A decade ago, following in the footsteps of its Tunisian neighbor, Libya revolted against the decades-long dictatorship of Muammar Gadhafi. The self-proclaimed “king of kings” of Africa responded in a typically bloody fashion by firing on demonstrators and imposing harsh repression. Bolstered by its European allies, notably Nicolas Sarkozy’s France, the U.S. assembled a wide-reaching NATO operation in support of the rebellion. The UN declared Libya a total no-fly zone, and months of round-the-clock aerial bombings quickly tilted the advantage into the rebellion’s hands. Gadhafi’s Jamahiriya (which, ironically, translates to “state of the masses”) fell in late 2011, and the dictator was captured and killed in October of that year.

Widespread chaos quickly followed. The coalition had misjudged the new UN-backed National Transitional Council’s ability to govern the unstable country. Libya descended into a full-blown civil war that split the country into a UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) in the west and an east backed by multiple U.S. allies, notably Egypt and the United Arab Emirates. In a confusing turn of events, traditional allies gave their backing to the side opposed to the United States, with France and Saudi Arabia notably opposing the GNA. In April 2019, the eastern Libyan National Army, led by General Khalifa Haftar, launched an offensive on Tripoli that aimed to forcefully reunify the country and crush the GNA.

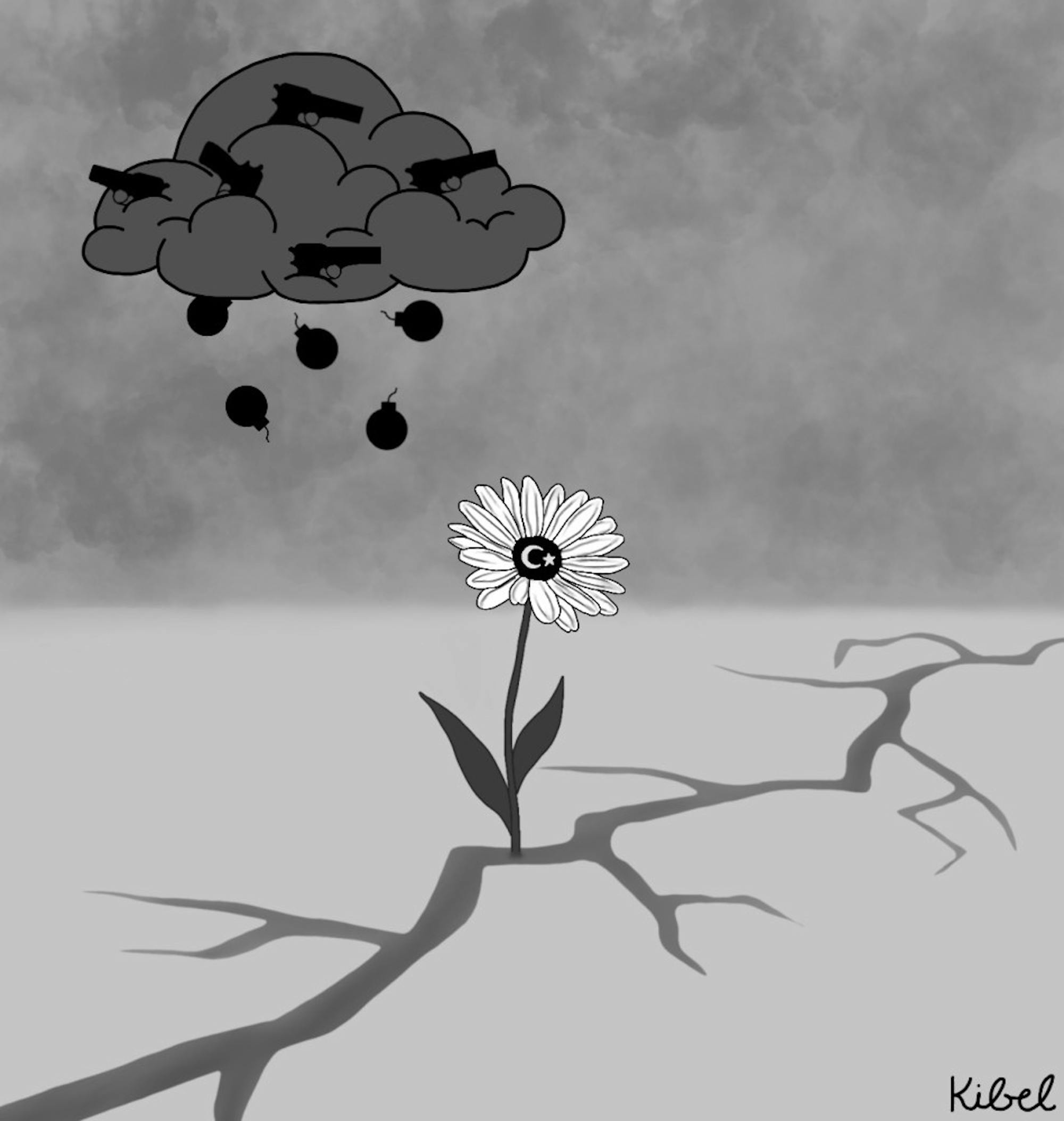

Haftar advanced rapidly and scored many victories, compelling the GNA to sign an agreement with Turkey for military cooperation. Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan quickly sent in tactical support that controversially included mercenaries recruited in war-torn Syriato fight on the Libyan stage for meager salaries. The Turkish leader’s decision was an attempt at carving out for himself a position as a regional power broker.

Libya’s strategic location and valuable contribution to Europe’s energy supply make it highly prone to interference from many countries. It is a phenomenally hydrocarbon-rich nation and has long been one of Italy’s main energy suppliers. Furthermore, its location in Northern Africa, with an extensive coast on the Mediterranean, could make it a vital logistics hub for establishing naval bases. Libya's strategic position between many regional powers also makes it a prime location for movements to curb its neighbors’ influence.

Indeed, the Arab League already feels Iran's pressure in its eastern regions, and Turkey has played the same trick on the Mediterranean Basin. A proxy scuffle between Libya’s Arab neighbors and this newcomer, Turkey, emerged. As mass graves were discovered in GNA-reclaimed areas, Egypt’s President threatened a full-blown intervention if the Turkey-backed GNA advanced on the city of Sirte. The opposing sides fell back to an east-west stalemate, and the UN quickly acted to organize peace talks in Geneva. The effort succeeded.

