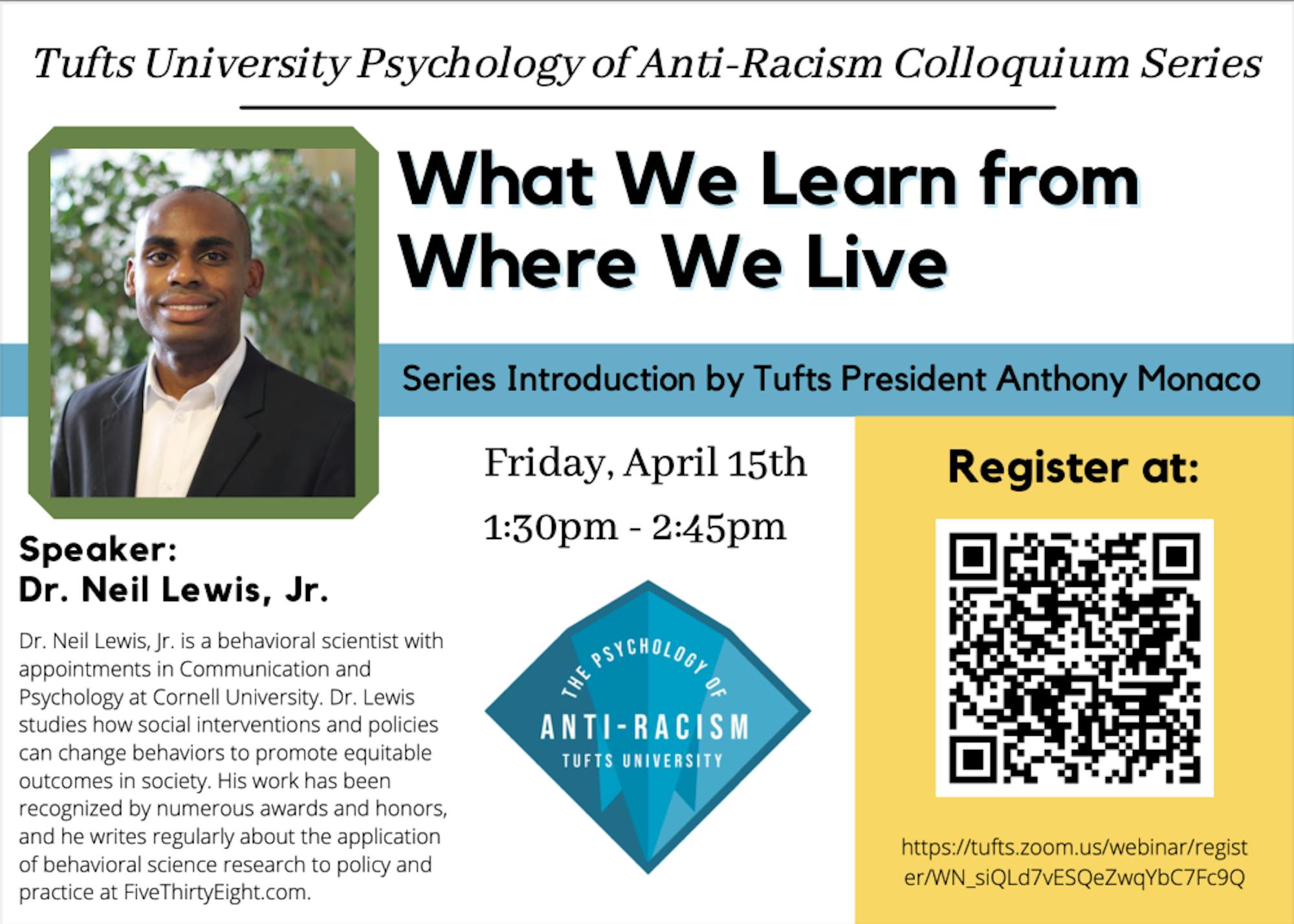

The psychology department hosted its second annual Psychology of Anti-Racism Series talk titled, “What We Learn From Where We Live,” on April 15. The Zoom webinar featured Dr. Neil Lewis Jr., an assistant professor of communication and social behavior at Cornell University, who spoke about how to foster an anti-racist society by understanding the connection between people and the places in which they live.

