“Hay un ruido que no logro, que nunca he logrado identificar: un ruido que no es humano o es más que humano.” (“There is a noise that I cannot, that I have never been able to identify: a noise that is neither human nor more than human.”)

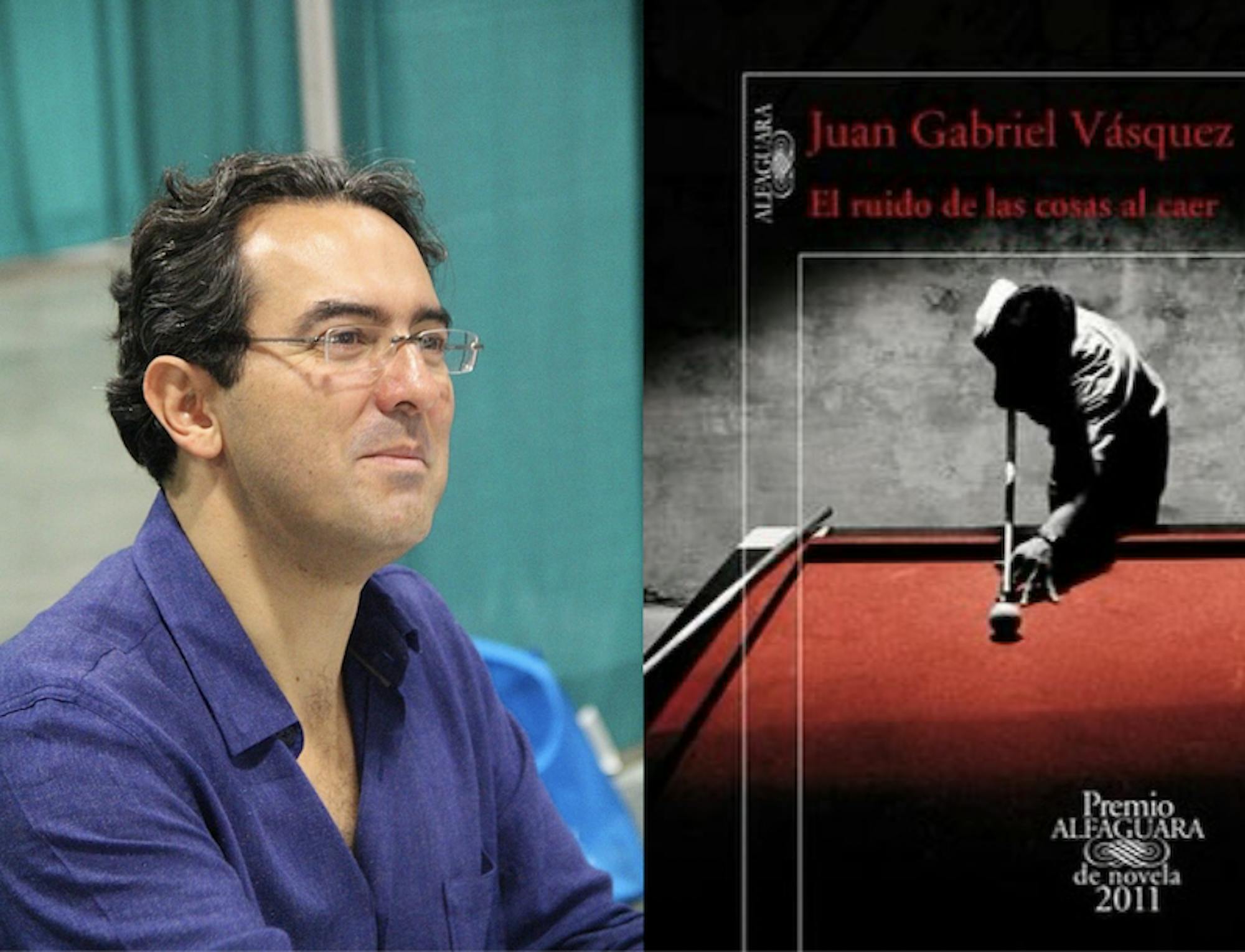

In his most renowned book, Juan Gabriel Vásquez wastes no time to probe the readers’ mind. Like many of his other titles, “The Sound of Things Falling” (2011) takes a very common verb and uses it in a nothing but confusing manner to preface Vásquez’s work. The reader may know the sounds of many things, but what could the sound of things falling be?

Vásquez is a Latin American writer, journalist and translator, from Bogotá, Colombia. Although he has spent most of his professional writing years abroad, his pieces aim to narrate and feature the realities of the Colombian and Latino peoples, just like his predecessors from the “Boom” — a movement in the 1960s and 1970s when Latin American literature became greatly popularized worldwide. Mostly recognized for his contemporary imagery and superb representation of human interactions, Vásquez has earned his place into the Latin American canon, as well as being considered one of the most influential active Latin American writers.

