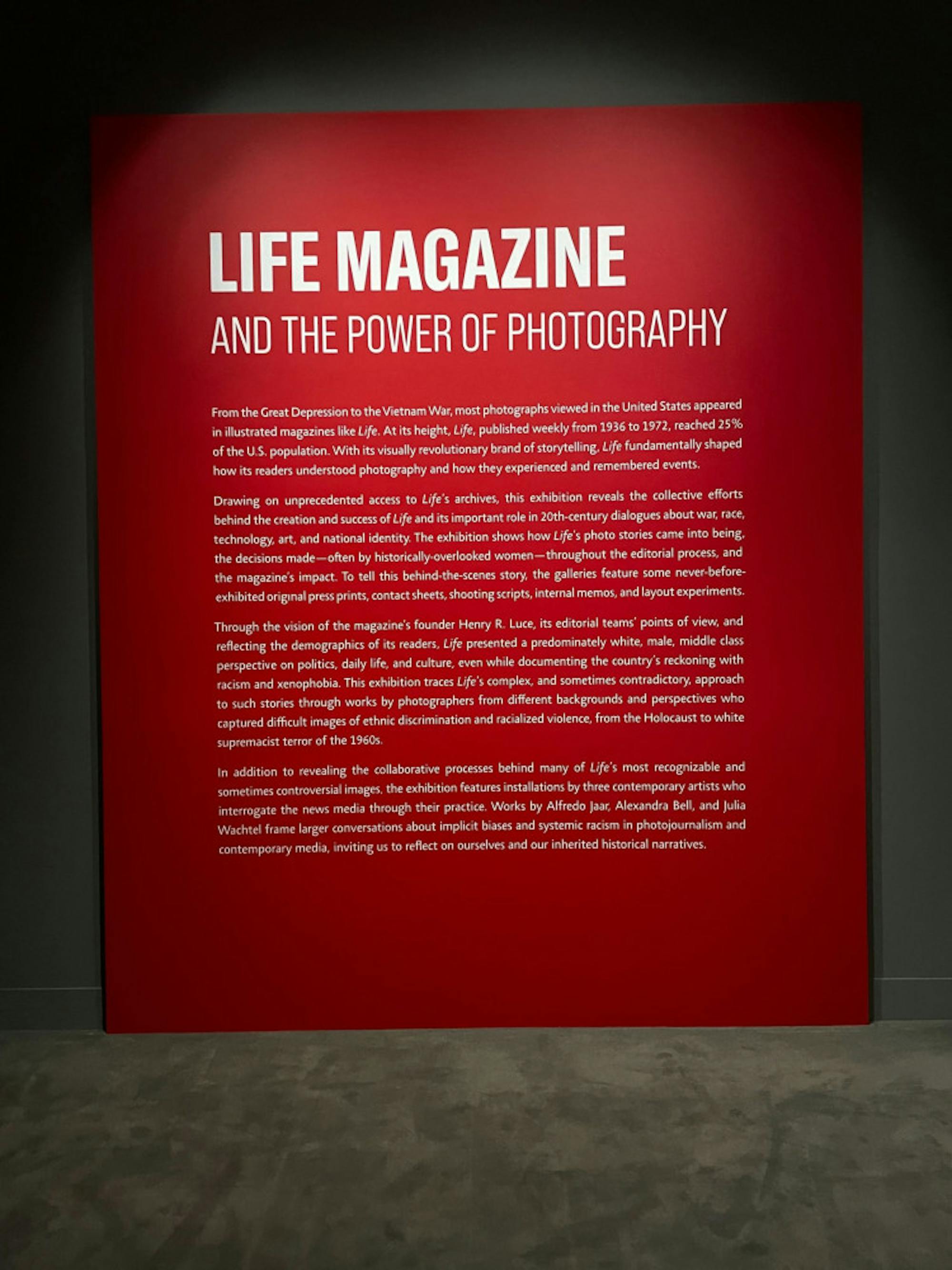

For much of the 20th century, LifeMagazine conquered mass media as the primary visual source for current events. From 1936 to 1972, the magazine presented the public with carefully crafted images that captured real-world social and political narratives. Henry Luce, the publication’s founder, was able to expose readers to a wide variety of images outside of their immediate community, shaping discussions about contemporary issues in the process. As the Museum of Fine Arts puts it in its new exhibit, “with its visually revolutionary brand of storytelling, Life fundamentally shaped how its readers understood photography and how they experienced and remembered events.”

