Have you ever wondered what makes a killer tick? Or what exactly went on behind the yellow caution tape? It's natural; the unthinkable fascinates us. Hollywood knows this, as true crime has become one of the bestselling genres out there. Either created as documentaries or as dramatized representations, true crime lauds its purpose as educational. Whether raising awareness for victims or providing an inside look into the mind of a killer, true crime seems to be relatively harmless. However, when these docudramas gain as much visibility as they do, what happens when the unthinkable becomes thinkable for a certain viewer? Can true crime sensitively deal with real tragedies?

There has been a curious phenomenon of serial killer biopics in recent years. They have raised red flags for many reasons, including the glorification of the killer, exploitation of the victims’ death, indulgence in violence, lack of accuracy and lack of respect for the victims’ families. There is much risk when dealing with real-life gruesome tragedies, calling into question the ethics of creating this type of media. Moreover, producers can’t control the impact the media has on audiences, especially impressionable ones.

Many of these harmful effects arise from casting Hollywood heartthrobs as the killers in question. It raises the question: Is that really necessary? Doing so can blur the line between appreciating the actor’s performance and simply glorifying the killer. More importantly, it overestimates the viewer’s ability to differentiate between their support for the actor or the character.

It’s more than just a theory; scientific studies show this is a common psychological occurrence. In Nurit Tal-Or and Yael Papirman’s paper, “The Fundamental Attribution Error in Attributing Fictional Figures’ Characteristics to the Actors,” they found this struggle prevalent in media-viewing. The fundamental attribution error describes the tendency to think that the behavior of people is influenced by their disposition, not by the situation they’re in. Meaning, an actor is likable because their character is, not because they’re acting.

A similar phenomenon is the halo effect, which allows positive or negative traits to spill over from one area of life to another. A common bias derived from this tendency is the idea that “what is beautiful is also good.” These are all well-documented psychological tendencies that most certainly influence how we consume media and the world around us. It’s relatively harmless when the biases deal with characters in lighthearted shows or movies, but what happens when the media handles much heavier topics? How does the halo effect come into play when you’re dealing with an attractive actor who plays an awful person? If these are ingrained cognitive biases, how can we expect to overcome them when dealing with sensitive subject matter?

This issue is making a comeback with the newly released “Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story” (2022–) on Netflix. It is the second Dahmer biopic to come out in the last five years, setting records as Netflix’s most-watched new series in its debut week. The story follows Dahmer from his pursuit and killing of his 17 victims to his eventual arrest and prosecution. The aim of the show, as professed by creator Ryan Murphy, was to shed light on the individual victims’ lives and stories. Whether it was successful at this is up for debate, as the show seemed to raise as much controversy as it did views.

Murphy lauds the series for its educational purposes, yet his approach does not reflect a commitment to accuracy and respect for the people involved in the tragedy. Many family members of Dahmer’s victims have come out against the series, calling out its inaccuracies. Shirley Hughes, mother of victim Tony Hughes, told the Guardian that “it didn’t happen like that.” She adds, “I don’t see how they can use our names and put stuff out like that out there.” Rita Isbell, the sister of victim Errol Lindsey, added to Insider that she was never contacted about the making of the show: “They didn’t ask me. They just did it.” For a show that claims to honor and praise the victims, the victims and their families clearly do not feel very honored or praised.

Eric Perry, cousin of Lindsey, shared similar sentiments and slammed the show for its lack of sensitivity in a tweet on Sept. 22. “It’s retraumatizing over and over again,” Perry tweeted, “and for what? How many movies/shows/documentaries do we need?” Perry puts it very well: for what? How much does the average American really need to know about this topic? The continuous graphic portrayal of these deaths at the expense of the victims’ families is just beating a dead horse. Murphy would argue that it raises awareness about the victims’ stories, yet only 2% of viewers researched the victims after watching the series.

This brings into question the audience’s role in consuming this media. As stated earlier, cognitive biases like the fundamental attribution error and the halo effect play a large role in how viewers interpret media. These biases are particularly potent in younger, more impressionable age groups. When Murphy was reviving this story for his series, one can wonder if he thought about the kind of effect it would have on younger viewers. Clips from the show are regurgitated on platforms like TikTok, glorifying the series in ways that deviate from its educational intent.

TikTok is a popular platform for discourse among younger generations. So, it is important to consider what kind of conversations will be had concerning real-life tragedies. Unsurprisingly, the series’ “educational” aim didn’t translate on the app. There have been countless videos on TikTok minimizing the severity of the murders, as creators joke about grabbing drinks with Dahmer or dressing up as the serial killer in an effort to appear attractive. Despite Murphy’s intention to highlight victims’ stories, reactions seem to sidestep this and remain impressed by the lead role.

