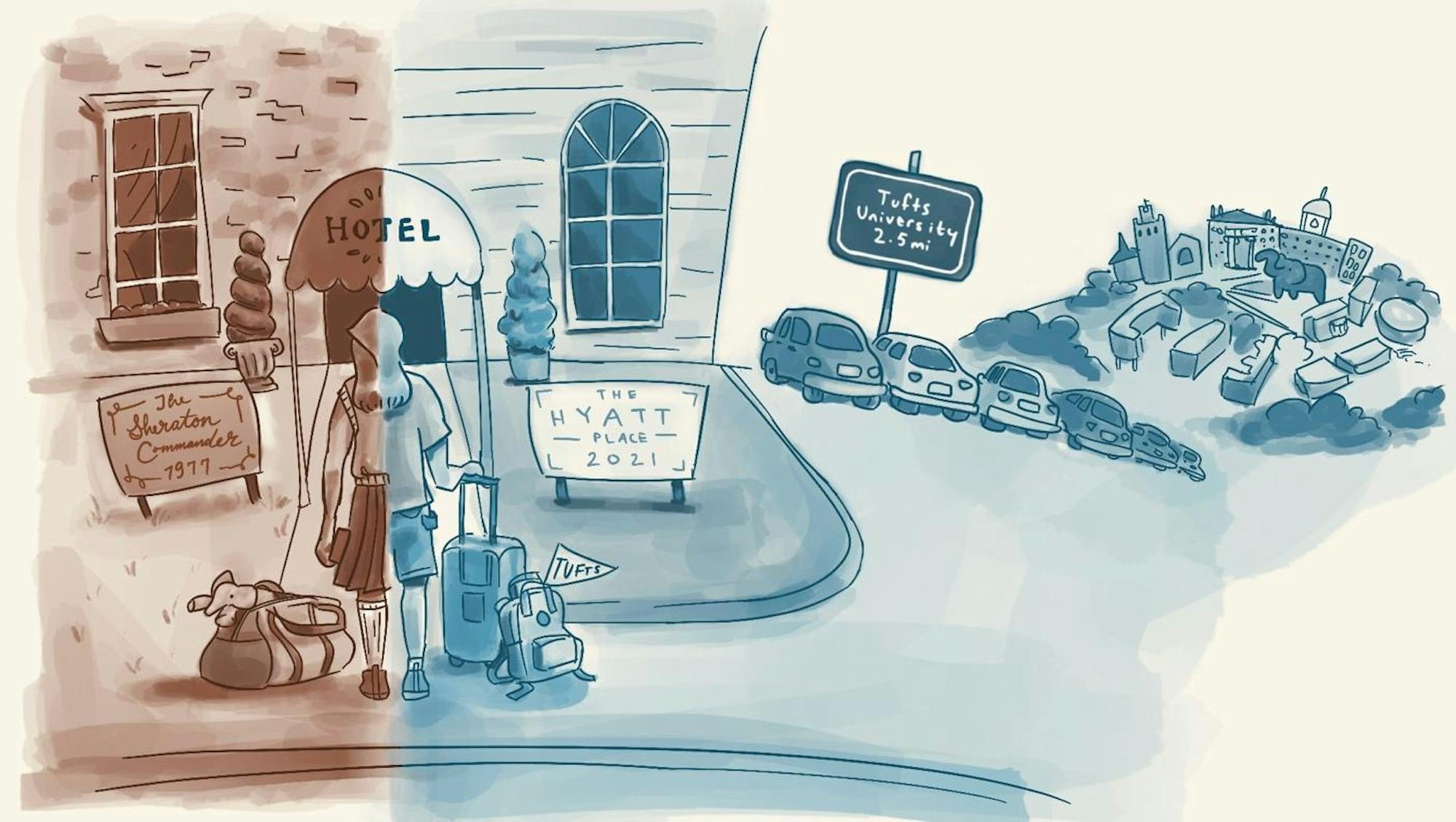

This quote from a Tufts Daily article appears to capture the Tufts housing crisis quite accurately. So would it surprise you that the quote above is from 1987? Tufts has been dealing with housing issues for decades and many of the root causes persist today. But to understand the true nature of the Tufts housing crisis, we have to go all the way back to 1977.

Jimmy Carter is President of the United States and Fleetwood Mac is relishing the success of “Rumors.” After a long day of classes and studying in the library, you decide to head back to your dorm for the evening. Instead of going to Haskell or Harleston like your friends, you have to travel 2.5 miles back to your dorm: the Sheraton Commander in Cambridge.

The 160 Tufts students who were forced to live in the Sheraton Commander in the fall of 1977 complained about the long commute to the Tufts campus. As the Harvard Crimson reported, the underlying issue was over-enrollment, a problem not unique to Tufts.

Despite valiant attempts to normalize hotel living, students were dealt another blow: On March 23, 1979, the Tufts Observer reported that over spring break, several rooms in the Commander were burglarized with around $3,500 worth of items stolen. Nonetheless, students continued to live in the Sheraton Commander through 1980.

Ten years after first housing students in the Sheraton Commander, Tufts faced another housing crisis. Doubles were converted into triples, causing rooms to feel overly cramped. An unnamed student explored the university’s infelicitous approach in “A Modest Proposal,” a Swiftian opinion piece (quoted at the beginning of this article) published in the Sept. 3, 1987 edition of the Tufts Daily. The author went on to propose converting upperclassmen on-campus housing to first-year housing so that “the entire freshman class can enjoy the healthful benefits of dorm life.”

In 2021, 100 freshmen lived in the Hyatt Place in Medford Square. Students expressed frustration with the unreliable shuttle and absence of community; however, when pressed on whether Tufts was in the midst of a housing crisis, Josh Hartman, then-senior director of residential life and learning, denied the allegation, citing other schools’ housing issues as well as the use of hotel space as a “common solution in these situations.” Of course, Hartman’s assertion is intellectually dishonest. He claims that hotel housing is appropriate because other universities do the same, but disregarded any potential impact on students. (As an aside, I hope Hartman does not assume responsibility for coaching the debate team any time soon.) Defaulting to hotel rooms to address a housing shortage is not a well thought out student-oriented solution. It is a quick fix built on years of institutional laziness.

For decades, Tufts has accepted more students than it can appropriately house in dorms, and a high experiential toll has been paid by the students affected. I am left wondering how university administrators sleep well at night in their expansive residential homes knowing that they’ve assigned students to sleep in hotel rooms, or for that matter, modular pre-fabricated boxes constructed on a tennis court.

Make no mistake: the Tufts housing office isn’t entirely to blame for this situation. The issue of housing at Tufts is also one of poor planning, and the problem is not just over-enrollment (whether intentional or due to failed algorithms), but a failure of governance.

History repeats itself. Tufts has experienced housing crises for more than 40 years. Whether renting out space in hotels, converting double rooms into triples or building makeshift structures on athletic spaces, there is no denying that Tufts’ housing situation is in dire straits. And yet, housing administrators deny it. Worst of all, after witnessing the problem for decades, administrators should have had the time to construct solutions. They did not do so.

The construction of new academic buildings before new dorms suggests Tufts leadership prioritized other matters over student living. This may satisfy some, but it borders on cruel, given the social impact on students, and the fact that such impact could have easily been avoided with proper planning and resource deployment.

The similarities between the housing of students in the Sheraton Commander in 1977 and in the Hyatt Place in 2021 are uncanny. Perhaps one can debate the precise causes of failure and who is responsible, but the facts on the ground compel the conclusion that Tufts has failed to provide adequate housing. At the end of the day, we need to more closely examine and change important elements of leadership and governance that impact students.