When you think of where your meat comes from, you’re probably thinking of a farm. But here on campus, a group of scientists is creating meat.

The cellular agriculture research team at the Kaplan Laboratory focuses on "the basic science that underlies cultured [and] in vitro meat," which means the generation of muscle and fat tissue outside an animal’s body. This is otherwise known as cellular agriculture. According to the website for a course affiliated with the lab, some of their target points include "muscle cell engineering to enhance nutrition and cost reduction," the use of insect cells for large-scale meat tissue generation and the "application [and] adaptation of conventional meat science techniques to evaluate meat generated in vitro."

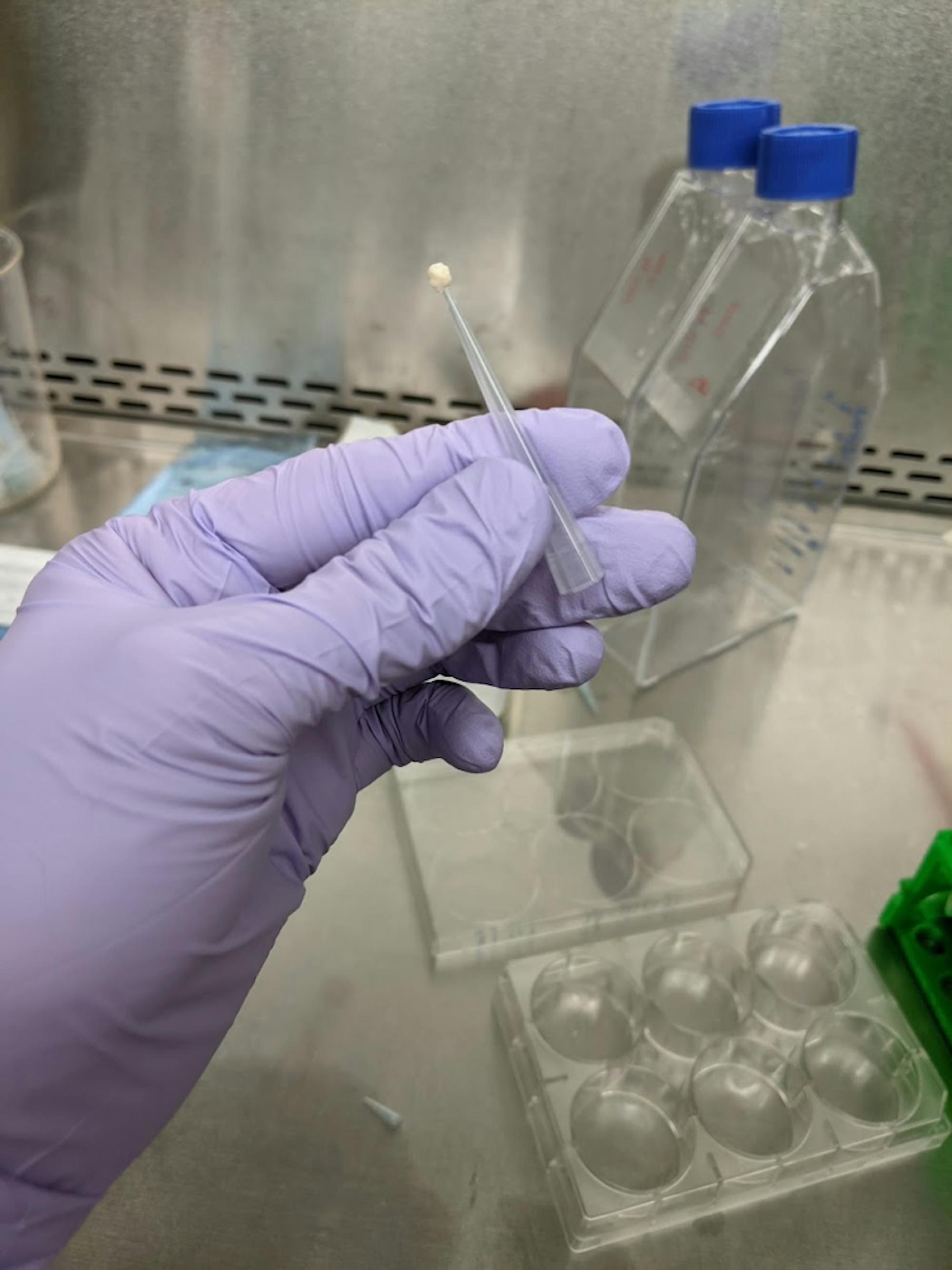

“What we do, essentially ... is that we isolate stem cells from tissue, for example from a cow,” John Yuen, a Ph.D. student who works in the Kaplan Lab, said. “And then we try and multiply those stem cells, proliferate them into a huge amount, and then turn those little cells into actual muscle fibers.”

Cells in the body have two stages: the first is the proliferation phase where cells multiply, and the second is the differentiation phase, where cells stop dividing and form different cells, leading to function-specific tissues and organs. The cells then mass-produce the proteins required for the contraction function of the muscle, differentiating into muscle fibers, a process researchers aim to host in their Petri dishes. The animal-derived tissue can either come via a biopsy or a sample from a slaughterhouse.