“The Sound of Things Falling” could be deemed as Vásquez’s odeto the city that birthed him: Colombia’s capital, Bogotá. Using Bogotá as an essential character, instead of a setting, this piece presents a short memoir of Antonio Yammara. Antonio, as the narrator, remembers the worst portion of his life by focusing on telling the story of another man, Ricardo Laverde. Antonio meets Ricardo, a mysterious ex-convict and retired pilot, playing pool. Although their relationship revolves fully around playing pool, one day, Antonio helps Ricardo find a tape-player in the city. When they walk out, Ricardo is shot to death, and Antonio catches a bullet in the crossfire.

As Antonio falls deep into depression and experiences PTSD, his daughter is born. He decides he will find out who Ricardo Laverde was and what got him killed. As he probes deeper, he finds the tape Ricardo listened to right before his murder. Finally, Maya, Ricardo's daughter, reaches out to him. Together, they piece together her father’s life, while also uncovering themselves and the impact that living in Bogotá and being Colombians had on them.

The plot of “The Sound of Things Falling” is not intricate. Vásquez was able to create a humane prose — one that mirrors real people — by choosing a simple story and focusing on excelling the manner it is portrayed.

One must first note the use of the setting, Bogotá. The book has a beautiful description of the capital of Colombia, naming and showing to the reader many of the landmarks of the city, like La Candelaria, El Centro, la Casa de Poesía Silva and more. Nonetheless, Bogotá goes further than just being detailed imagery, it becomes an actor in the story. The violence, the fear, the weather and the characteristics of the city, all have influence over the characters and the actions. One of the characters even specifies that all raised in Bogotá during the ‘80s had some sort of connection — a mark — created by all the events they had to live through: the terrorism from the drug cartels, the corruption of the governments the murders of social leaders. Turning on the TV only showed more terrible news. By using Bogotá as an actor, Vásquez vividly depicts a reality of the Columbian people: deeply engraved in trauma created by the atrocious conditions and events of their homes.

Vásquez’s depiction of trauma in this piece is sublime. Not only the trauma mentioned above, but also through exploring the feelings and thoughts of the narrator. Similar to accounts of wounded-in-battle soldiers, the reader gets a peek of what an injury of that magnitude can cause to a human being. Additionally, Vásquez breaks a mental-illness stigma for Latino men by openly talking about PTSD and demonstrating how it sends Antonio into a downward spiral — developing fear towards his own home, madness, sexual impotence and more.

The beauty of how “The Sound of Things Falling” portrays trauma also lies in the lightness the narrator keeps while still depicting all these atrocious events. At its core, the narrator represents what life is in South America: the ability to take traumatic events lightly to keep going. To perform the latter, the reader follows a very conversationalist narrator, which is a contemporary trait. Vásquez mimics real life conversations by using simple language, slang and curse words. He can almost seamlessly change perspectives, delve into fully different accounts and jump between storylines. One more aspect of Vásquez’s light narration worth noting is his use of irony and comedy, which aids the “swallowing” of strong events. An example can be seen after Antonio’s wife gives birth, and she exclaims, “I think the glove really did belong to O.J. Simpson.”

The contemporary-style narrator from Vásquez breaks the long-standing notion that Colombia’s, and Latin America’s, suffering and problems are a matter of the past. The world can only remember Pablo Escobar, but now that he’s dead, what about all those who come after? Although the country has changed for the better, what about the generations that had to live through all that pain and suffering? That is exactly what the book tries to hint at. By using a contemporary setting and style as well as a superb depiction of trauma, Vásquez reaffirms that the troubles of the Colombian people are not gone; they linger far beyond, but the world has forgotten about them.

So, what is the sound of things falling?

In his search for the story of Ricardo Laverde, Antonio finds the tape he listened to right before he was murdered. The tape was the ‘black-box’ recording of the plane crash that Ricardo’s wife died on. As he listens to it, he details what he hears: a “more than human sound … a sound that never finished.” Antonio, and thus Vásquez, insinuate that the sound of things falling is that never ending desire for more information, for the ultimate truth; that’s why he never stops searching for who Ricardo Laverde was. When Antonio listens to the tape, he opens Pandora’s box; he becomes submerged in the infinite search of the truth, in the infinite sound of things falling. And that’s what Vásquez does with this book, he searches for the truth: the truth of the Colombian people, the truth of what Bogotá did to him. That intimate passageway between the story and its author is what has given his work much reputation, even landing him the prestigious Spanish Literature award “El Premio Alfaguara de Novela” (The Alfaguara Novel Prize).

Why, when “The Sound of Things Falling” has won this award as well as the PEN and Impac Dublin awards, isn’t it more widely known? If it was extensively praised in The New York Times, why isn’t it sold in more bookstores?

It seems as if the public has forgotten about the search for the truth — about the sound of things falling.