Faint bubbles twist their way to the top of an inconspicuous green container about the size of a hand. Among the miscellaneous bottles and boxes on the countertop, you wouldn’t give the box — called an SDS-PAGE — a second glance, and you certainly wouldn’t guess what it was up to. In reality, this device is not a more boring version of a lava lamp, but a part of a larger effort at Tufts and beyond to redefine the food industry.

The small green container, nestled in a corner of Tufts’ antiquated Science and Technology Center, is one of many tools researchers are using as they work day and night to change the game of growing edible meat in a lab through a process known as cellular agriculture. If they’re successful, cellular agriculture could have huge implications for climate change, food safety, animal welfare and more.

“Think of it as using cells to make the food of the future,” says David Kaplan, who is the principal investigator of the lab and the chair of the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Tufts. It’s a future many, including the U.S. Department of Agriculture, are excited about; the USDA in October awarded a grant of $10 million over five years to the Kaplan Lab in conjunction with colleagues at Virginia Tech and four other institutions.

Kaplan looks to the promise of cellular agriculture with hope and a healthy amount of skepticism. The idea of a large-scale industry around cultivated meat has been touted as the future for years, but Kaplan and many other scientists say that the logistics and practicality of such a promise are far more complex than many companies make them out to be.

Though the field has seen successes in small-scale laboratory environments, the process of growing meat in a lab is monumentally expensive. Before cultivated meat can be on everyone’s kitchen tables, a whole industry and the infrastructure that goes with it must be developed, which includes the construction of large-scale bioreactors that grow the cells.

To combat these problems, researchers at the Kaplan Lab are looking to rethink and improve the bioengineering process of creating meat in a lab. They also hope to make the final product more like what we expect from taking a bite of a steak or any cut of meat; right now, the industry has struggled to mimic the food in its entirety. It’s one thing to generate a bunch of meat cells — it’s another to have that product resemble the structure and texture of traditional meat.

