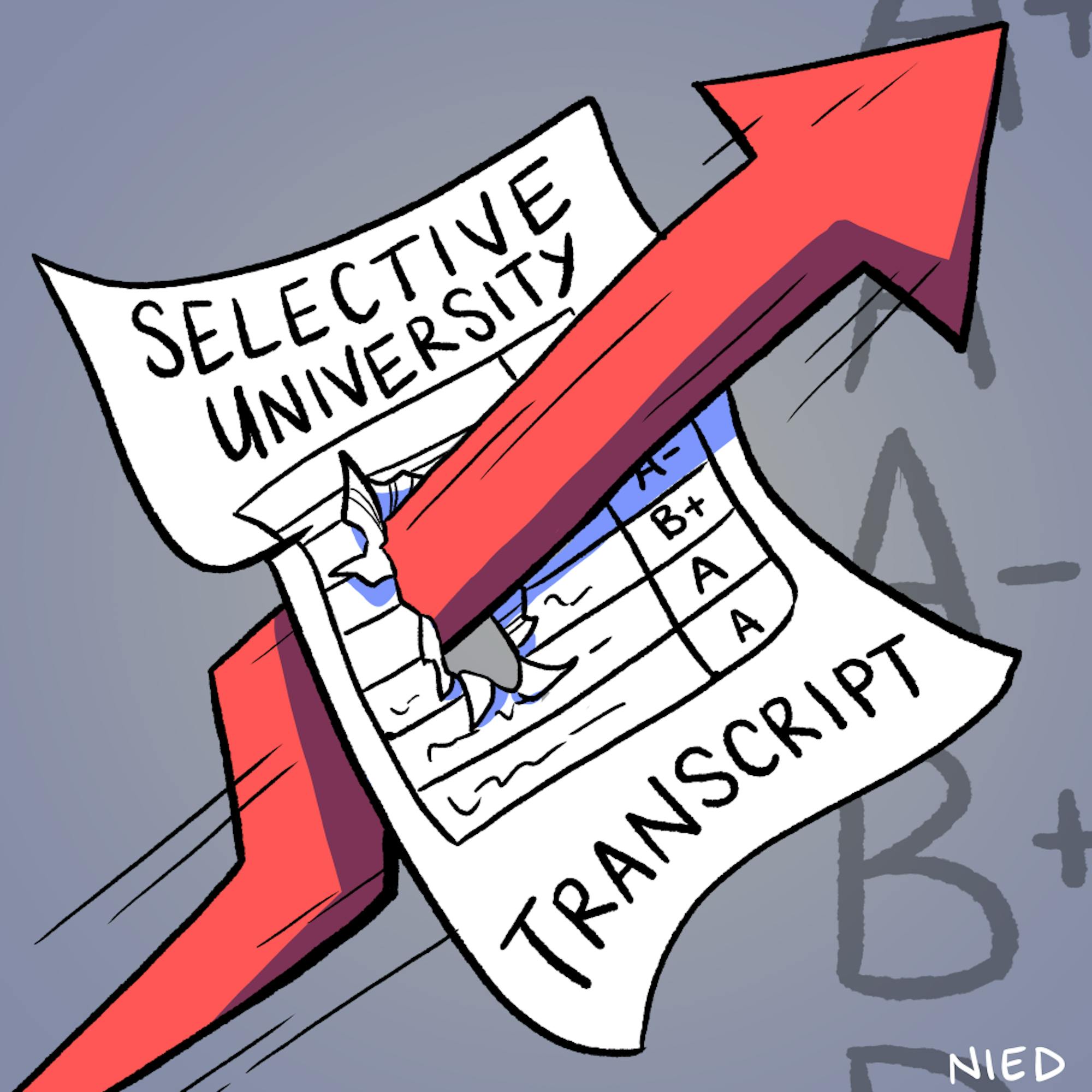

If the letters ‘ABC’ send a chill down your spine, perhaps you’re a Tufts student and currently in the middle of midterm season. As Tufts becomes an increasingly competitive institution, here we will take a look at grades at Tufts in the national context of grade inflation.

Looking broadly, a 2010 study from the Teachers College Record found that grade point averages of public and private colleges rose significantly during the height of the Vietnam War and have been rising steadily from the 1980s onwards. Tufts was not featured in the data, though a 2008 article published in the Daily revealed a rise in average GPA from 3.26 in the 1997–98 academic year to 3.39 in 2007–08 for the School of Arts and Sciences.The Office of the Registrar’s policy on sharing information about average GPA prevented them from being able to provide more recent information to the Daily.

Deans of Academic Affairs Samuel Thomas and Heather Nathans, both of whom are also professors, shared that Tufts is accountable to the New England Commission on Higher Education.

“[The grading system at Tufts] seems very similar [to those at other colleges], and I would imagine part of that is due to accreditation processes,” Nathans said. “Transcripts have to be legible across institutions. When you have an external body of accreditors, [such as the New England Commission on Higher Education], they want to see that you are actually evaluating student work in certain ways.”

