At the start of each school year, students adjust to new classes, living situations, social dynamics and more. For the past three years, the “more” part of this sentence has included a spate of guidelines designed to protect the Tufts community from COVID-19.

During the 2020–21 school year, students were severely limited in where they could spend time, participated in surveillance testing and were required to wear masks everywhere they went on campus, aside from in their own bedrooms. When students were infected with COVID-19, both they and their close contacts moved into quarantine or isolation housing. The 2021–22 year brought with it a near-complete return to in-person classes — and in-person social life — but continued the indoor mask mandate with less intense surveillance testing and isolation programs.

Now, masks are not officially required anywhere on the Medford/Somerville campus, and there is no surveillance testing. Instead, voluntary testing is available to members of the Tufts community who are exhibiting COVID-19 symptoms. Students who test positive for COVID-19 are not asked about their close contacts, and those who live on campus remain in their dorm rooms, even when they have roommates. While less far-reaching than the transition between the spring and fall 2021 semesters, the changes this year have had serious impacts.

What happens when you test positive?

Those most affected by Tufts’ COVID-19 policies are, of course, students who test positive for the illness. Sophomore Kaya Gorsline went to get tested after hearing that a friend had COVID-19, and she received an email a few hours later telling her that she had also tested positive and that she should self-isolate. Rapid tests are available to anyone with an active Tufts ID who was in close contact with someone with COVID-19 or who is experiencing symptoms; students also reported being offered PCR tests. When Gorsline tested positive, the university did not provide any official instructions on contact tracing for students.

“The university and local public health authorities are not conducting contact tracing for COVID-19. If you test positive for COVID-19, you are responsible for notifying close contacts and letting your professors know that you are unable to attend class. Students do receive messaging with instructions if they test positive or report a positive test to COVID testing,” Michael Jordan, Tufts infection control health director, wrote in an email to the Daily.

Gorsline, who described herself as conscientious about public health, took it on herself to reach out to close contacts.

“It was all me reaching out. Tufts didn’t tell me to contact anyone. They didn't tell me when my friends who I’d seen had gotten COVID,” Gorsline said. “Basically it was just me; I texted everyone I’d seen in the past three days, and was like, ‘Hey, I have COVID, you should probably get tested.’”

Once she entered quarantine, Gorsline was faced with the challenge of sharing a living space with people who weren’t infected. Her roommate had recently had COVID-19 and wasn’t concerned about catching it, but Gorsline worried about spreading COVID-19 through shared bathrooms.

Although all of the bathrooms in Harleston Hall, where she lives, are single bathrooms, she was worried about leaving COVID-19 particles behind after using the space with her mask off. Tufts officially declined to provide specific bathrooms for sick students, but Gorsline’s RA quietly “bent the rules” and designated two bathrooms — one of which was handicap accessible — for COVID-19-positive students.

An-lin Sloan, another sophomore who lives in Harleston and had COVID-19 in September, had a trickier time navigating infection. Her roommate had not recently been sick and was worried about catching it; rather than continuing to share the space, Sloan’s roommate decided to stay with a friend for Sloan’s 11-day quarantine, only stopping by her dorm to pick up toiletries and other supplies while fully masked.

Medical Director of Health Service Marie Caggiano reiterated to the Daily by email that temporary housing units are reserved for high-risk students and that for other students living with roommates who have COVID-19, both roommates should wear well-fitting masks.

“Students living in campus housing who are at high risk for COVID––for example, those who are immunocompromised or have been approved for a medical accommodation to the vaccine policy––may be housed in temporary housing until their COVID positive roommate completes their isolation and tests negative,” Caggiano wrote.

For Sloan’s roommate, masks didn’t provide enough comfort.

“She … [wanted] to sleep elsewhere just to be safer, although I would have been fully okay with wearing a mask 24/7 while she was in the room [and] while I was sleeping if she wanted to, but she decided to leave,” Sloan said.

Sloan and Gorsline both said they wished Tufts had a more comprehensive policy in place to avoid this sort of spread. Another challenge that each of them faced while in quarantine was keeping up with their classes.

“I found that my classes weren’t very accommodating to virtual students. I had a few big lecture classes where I could go virtually, but a lot of my classes are small seminars, so I had to basically just stay on top of the readings and do the discussion posts and just kind of hope I wasn't missing too much of class,” Gorsline said.

Sloan agreed, saying that it has taken longer for her to recover academically from getting sick than it has for her to recover physically, even though her professors did their best to be accommodating and included information on COVID-19 policies in their syllabi.

Professors have been allowed to accommodate students who are out however they see fit, although the university has given guidance on how to make that decision. Holly Taylor, a professor in the psychology and mechanical engineering departments, is offering a Zoom option for her lecture-based course but decided not to for her smaller, discussion-based seminar about games and psychology.