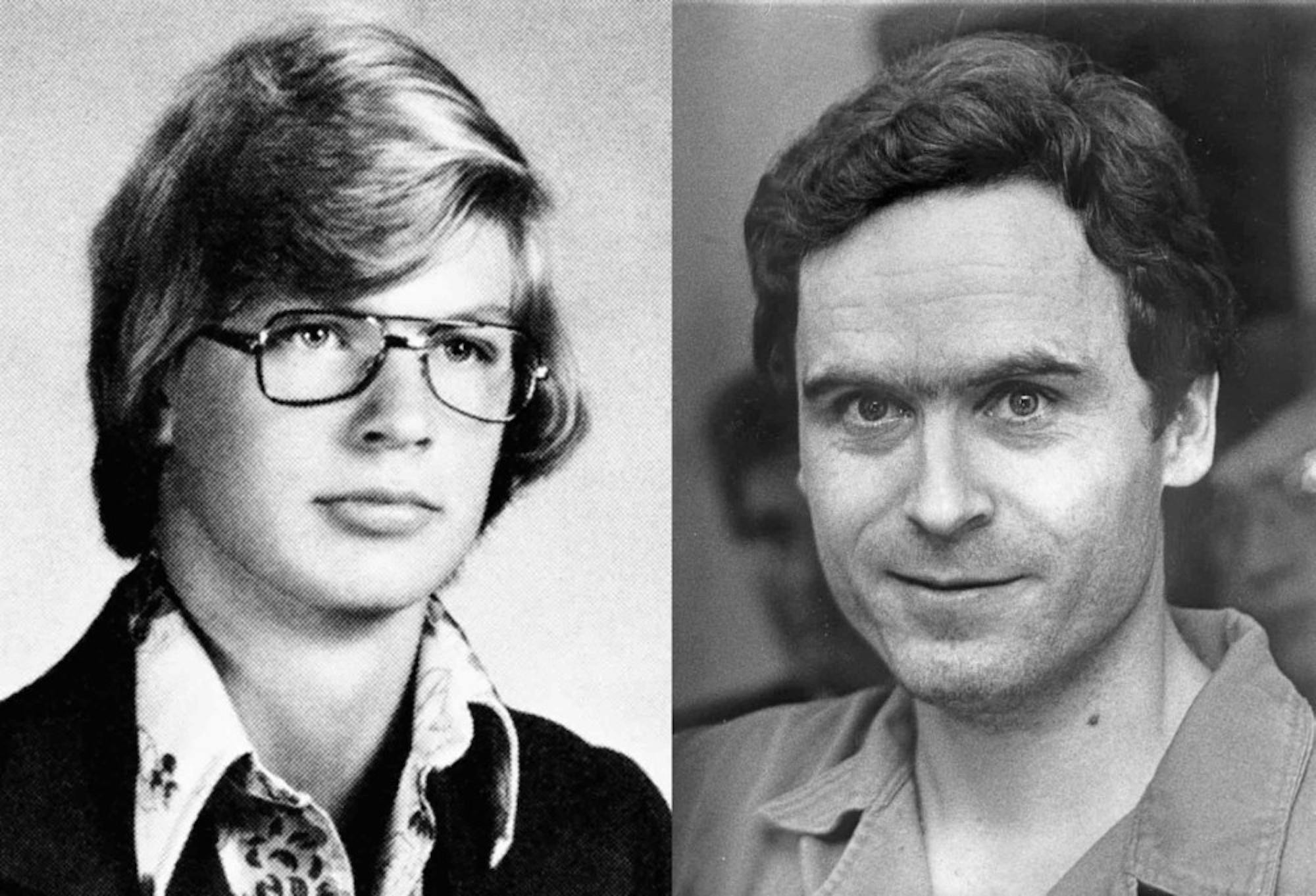

Casting likable and attractive actors in killer roles opens the door to this kind of reaction. This effect is seen in the other few biopics that came out in recent years, including “My Friend Dahmer” (2017) and “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile” (2019). The former follows Dahmer’s origin story, and the latter follows Ted Bundy and his murders. Ross Lynch and Zac Efron play the killers, respectively. Both of these choices were interesting since these are two notable Disney icons. The two boys who characterized many people’s childhoods are now seen killing animals and brutally murdering women. More than tarnishing the view of the actors, it softens the view of the killers. Viewers have already connotated Efron and Lynch with the fond memories, so they can’t fully connect with the evil portrayed on screen.

Sure, attractive castings could be for historically accurate purposes. Ted Bundy, for example, famously used his charm and looks to lure women to their deaths. Controversial artistic choices are not inherently bad, but they must be made for a truly good reason. Efron’s casting is distasteful even if accurate. Seeing likable actors play roles like these does more harm than good, especially since you’re dealing with real stories and individuals. Efron, Lynch and Peters already have a fanbase and following that they’re bringing to these roles, subconsciously training audiences to sympathize with killers over repute them.

Not to mention, most viewers didn’t experience the killers in real time. Studies find that the majority of people watching true crime are under 34. If viewership is primarily younger demographics, most wouldn’t have been around when these killers were active. They missed the real-world impact and presence these people had. These killers end up becoming legends of sorts, their stories distant myths. As the distance between the real event and dramatized representation grows, the role the actor plays won’t hold as much tragic weight as it used to. Thus, it becomes easier for the role to be glorified.

True crime is an undeniable guilty pleasure for many, and perpetually in demand. At its best, it educates the general public and raises visibility for the victims involved. At its worst, and most common, it repackages and sensationalizes the tragedy into exactly what it is — entertainment. As long as these tragedies are increasingly commodified, people will inevitably view them as such. The glorification not only feeds into the serial killer’s desire for fame and recognition but retraumatizes the victims and their families. If docudramas must be made — and it seems as though they will, considering the profitability of true crime — the representation should be as respectful and grounded as possible.