James Glaser, the dean of the School of Arts and Sciences and a professor of political science, has observed an upward trend in GPA, especially during the pandemic.

“It’s been a slow rise for a long time,” Glaser said. “And then [over] the last couple of years, it’s been quite dramatic, and part of that is — I think — a function of the exceptional pass provision that was put into place because of [COVID-19], which enabled lots of students to opt out of grades that would bring their grade point averages down. … I think that [exceptional pass] was appropriate for the circumstances, … [though] it did have the potential to mask problems that students might have which would lead them less prepared for future classes. That’s the main reason that we … aren’t continuing that policy.”

Jonathan Conroy is a senior majoring in computer science who has served as both a teaching assistant and teaching fellow for Algorithms (CS 160). He noted that he has heard that there have been more regrade requests from students in Algorithms during the pandemic than there had been previously.

“I have only been a TA during [COVID-19], and so I can’t speak to this personally, but I’ve been told that we used to get far fewer regrade requests before the pandemic, even though grading has remained relatively consistent throughout the semesters,” Conroy said.

While Conroy’s anecdote is not evidence of grade inflation, it could be indicative of students’ changing expectations surrounding grades.

Thomas disclosed that members of the administration do not place any specific parameters on the distribution of exact grades, respecting the autonomy of each instructor.

“We have grading policies, but we in the administration don’t go looking [at] how faculty grade individual courses and say, you know, ‘You’ve given too many As’ or something like that,” Thomas said. “I think that falls under this sort of academic freedom.”

Academic performance may be a criterion in college rankings, but Glaser said that this does not exert inflationary pressure on grades at Tufts.

“I don’t think the faculty are thinking about … how each of those individual-level [grading] decisions [add] up to some sort of result at the school or university level,”Glaser said.

From a professor’s point of view, Nathans described the thought process behind grade assignment and how it relates to the progress a student makes throughout the course.

“You look at each student as an individual and you [ask], ‘How far did that person get from wherever they started in meeting the learning objectives?’” Nathans said. “I think if faculty weren’t grading based on student progress, we would literally just hand the test out and say, ‘See you at the final.’”

Thomas elaborated on what grades represent.

“I think it is a very complex set of variables that come together to determine whether someone will be successful or not,” Thomas said. “Are the students who got As in organic chemistry smarter than the students who got Bs? I’m pretty sure I would say ‘no,’ … and I’m not assessing whether those students are smarter.”

Glaser partly related an increase in high grades at Tufts to an increasingly competitive student body.

“I do think that … the large number of very strong students that are at Tufts and other fine institutions … is correlated with high grades,” Glaser said.

Nathans, however, does not view GPA as a great reflection of competency.

“I think GPAs are maybe the least expressive aspect of what Tufts students are,” Nathans said. “I don’t know [if Tufts students] are markedly smarter. I just think [that] the students at Tufts ask fantastic questions and are compelled to do really amazing work in service of those questions. And I think the grades that they may achieve are one manifestation of that.”

The question remains whether grades reflect the level of rigor of a class.

“Are grades [a] measure of rigor? I don't think that they’re the same thing. … They’re somewhat different dimensions,” Glaser said.

Nathans takes issue with the term ‘rigor’ itself.

“The term rigor can be used to close doors rather than open them, … because it can often assume there is only one way of learning,” Nathans said. “And that forecloses … possibilities for people. It becomes a thing that can feel very exclusionary.”

This is particularly relevant to courses that are informally perceived as serving to weed out students.

“I know that there are departments across [the School of Arts and Sciences] that are particularly conscious of this reputation,” Nathans said. “One of the things that I really appreciate hearing faculty talk about [is] … how you reframe [weed out classes] so that they move away from being hazing … to make them as welcoming as possible and to really optimize student success.”

Susan Atkins, the associate director of employer relations at the Career Center, wrote in an email to the Daily that grade inflation can have multiple consequences.

“It’s our understanding that grade inflation creates unequal opportunities for students depending on the employer and their use of grades or transcripts as part of the evaluation process,” Atkins wrote. “Certain industries require a GPA, and of course grade inflation could have a positive impact for some students seeking roles in those particular fields. The downside of grade inflation is that it doesn’t provide students with consistently reliable information about what they do and don’t do well. If someone receives only As and very little in the way of constructive feedback, they might be less prepared for the demands of the ‘real world’.”

Such demands are elucidated by a survey conducted by the Career Center.

“The responses to our survey varied based on industry sector, and we learned that about 53% of our employer respondents don’t require transcripts as part of their overall application process,” Atkins wrote. “We found that about 25% of employers do want to see specific grades as part of their application process vs. seeing a pass/fail or exceptional pass grade. Lastly, about 22% want to see grades and will look at both pass/fail and actual grades equally for students as they are considered for employment.”

According to Conroy, undergraduates generally regard their academic grades through a short-term lens.

“I hear people stressed about the grade they received in and of the grade itself, not necessarily as it relates to some final outcome in the future,” Conroy said.

Going forward, it remains unclear how the overall trend of grade inflation nationwide impacts Tufts and the extent to which it is organic or manufactured.