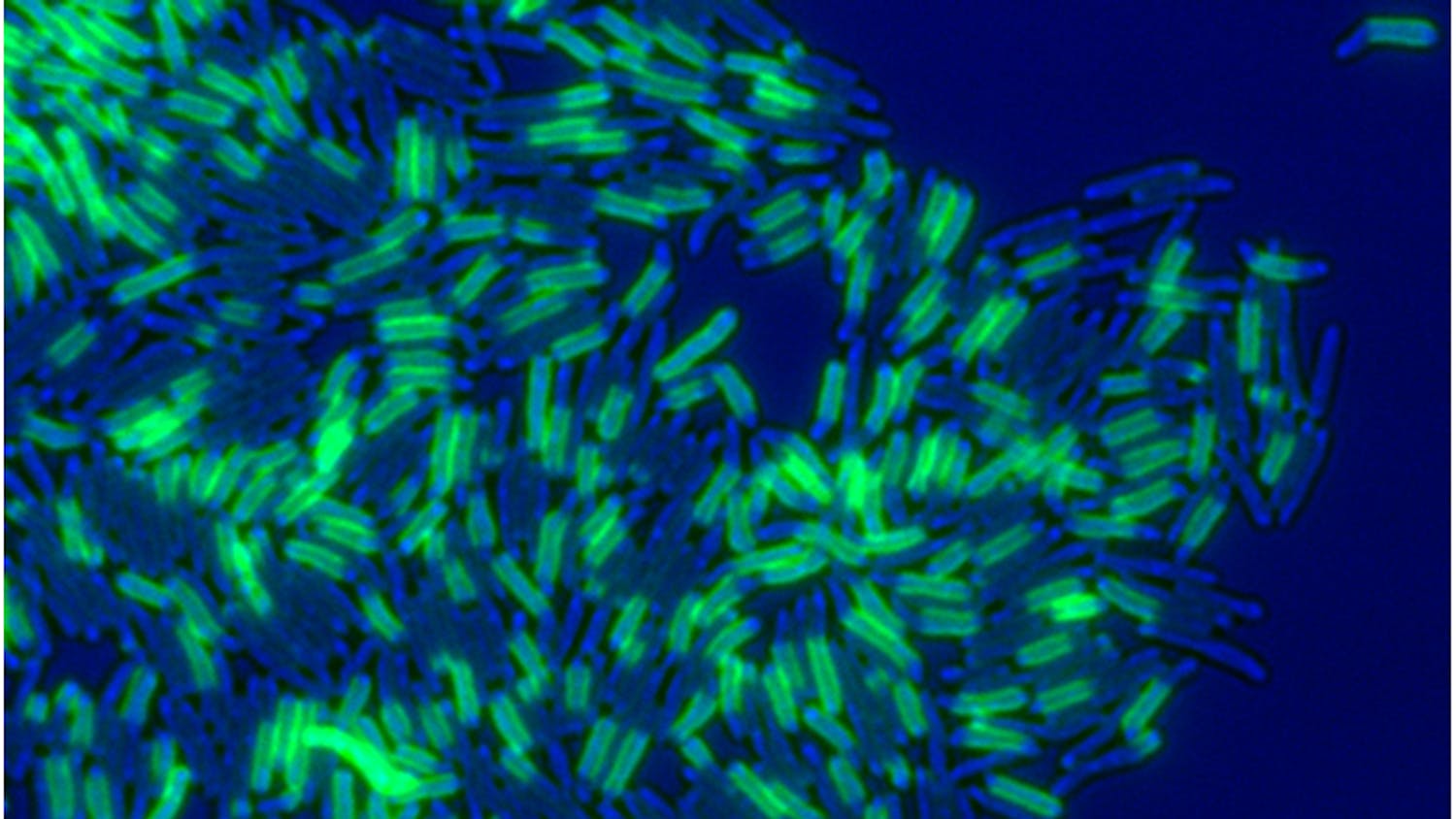

The process of lab-grown meat starts with taking a biopsy of muscle tissue from an animal in a quick procedure that doesn’t harm them. Once those cells are plated on a lab petri dish, they grow from a small bundle of cells into a mass of billions. Eventually, they can develop into something that resembles a small slab of ground beef. To create different types of meat, the researchers use scaffolding, which are structures made of a biomaterial that guides cell growth. This allows the researchers to create meat with the desired form, texture and taste. The scaffolding could be created in several different ways, from 3D printing it to making it in a traditional cast and mold.

“It's almost like being a sculptor,” Kaplan said. “You decide, ‘I need to have something that looks like this, and I use the right tools to make it.’”

This technology isn’t some far-fetched reality. The first example of cultivated meat came out of the Netherlands in 2013 in the form of a $330,000 hamburger which two food critics ate at a news conference. They both agreed it was close to meat but with differences in juiciness, texture and taste. More recently, the world’s first cultivated meat product hit the market in 2020 in the form of chicken served at a restaurant in Singapore.

Around the globe and within the United States, many cultivated meat startups have been founded with the promise that lab-grown meat will lure climate-conscious consumers, much like plant-based meats did with products such as the Impossible Burger in recent years. These promises, in turn, have fueled huge private investments. Upside Foods, a company based in San Francisco, just opened a scaled-up production plant with the capacity of producing 50,000 pounds a year of cultivated meat, seemingly bringing that promise closer to reality.

But there is a key difference between cultivated and plant-based meats: the high costs. Some stakeholders, like startups looking for investments, say costs will come down as production becomes larger scale and the infrastructure is developed, while others say cultivated meat will never be economically feasible. Prices have certainly dropped since that first $330,000 burger — a cultivated meat burger today costs about $9.80. But Kaplan said that the answer is unclear.

“I don’t think any of the projections are really accurate, because no one knows,” Kaplan said. “There’s no data, right? So that’s our goal is to fill that gap.”

Andrew Stout, a Ph.D. student in the lab, agreed that at the moment, it’s unclear how costs will change in the coming years.

“There’s been a lot of hype — and potentially unrealistic hype — about the timeframe that these sort of products might reach the market,” Stout said.

So while cultivated meat may not reach the low target costs companies claim they will within five to 10 years, it’s still possible that scientific advancement in the next 20 or 30 years could bring consumers closer to purchasing the meats at an affordable price in the store.

Despite the uncertainty, researchers are pushing forward because the intense threats of climate change and population growth demand innovative solutions.

“I get questions like, ‘Well, do you think this is going to work?’” Kaplan said. “And I said, there’s no choice, it has to work because if you look at the projections of the population going forward … there’s no way you can feed the planet the way we do it now, so we need alternative ways to generate protein-rich foods.”

