Sterile, green text slowly crawls across a black screen reading, “5 billion people will die from a deadly virus in 1997 … The survivors will abandon the surface of the planet … Once again the animals will rule the world.” A brief line of text attributing the quote to a “clinically diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic” appears and disappears. Finally, the sounds of the arrangement “Suite Punta del Este” (1982) by Ástor Piazzolla cut through the eerie silence. The moment is unexpected, gripping, a bit strange and oddly alluring — a perfect illustration of what’s to come.

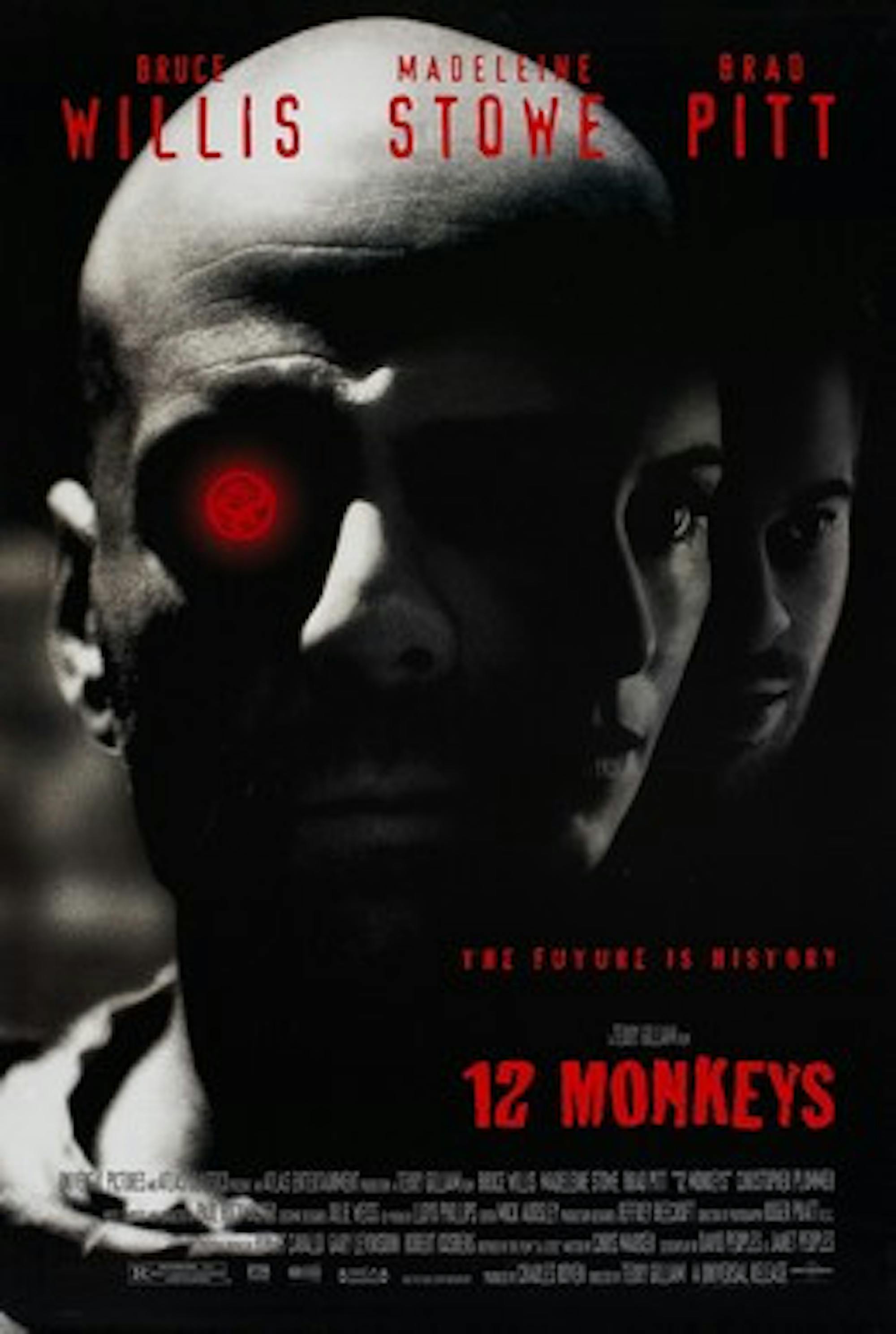

The works of Terry Gilliam are fantastic quilts of creative madness. Though not a stranger to controversy, Gilliam’s works — from the Hunter S. Thompson adaptation, “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” (1998) to the Orwellian satire, “Brazil” (1985) — are stuffed to the point of bursting with details, brilliant costuming, challenging cinematography and a dreamlike aesthetic that is as polarizing as it is hypnotic. An oft-overlooked high point, though, came in 1995 when he released his neo-noir, sci-fi thriller, “12 Monkeys.”

Inspired by the 1962 French sci-fi short film, “La Jetée,”“12 Monkeys” (1995) chronicles James Cole’s (Bruce Willis) ill-fated trip back in time to stop a pandemic from wiping out humanity. Though this premise may draw sharp inhales from many, the film is less about the horrors of a pandemic and more about societal unrest, inequity of power hierarchies and the inherent absurdity of the modern world, as well as beauty, culture and small pleasures as seen through Cole’s eyes. Given Willis’ recent retirement, it feels prudent to mention that he perfectly acts as both audience surrogate and tragic pawn in the schemes of the leaders of the future who send him back in time, again and again, fraying his sanity each and every time. Willis executes Cole’s slow descent into madness as a devolution from a hardened criminal to a confused child with the subtlety and respect that the role demands, giving a performance that deserved far more award nominations than he was allowed.

On the matter of awards, though, Brad Pitt’s nearly unrecognizable turn as Jeffery Goines, the unstable leader of the mysterious “Army of the Twelve Monkeys,” earned him his 1995 Oscar Nomination for good reason.Pitt nails the manic, almost cartoonish energy in a way that plays perfectly against Cole as he is initially losing his mind, and later, Pitt manages to feign sanity exceptionally after Cole has fully lost it. Meanwhile, Madeleine Stowe’s character, psychologist Kathryn Railly, is tinged with a sympathetic vulnerability that makes her own inevitable submission to madness all the more tragic. Even at her character’s lowest point, Stowe infuses a sense of warmth into her performance that makes the character so real she might leap off the screen at any moment.

One can easily tell that Gilliam is pushing his actors to their limits, as he seems to be pushing the boundaries of the world itself. Cole’s future home is a patchwork of tubes, hoses and metal, fused together in a dour bunker miles below the disease-ridden surface of post-apocalyptic Philadelphia. In the past, meanwhile, Gilliam distorts the present day by allowing for high exposure, creating a dreamlike effect as though one is walking through a fog. The visual places us in a dream state along with the disoriented Cole, who staggers through the past, slowly forgetting his mission. Gilliam’s imagination oozes through every frame. His obvious love for cinema is palpable in his various allusions to Hitchcock — from Dr. Railly’s change to a blond hairdo as a disguise to an actual screening of “Vertigo” (1958) in the film’s climax — which act as a support to the film’s intricate plotting and fantastic performances.

“12 Monkeys” is at times grim, hopeful, dark and comedic, but it is always a powerful experience that deserves to be appreciated. While not Gilliam’s most celebrated work, the film is an overlooked classic in modern discussions of science fiction and noir cinema at their finest. Its highbrow subject matter, refusal to hold the hands of the audience and exceptional direction from one of cinema’s true auteurs make it an unmissable and unforgettable film in this — or any — time.