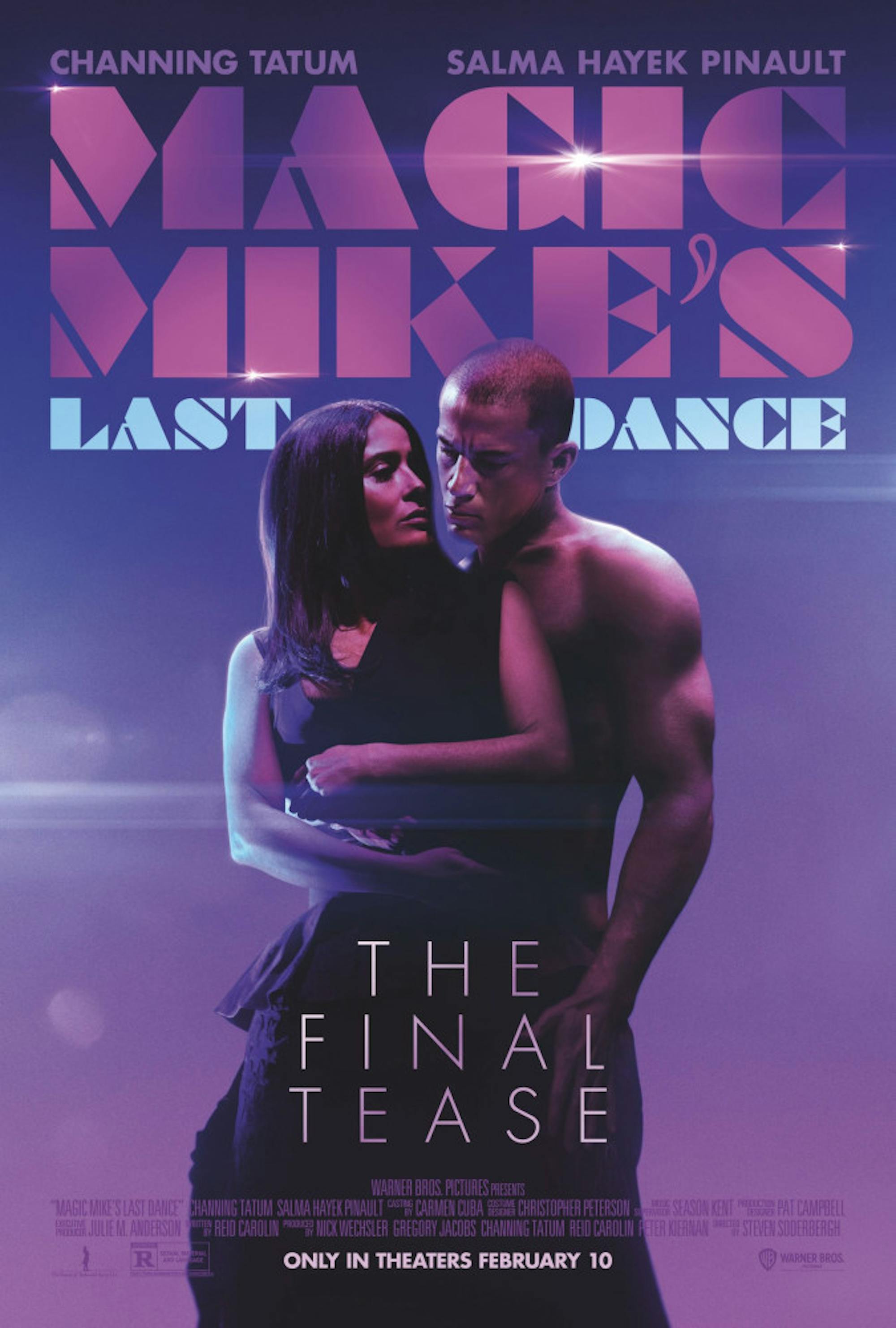

The time has come: “Magic” Mike Lane is hanging up his G-string and packing away his body oils. No longer will he grind and flex — or so he says. In Steven Soderbergh’s latest installment, “Magic Mike’s Last Dance” (2023), Soderbergh follows Mike (Channing Tatum) as he is drawn to the stage for his final striptease. What can I say? The man just can’t seem to keep his hips from gyrating.