Cultivated meat isn’t the only answer to reworking our food production system to feed a population of unprecedented size, but it could be an important one. There are a lot of different possibilities for meats that could eventually reside in grocery aisles; on top of beef, Kaplan’s lab is working to grow cell-cultivated fish, pork, chicken and even insect meat.

Along with providing a valuable source of nutrition for the growing population, cultivated meat could have profound impacts on the environment, food safety, food security and animal welfare. The meat industry uses huge amounts of land, water and energy, so many hope cultivated meat could be a less wasteful alternative. Still, the impact isn’t entirely clear because the process of growing meat in a lab still requires inputs like water and energy.

“The projections seem to suggest lower energy, lower water, lower land use,” Kaplan said. “But how much is not clear yet.”

What we do know is that our current means of meat production have significant environmental costs associated with them. Almost 40% of land across the globe is used for agricultural purposes, a significant portion of which acts as pasture for grazing cattle. Though land will be needed for bioreactors in the production of cultivated meat, it will certainly be much less than that needed to raise millions of cows.

While sustainability is often used in explaining the value of cultivated meat, Kaplan said the impact on food safety is underappreciated. Society could avoid the regular safety recalls of infected meat products and limit concerns over antibiotic resistance by growing meat in a closed environment without the need for antibiotics.

Kaplan and his team hope to develop the solid science that the field of cultivated meat needs to cut through the hype.

“There’s been so much investment in startups to produce these foods, that there’s a gap between what academic fundamental science has demonstrated versus what companies are promising,” Kaplan said. “We’re trying to fill that gap.”

To accomplish this goal, Tufts will collaborate with Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, the University of California, Davis, MIT and the University of Massachusetts Boston in their research funded by the USDA grant — each coming at the problem from a different angle.

Ph.D. students working in the Kaplan Lab emphasized the importance of this joint collegiate effort, especially in a field that is dominated by private investment and companies that keep their research findings tightly sealed.

“I think it was very exciting to get the grant,” Jake Marko, a first-year Ph.D. student, said. “But I think a bit of the flip side is that there’s just a lot of private funding right now. And this is one of very few public funding options for cultivated meat. So I’m very optimistic that there’ll be a lot more of those in the future.”

The funding from the grant will go toward establishing the National Institute for Cellular Agriculture at Tufts, which will also include other investigators involved with the project.

“Tufts will become a location, along with our partner institutions, where anybody can come in for good quality scientific information about the field,” Kaplan said.

Kaplan explained that the institute will be a resource to anyone looking to learn more about cultivated meat from biotech companies to farms to politicians.

“They would know that this center would be a place where information is available, where we can help them with the tools or the education needs or whatever it is so that they get informed quality advice,” Kaplan said.

Both Kaplan and the Ph.D. students emphasized they were open to talking with students or anyone interested in learning more about the lab or the field. There’s a lot to learn and a lot more research to be done.

It’s not clear when cultivated meat will be easily available on the shelves, but one strategy to bring down costs and bring us closer to that day is to combine the new technology with already familiar and successful plant-based products. By combining cell-based products with the cheaper plant-based products that are already so prevalent, companies may be able to find a compromise between the similarity of their products to meat and cost.

“I think that there is definitely a possibility that it’s never economically feasible,” Stout said. “Adapting to that potential has been the thinking of cells as an ingredient, rather than necessarily a full food product.”

Another element of uncertainty comes in the form of infrastructure and scale-up. Right now, cultivated meat is generally produced on a very small scale in laboratory settings. However, many envision a future in which the industry feeds the nation.

“If it were to be really large-scale, creating the infrastructure to allow that to happen would also be a big challenge,” second-year Ph.D. student in the Kaplan Lab Sophie Letcher said. “But that’s not something that we really work on that much right now. Because we’re pretty small-scale just on the academic research side.”

How that industry is set up can also have significant impacts on cost. Marko explained how distribution costs could vary depending on the number and size of bioreactors across the United States where cultivated meat would be grown. He said that if we want to keep those distribution costs low, we’ll need to be intentional and organized about how we develop the infrastructure.

Evidently, there is still a lot to figure out before cultivated meat is widely available, which is why research like that of Kaplan and his colleagues is so critical. Despite the challenges and the questions of feasibility, the potential impact of cultivated meat keeps it a relevant research focus and prevalent topic of debate.

“Research never is linear,” Kaplan said. “Two steps forward, three steps back, three steps forward, one step back. We learn every day. But we have enough momentum and positive output so far that we’re all very, very excited.”