The Kaplan Lab has been using primarily bovine samples from Tufts’ Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, as cows have the largest negative environmental impact of livestock grown for human consumption. In general, livestock alone makes up around 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and the food industry as a whole accounts for a third of our carbon emissions. While cows have a serious environmental impact, Yuen is interested in fish for both environmental and human health reasons. In terms of the environment, overfishing decreases biodiversity, and on the human side, mercury via biomagnification has been an increasing health concern due to toxicities.

When it comes to cellular agriculture, however, one may wonder if the energy used to cellularly grow meat equals that of traditional agricultural practices. There are many life cycle analyses on cultured meat, which are all speculative at the moment.

“It usually comes down to [that] cultured meat [has] a lot less land use and eutrophication because you don't have the pollutants just running off into the waterways,” Yuen said.

Proponents of cellular agriculture believe that it could reduce land, water and chemical inputs and minimize greenhouse gas emissions. In contrast, points of high energy may come from using a bioreactor, a machine used to manufacture cellularly grown meat on a larger scale. Because the scale of their production is much smaller than any potentially commercially available solution, the Kaplan Lab uses Petri dishes.

“If we're doing a little experiment to investigate one small aspect of how the cell works … all we need is just a test because we just need a little bit,” Yuen said.

On the economic side, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics lists the December 2021 average price of ground chuck beef across U.S. cities as $4.79 per pound. While the members of Kaplan Lab are not scaling and producing the meat themselves, some companies are gearing towards industrial meat-producing scales. In fact, even some of the biggest conventional meat producers like Tyson and Cargill are becoming involved in the cellular agriculture space.

However, there is controversy in the field as to whether cellularly grown meat can become cheap or whether it will never be able to be done cost-effectively. Some believe cellularly grown meat can be produced at the same cost as conventional meat once it has scaled up. The first slaughter-free hamburger based on laboratory-cultured meat was unveiled in 2013 by the CSO of Mosa Meat, professor Mark Post, which cost $280,000. The scaling is a challenge due to the growth pattern of the animal cells attached to surfaces.

Sean Cash is an associate professor at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy who works closely with the Kaplan Lab to assess the interaction of economics and cellular agriculture. He has been analyzing barriers to consumer acceptance, how cellular agriculture will be regulated and what to call it.

“This is really a story of [figuring] out how to do things, but the real challenge is making it bigger,” Cash said. “If you think of what the early precursors of cellular [agriculture] work [were], it's been in using animal cells for medical purposes ... but those would never require the types of scales that you're talking about for food production.”

Another barrier is more linguistic in nature. There is a current debate as to whether cellularly grown meat should be called “meat” to begin with.

“If you’re a conventional beef producer, you want cellular products to not be able [to be called] 'beef.' You want them to have to use different things to put them in a high-tech food box,” Cash said. “If you’re a member of this nascent industry, you want to be able to have the freedom to use whatever phrases you think will help you most connect with your future, potential consumers.”

In 2018, the U.S. Cattlemen’s Association sent a petition to the USDA that they summarized as saying: “The terms ‘beef’ and ‘meat’ should be retained exclusively for products derived from the flesh of a [bovine] animal, harvested in the traditional manner.” Based on the comments received, the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service found that while most opposed the petition, nearly all agreed that cultured meat should be labeled to identify its method of production.

According to a study from Penn State, the development of cellular agriculture may increase socioeconomic inequality by concentrating power in the food system and displacing farmers and fishermen who are already struggling. The same study also found that it could lead to great improvement in sustainability for the food industry.

“Creative destruction ... is always a part of new technologies, and displacement of existing workers and industry sectors is a separate issue from market concentration because displacement of farmers and fishermen is already happening,” Cash said.

Cash believes that if cellular agriculture takes flight, new people will be hired in this space, as has happened in the past with new innovations.

As for market concentration, Cash acknowledges that increased reliance on technology and patented information could further concentrate power on the economic scale and intellectual property side. Regardless, Cash is a proponent of maintaining research in the public space. Recently, the Kaplan Lab received $10 million in funding from a USDA grant to optimize its cellular agriculture efforts. In particular, the grant will allow Tufts to create the new National Institute for Cellular Agriculture, the first government-funded protein research center.

“One of the best ways ... to make sure that new technologies can be forces for diversification and democratization of access to production, and maybe help us deconcentrate some of these things ... is to have the key technologies live in the public sphere,” Cash said. “If these advances happen ... only in the hands of private companies, or if they happen in government labs in other countries where there might be closer coordination with the industrial sectors, then that’ll just lead towards market concentration.”

To embrace inclusivity, according to Cash, technologies should lie in the public sphere, existing in a system of peer-reviewed research and publicly accessible patents. Onboard with these values, New Harvest is a nonprofit organization aiming to maximize the positive impact of cellular agriculture.

“We foster technical leadership, build scientific infrastructure, and address knowledge gaps in cellular agriculture,” Meera Zassenhaus, Communications and Media Manager at New Harvest, wrote in an email. “In the long term, we work to ensure this burgeoning industry delivers on its promises to reduce our dependence on animal agriculture and the heavy toll of meat production on the environment, animal welfare, and public health.”

She hopes that cellularly grown meat will eventually replace factory farms, with the ability to buy cell-cultured crunch wraps at a local Taco Bell in the future. Cash shared the possibility of seeing a mixture of cellularly grown meat and conventional meat in one product as well.

Overall, as Zassenhaus wrote, one thing is clear: “We need a pipeline of talent, data, and expertise coming [from] universities. That’s where the most experimental, cutting edge research happens anyway.”