“I found with my seminar that it really doesn’t work to use Zoom. It's all about discussion, so going from small groups to full classroom discussion, and trying to include a student on Zoom for that class, when I tried it last semester, really doesn't work,” she said. “My approach is that I’m requiring communication from the students to let me know what’s happening, and then I’m happy to work with people to make sure that they’re not getting behind.”

Other professors interviewed for this story had a similar range of policies, although all were clear in that they wanted students who were out because of COVID-19 to be able to stay on track as much as possible. Nevertheless, it wasn’t easy for Sloan or Gorsline to feel connected with the work for their smaller classes.

As they prepared to end their isolation, both Gorsline and Sloan faced one more challenge: They wanted to leave their isolation as soon as they began testing negative on rapid antigen tests, but Tufts guidance would only let them ‘test out’ on days five, seven and 10 of isolation.

“Even though I tested negative on a home rapid they wouldn’t let me get tested officially to get released early,” Gorsline wrote in an email to the Daily.

Masks off — sometimes

In addition to changes to what happens when a student tests positive for COVID-19, Tufts’ policies no longer require masks on Tufts’ undergraduate campus (and in most spaces on its graduate campuses), which has had effects from the classroom to extracurriculars. According to the university’s official policy, masks must be optional: No one is allowed to require them, nor is anyone allowed to prohibit wearing them. Some professors have found that not wearing a mask — which the vast majority of students have opted for — has changed how students are interacting with each other in class.

Taylor teaches engaging classes that require participation in both activities and in discussions.

“I wonder whether the mask mandates also put up sort of a barrier to social interactions,” she said. “I do ask students if they’re not feeling well to wear a mask, and any student who would like to wear a mask obviously can. But I think that social interaction flows slightly better without. So I am observing this semester that the level of interaction among students and with me is getting back to what I would call the ‘old normal,’ and I would say it was not there last year much.”

In other classes, fewer people wearing masks is actually making the material easier to teach. Professor Barbara Wallace Grossman of the Department of Theatre, Dance, and Performance Studies teaches two classes, one called “Holocaust Stage & Screen” and the other called “Voice and Speech: The Art of Confidence Expression.” In the Holocaust class, not wearing a mask has made teaching a more pleasant experience, she said.

“Last year, when I taught the Holocaust course, I taught it once a week for three hours, and three hours dealing with that material in masks was really, really challenging,” Grossman said. “This semester is twice a week, and mask wearing is optional, and it just feels like a lot lighter way to approach an in-depth dive into such dark material. It’s nice to not have to wear the mask.”

For other professors, though, the end of the mask mandate created new questions about how they would teach their courses. History professor Virginia Drachman thought about how being in the classroom would interact with her own health risks. Drachman, who is teaching two small classes this semester, is back to teaching in person for the first time since the spring 2020 semester. She explained that she missed being with students in person and being in the classroom.

“I'm totally in that age group that’s vulnerable. I have different health concerns, as does my husband. And so I had to think about, ‘How would I feel comfortable, and what would make it possible for me to do this in the classroom?’ And I basically decided that I needed to create an environment that was as safe as possible, so the first day of each of my classes, I talked about this,” Drachman said.

“I explained that I would be wearing a mask for the whole class and that I needed the class to do the same, and I also said that I totally understood that this is annoying, it’s uncomfortable, no one likes it but that in order for me to feel comfortable and safe to be in the classroom, this is what we have to do. I also said that I totally understood if anybody chose not to take the class for this reason.”

Despite some initial worries about how students would respond, Drachman has been overwhelmed by students’ receptiveness to her request. No one dropped either of her classes because of this, and students have respectfully worn masks in both classes.

Back in the theater department, Grossman’s voice class, which focuses on physically developing the voice, communications skills, public speaking and mindfulness, is also being offered in-person this fall for the first time since spring of 2020.