“Last Dance” is the third and final chapter in the “Magic Mike” (2012–23) trilogy. Each film in the series has examined the intersections between sex, artistry and, most importantly, getting paid for it. More than 10 years ago, Soderbergh graced audiences with the first installment, “Magic Mike” (2012), which follows Mike and his entourage as they navigate the seedy underbelly of the Florida stripping scene. A few years later, in “Magic Mike XXL” (2015), directed by Gregory Jacobs, Mike has quit stripping and started his own furniture business. Since his business isn’t going that well, he realizes that one final tease could make him a pretty penny. That wouldn’t be the last you see of Mike, though. He takes the stage one last time in “Last Dance,” a story that examines the dynamics between artist and patron and the stickiness when sex is involved.

The story begins with Mike, who has resorted to bartending at fancy charity events after losing his furniture business. At one of these events, he meets Max (Salma Hayek Pinault), an unhappy socialite looking to get her mind off her impending divorce. Learning of Mike’s skills from one of the other socialites, she implores him for one last dance. After a brief interval of bashful refusal, he gives her a lap dance nothing short of mind-blowing — with similarly mind-blowing sex afterward. This experience was so life-changing for Max that she decides to bring him back to London with her in exchange for $60,000, but sex is strictly off the table. Instead, she wants to introduce his glistening muscles to London’s historical theater district in the West End. Together, they contrive a sexed-up adaptation of a stiff period drama, “Isabel Ascendant.”

“This is not a strip show,” Max explains; it’s about giving women “whatever [they want], whenever [they want].”

However, what Max wants is continuously in flux throughout the film. The chemistry between the two is striking at the beginning, but soon the film seems to lose focus of the couple. The bulk of the story surrounds the various obstacles the two must overcome to put on the show. Her constant mood swings and emotional upheavals add the only action between them for much of the story. Compared to Mike’s steady good humor, she provides needed refreshment to these flat scenes. The artist-patron relationship between them could raise interesting questions about the ethics of mixing economic and sexual transactions. Yet, the film seems more concerned with Tatum writhing about on the floor.

The dancing, however, is not to be overlooked. The numbers, choreographed by Alison Faulk and Luke Broadlick, bring the same tenacity from the previous films but with more politeness characteristic of the British environment (meaning they’ll ask nicely before they grind on you). While the dancers move with intelligence and grace, there is a certain savagery lurking underneath, threatening release at any moment. Not only do the dancers access a primal intensity, but the audience does as well. Mike said it best: “Do you want to find out how fast a group of sweet, nurturing moms can make you go running, cowering into a dark corner wishing you were never born? I promise you … it can happen just like that.”

Soderbergh is no stranger to matters of the heart, sex and all the messiness that comes with it. “Last Dance” adopts the same flashy and highly stylized production quality of Soderbergh’s “Ocean’s” trilogy (2001–07). But it undoubtedly has roots in Soderbergh’s earliest, and perhaps most minimalistic of works, “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” (1989).

Coincidentally, the same man who revolutionized the indie film market of the ’90s also made some of the most commercially successful film franchises in Hollywood. Yet, these films share markedly similar themes. “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” follows a woman (Andie MacDowell) who is unhappy in her marriage, until she meets Graham (James Spader), an unassuming young man with a unique fetish. He likes to interview women and ask them about their sexual experiences and fantasies. It is a film centered around women’s relationship with sex and what they do or do not want from it. Just a few decades later, Soderbergh created “Last Dance,” following similar themes of female empowerment and sexual agency (but with more shirtless men).

The flimsy storytelling is supported by the performances of Tatum and Hayek Pinault and the alarmingly enticing set design — which in turn is supported by the film’s $45 million budget. Tatum, who actually was a male stripper in his youth, brings an earnest authenticity to his performance. He is a stripper with a heart of gold, reminiscent of lovable icons like Julia Roberts in “Pretty Woman” (1990). However, his affability perhaps goes too far, removing any complexity from his character. This gives the ferocious but hopelessly romantic Hayek Pinault not much to work with. “Last Dance” is well-funded enough to entertain but falls short of engaging. Much like the tame quality of the dance numbers, it is too tightly choreographed, afraid to take one step out of line.