Professor Sam Sommers, who chairs the psychology department, moderated the webinar. Sommers began by introducing University President Anthony Monaco, who discussed the importance of the event.

“This important event is dedicated to scientific inquiry, which aims to investigate, confront and remediate the causes and consequences of systemic racism in our society and within our communities,”Monaco said.

Monaco went on to talk about the current steps being taken to make Tufts an anti-racist institution and then turned the talk back over to Sommers.

Sommers proceeded to introduce Lewis, who, in addition to his position at Cornell, has an appointment as an assistant professor of communication research in medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine.

“Dr. Lewis’ research examines how the interplay between people’s identities and social contexts influence people’s motivation to pursue their goals and their success in goal pursuit efforts,” Sommers said. “He most often studies these processes in the domains of education, health and environmental sustainability in hopes that a better understanding of situated, identity-based motivation processes can provide useful insights for developing interventions to help people achieve their goals.”

In an interview with the Daily, Lewis spoke about why his talk is important for the Tufts community.

“Tufts is one of many universities … that has been really doing some soul searching and reflecting on what both individuals can do and what can larger institutions do, to move towards more equity and justice in our society,” he said. “There’s lots of things that Tufts is trying to do, and I think this talk could help the Tufts community have some better understanding of some of the science behind these other initiatives that are happening.”

During his talk, Lewis discussed how societal stratification affects how we think about the American education system and how it creates barriers and disparities.

“In effect, by segregating our society, the law has created two different pathways,” he said. “There are some students for whom there’s a clear shot from the cradle to college and other students for whom we’ve made it a long and winding road.”

Lewis talked about some of the steps that can be taken to improve the barriers to matriculation in the American education system.

“One of the things we’ve done … is build programs into the fabric of institutions that take these issues seriously, and then use the insights to change the experiences that students have and the resulting outcomes from those experiences,” Lewis said.

Next, Lewis talked about the stratification processes in the American legal system and specifically how these processes can affect jury decision making about police brutality.

“With little information to go on, juries often have to rely on their priors, [which] … depend on how you grew up and were socialized and the experiences you had in those contexts,” Lewis said. “These jurors who were drawn from the segregated and stratified society are starting from different places, and they’re thinking about officers due to those differences in past experiences.”

Lewis and his colleagues found that the language used in court appears to be shifting judgments to the favor of officers rather than respondents.

Finally, Lewis spoke about environmental injustices and how the field of psychology hasn’t paid enough attention to the people who are most adversely affected by environmental issues.

Lewis pointed to a poll he conducted where he found that “the highest levels of environmental concern in the [United States] are among racial minorities and poor people. … That makes sense, given how the patterns of segregation and stratification … have led to those groups having higher exposure to environmental hazards than their whiter and wealthier peers.”

Lewis said that the field of psychology needs to improve representation in study samples. One of the ways that he and his colleagues are doing this is by building on community partnerships to recruit participants from underrepresented groups. In turn, this has shown them how much race and class segregation in the places where people live have shaped how Americans receive and conceptualize environmental issues.

“What I now think of as one of the biggest collective action problems facing humanity, [is] if we don’t take the time to figure out what people are experiencing and learning from the places where they’re living, it will be difficult to build the kinds of coalitions that are necessary to get out of the mess that we’re currently in,” he said.

Lewisconcluded that in order to solve this problem, individuals must actively work to change the places where they live and the institutions they inhabit.

“If we do that, … we will not only be better positioned to make meaningful progress, we’re building an anti-racist society,” Lewis said.