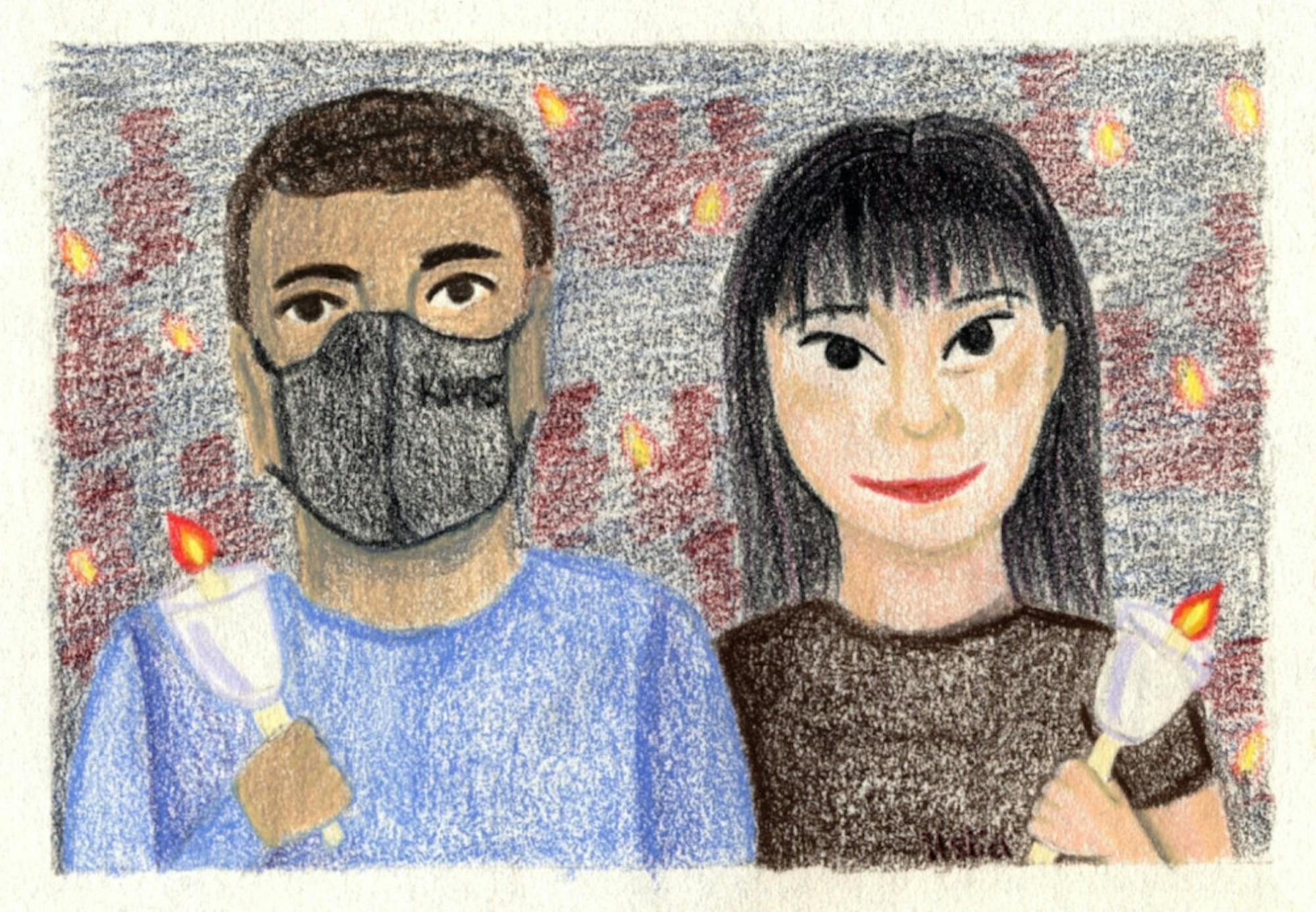

“I felt very strongly, even last fall when I came back to in-person teaching for my other class, that for voice, it was really important for faces to be unmasked. [With] voice and speech, as you would imagine, so much focus is on how you’re shaping your words, what your facial expression is, and also with a mask on, it muffles the audibility of it. So I just thought, ‘Oh, my goodness! Imagine teaching voice when people are like this,’” she said, putting a KN-95 over her face. “Trying to hear them and see their mouths move: not happening.”

The difficulties of wearing a mask in a voice class are similar to those faced more broadly in the performing arts at Tufts. Grossman directed Spring Awakening last semester, and students were required to wear masks for the whole performance, which included moments of physical intimacy.

“Normally in theater, what do you rely on? You rely on facial expressiveness,” she said. “And [with masks] you can't. You have to make sure [to have] eye energy, gestures.” For the intimate scenes, actors worked with an intimacy choreographer to figure out how to use their bodies to show intimacy while still wearing their masks.

The Beelzebubs, one of Tufts’ a cappella groups, had a similar experience. Its members are used to bringing excitement to their performances through their faces.

“Our brand is bringing energy and super positive vibes, and a lot of that is face expression and how we emote,” sophomore Varun Sasisekharan, a member of the Bubs, said. “That was a part of our performances that was fully taken away because half our faces were covered.”

This year, the Bubs and other a cappella groups are back to a performance schedule that’s close to what it was like before COVID-19 affected campus and are relieved to not have to wear masks, especially because of the impact they’ve had on audiences’ abilities to hear them during shows. Other performing arts groups, including Tufts’ student-run musical and play groups, are also excited to be performing without masks this semester.

While precautions remain in place and there is still some nervousness around COVID-19 on campus, many students are breathing a sigh of relief.

As senior Sid Iyer put it, “Just a greater proportion of people are a little more comfortable, just like socially and going out and about now this year. … It’s a little more, I have freedom to be a little more outgoing and stuff, which I think is nice.”