In October 2020, the rival administrations signed a ceasefire agreement that paved the way for the upcoming elections. While the UN is often criticized for seldom achieving good results, this success can be attributed to Western powers’ explicit desire to curb Turkish influence and prevent Egyptian bulwarking of itsNorth African borders. The West is also seemingly attracted by the myriad investment opportunities that may open up once Libya stabilizes, eager to nudge away any competition.

The December polls will be the Arab country’s first direct presidential election since 1951.Turnout is assumed to be accordingly enthusiastic, with the population finally seizing this opportunity to enact change after its revolution was stolen from it by warring militias.

One surname on the list of potential candidates sounds quite familiar: Gadhafi. Indeed, Saif al-Islam — longtime heir apparent to his father — hinted at a presidential bid in a surprisingly comprehensive New York Times interview. Saif had, in years past, adopted a posture similar to that of Syria’s Bashar al-Assad toward his father Hafez. Saif sold himself as a reformist who would eventually take over and bring Libya into the modern age. However, it wasn’t to be, as he stands accused of a long list of war crimes.

It is a testament to the instability that hit Libya after thesenior Gadhafi’s death that a significant portion of the population wants a return to the family. This observation in many ways parallels the Iraq war. After a U.S.-led coalition toppled Saddam Hussein’s regime and wiped out Iraq’s army, angry Iraqi generals built their private militias and waged war throughout the country. Without its strongman, the nation was quickly overrun by Iran's influence, deeply harming the peace process and throwing Iraq into permanent turmoil.

In Libya, it was again a U.S.-led NATO coalition that left the country prey to interference. Gadhafi was no doubt a bloody dictator, but removing him laid bare the entire state apparatus. Military men took advantage of the chaos, claiming entire chunks of the country’s institutions. Corruption became rife, and instability set in.

Going to war abroad and flaunting democracy does not work without a deep knowledge of the country in which you are fighting and a serious plan involving local actors to replace the dysfunctional system. Militias might be good at engaging in battle, but they are not necessarily ready to run a country, especially one like Libya, which has an extremely fraught and fragile relationship with democracy. The United States is getting involved in too many wars and then withdrawing with her work unfinished, leaving countries in worse shape than they were initially, and with the same exactions and corruption still rampant. It is now time for the U.S. to exercise restraint and carefully consider the battlefield before demolishing a dam, however flawed it may have been.