The exhibit, “Life Magazine and the Power of Photography,” documents these crucial photographs, stories and histories. Through its well-crafted presentation of original negatives, contact sheets, vintage photographs and internal communications, viewers are taken on an immersive journey into not only the magazine’s history but America’s as well.

Walking into the exhibition, viewers are invited to sit down beside a vintage coffee table surrounded by suburban wallpaper reminiscent of the 1950s and flip through issues of Life from that era. Unlike most museum exhibitions, in this instance, the MFA is directly inviting viewers to interact with the exhibition’s subject of study. For young audiences not familiar with Life or its general structure, this display provides a fantastic opportunity to connect with and understand the publication’s appeal before continuing.

Subsequent rooms cover the publication’s founding and its early history. Viewers have the opportunity to read Henry Luce’s original telegrams describing the magazine’s purpose and analyze early “dummy” versions and drafts of Life’s first issue. Prints by Margaret Bourke-White, one of Life’s first photographers and its very first female photographer, are displayed, including “Fort Peck Dam, Montana,” the 1936 image that became the magazine’s first cover. Other iconic images on display include J.R. Eyerman’s “Audience watches movie wearing 3-D spectacles” and Yousuf Karsh’s famous portrait of Winston Churchill sitting with his cane and glaring into the camera with his powerful stare.

These photographs are complemented by a variety of text panels surrounding each section of the hall, which provide insight into the photographers and the processes involved in capturing some of the 20th century’s most influential images. Rather than simply presenting recognizable pictures to the viewer, the exhibit makes an effort to educate visitors about the journalistic process — describing how stories were assigned, how agency photographers composed their own shots and how scripts were involved in these visual narratives. Visitors who download the MFA’s mobile app have the opportunity to listen to interviews with Life reporters who share their first-person experiences with the photographs and stories presented.

Apart from simply describing these artifacts, “Life Magazine and the Power of Photography” also explores the magazine’s focus on the deeper, heavier themes that came to define its lasting influence. Photographs by W. Eugene Smith, grouped together, highlight the healthcare challenges faced by Black women in the poverty-stricken South. Images captured by Larry Burrows illustrate America’s harsh timeline of war — especially the Vietnam years and the trauma they inflicted. The visual groupings highlight the importance of these histories beyond the magazine itself and educate visitors about how these major topics were received and documented in American media.

Though it glorifies some of Life’s successes, the exhibit also carefully considers the magazine’s shortcomings too, especially regarding its “predominately white, male, middle-class perspective on politics, daily life, and culture.” In a section featuring images of civil rights protests, the museum makes an effort to highlight some of the inaccuracies promoted by Life, such as the magazine’s failure to describe police as aggressors in images of racially-motivated violence. The exhibit is conscious of the white, suburban bias of Life’s audience and of the people interviewed in stories as well. Presented with a holistic view of the publication, museumgoers are reminded that often, in journalism, key perspectives are excluded from mainstream narratives.

Beyond the magazine’s actual contents, the exhibit features several installations by contemporary artists Alfredo Jaar, Alexandra Bell and Julia Wachtel. Their artwork extends the dialogue presented in “Life Magazine and the Power of Photography” by highlighting contemporary shortcomings in journalism, including its biases and problematic narratives.

“Life Magazine and the Power of Photography” is one of the most interesting and insightful MFA exhibits in recent history. From the photos displayed to the supplementary materials provided, the exhibit tells an exciting narrative about the history of modern America and its relationship with media.

“Life Magazine and the Power of Photography” is open to the public from Oct. 9 through Jan. 16, 2023 at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.